Catherine Opie and Self-Portraits

Why does the American fine art photographer regard pictures of herself as her only definitive proclamations?

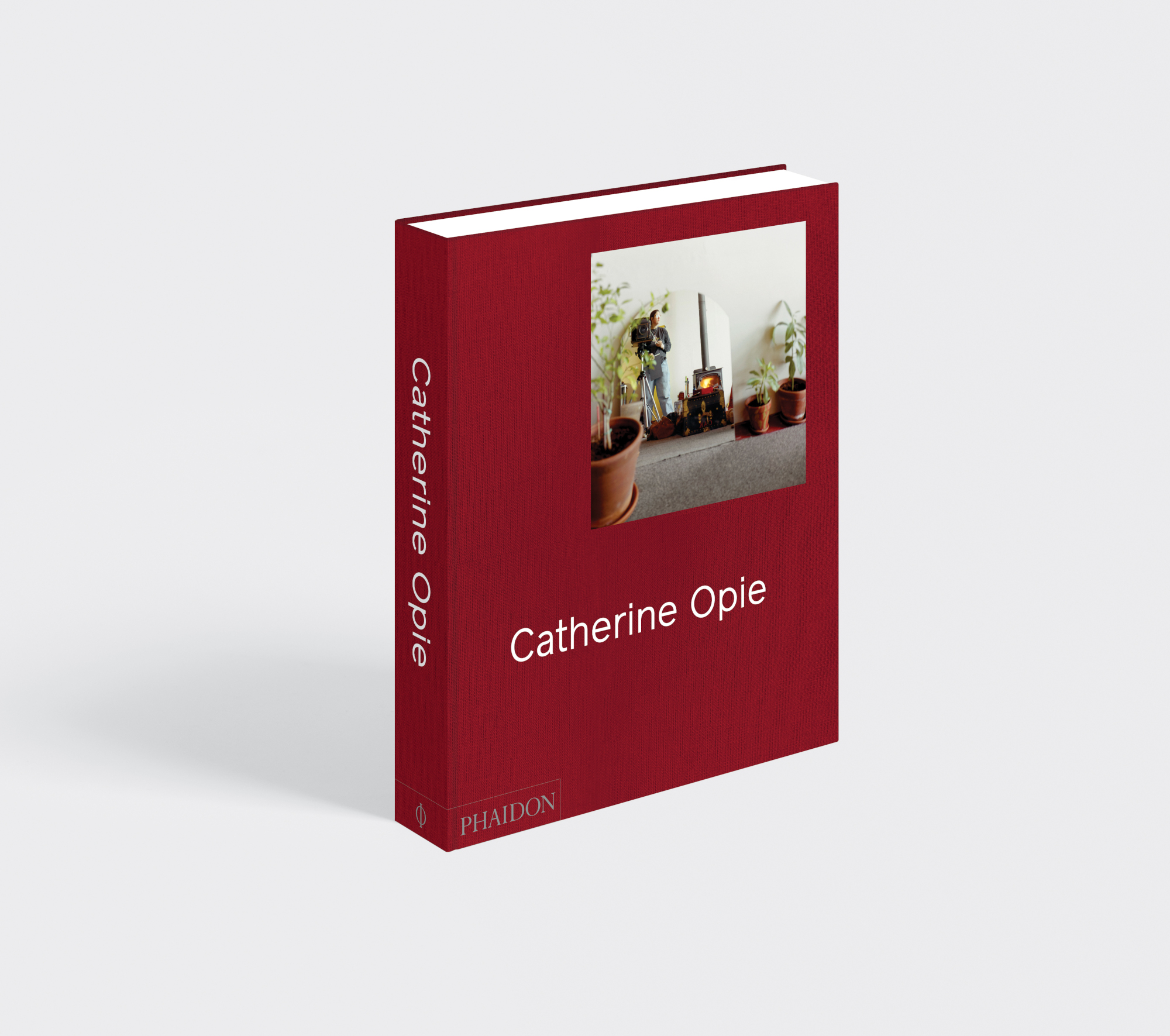

Catherine Opie got her first camera at the age of nine, “after doing a school report on early twentieth-century photographer Lewis Hine and his portraits of child laborers,” explains the writer, curator and executive director of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Elizabeth A. T. Smith, in our new book, the first survey of the work of one of America's foremost contemporary photographers.

A few of Opie’s own early pictures included one young person in particular: Opie herself. Our long-awaited monograph, reproduces these early images; there’s Opie as a kid, pulling muscle-man poses from 1970, a shot of her in a sophisticated hat and long coat, in New York in 1985, and, of course, many, later images that sit alongside Opie’s famous shots of football players, leather-bar regulars, surfers, friends and landscapes.

The fine-art photographer made a name for herself with her self-portraits, gaining fame, and infamy, for one couple in particular. As Smith explains, when her images Self-Portrait/Cutting and a related work, Self-Portrait/Pervert, were first shown at the 1995 Whitney Biennial new New York, the images “introduced Opie’s work to the broader art world.”

These images were read as profoundly political and decidedly brave in the way the artist used her own body to foreground issues of sexuality and marginalization, immediately eliciting a range of critical and theoretical discourse. Self-Portrait/Pervert was an especially adamant statement of Opie’s belief in challenging the invisibility of the S/M subculture, an aim embodied by a series of portraits of her friends in the leather community in San Francisco and Los Angeles.”

Opie herself more or less acknowledges this in the Q&A section of our new book, telling British writer and curator Charlotte Cotton about the sexual and social politics that produced those works. “I have had friends lose their jobs. I’ve had friends die, and their relatives come in and take all of their lover’s belongings and all of their money, leaving them destitute,” the artist says. “So when I made Self-Portrait/Cutting and Self-Portrait/Pervert in 1993 and 1994, my thinking was, ‘Well, fuck it.’ I had to make work that I believed in politically. I had to get rid of my Republican Ohio parents’ voices saying, ‘You’re not going to be able to get a job’ or whatever. And it required me to do another coming out to my parents. They knew I was a lesbian, but they didn’t know about my other practices within the community. It was definitely a huge risk making that work, but it was a risk I had to take.”

We can’t show you those images, but they are reproduced in our book, and they are pretty shocking. The author and curator Helen Molesworth describes Self-Portrait/Pervert in our new book: “her face covered by a dastardly comprehensive black-vinyl hood; running up both arms, like an exoskeleton, were two perfectly placed lines of symmetrical needles puncturing her skin. The finishing flourish, the word pervert floridly cut into her decolletage—her skin red and inflamed, the blood still bright red. The picture scared the shit out of me. If I’m honest, it still does.”

And yet, the pictures remain beautiful too, as Opie admits. “I think that’s what confused the shit out of people: ‘I know that I’m supposed to be really upset about this, but, boy, that’s beautiful.' “I knew I had to use aesthetics to talk about my community at that point in time, that there needed to be a different way to enter it beyond a documentary style. I was still documenting, but there’s a formality there. I was asking people to take seriously what was happening in my own community.”

Elsewhere in the interview, she describes her self-portraits as “the only definite proclamations I have made.” Of course, as the years have gone by, Opie has found different things to proclaim about herself. Self-Portrait/Nursing, from 2004, shows how a leather-bar regular can become a mother; look closely at this frank portrait and you can still see where Opie carved ‘Pervert’ into her chest. Self-Portrait/Chopping, from 2011, meanwhile, shows a strong, outdoorsy woman in her middle age, showing off her physical prowess in a way not so dissimilar to the much younger girl from the 1970s, flexing her biceps. There’s humour there, beauty, and risk too. And, in every case, a risk worth taking.

To see all the images discussed as and much more, order a copy of our Catherine Opie book here.