The struggle for NASA's moon photographs

51 years on from Apollo 11's moon landing, we look at how those now iconic photos of the moon reached their audience

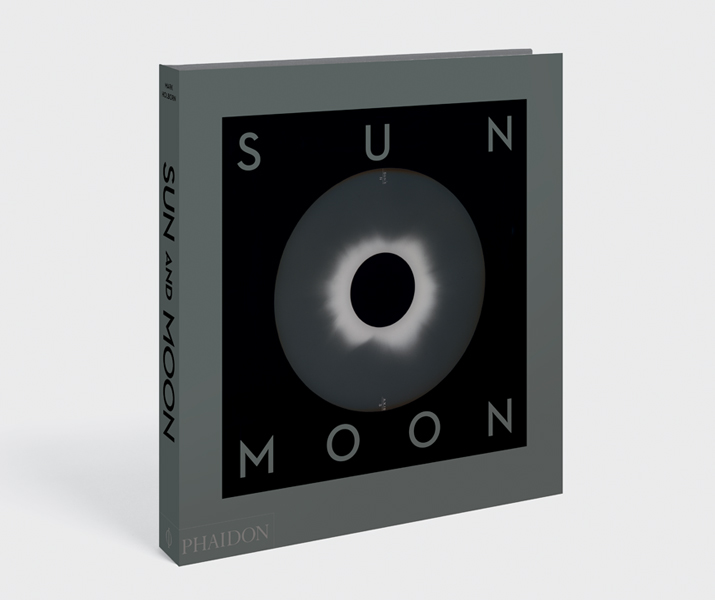

For all but a select few of us, humankind’s trips into space have been experienced at one remove. So space exploration is, for almost all of us, a photographic experience as Mark Holborn suggests in his book Sun and Moon: A Story of Astronomy, Photography and Cartography.

The history of the Apollo missions, beginning with the doomed Apollo 1 in January 1967, in which the crew – including Edward White – died in a fire during a test, through to the triumph of the first Moon landing by Apollo 11, 51 years ago today (July 20), and culminating with the sixth and final Moon landing by Apollo 17 in December 1972, can be regarded as a "collective odyssey executed before the camera lens,” writes Holborn in Sun and Moon.

Yet, beyond a few familiar images, pictures taken through that camera lens weren’t largely shot for public consumption. As Holborn explains in his book, much of the planning and execution of the moon missions was carried out with the aid of advanced photography.

“100,000 photographs were made in order to establish the best possible landing sites,” he writes. “The first lunar probe, Ranger 7, crashed into the lunar surface in 1964, but even as it was plunging it successfully sent back photographs. In 1966, probes were signalling back pictures of the Moon’s surface as if seen at astronaut height.”

“A methodical mapping of both sides of the Moon was carried out by lunar orbiters that carried automatic film processing and scanning equipment in order to radio-transmit the images back to Ground Control in Houston. The programme was managed by the Langley Research Center, with Boeing as its main contractor and the Radio Corporation of America and Eastman Kodak as subcontractors,” Holborn goes on to say. “Kodak produced special high-definition aerial film for the purpose, with which the photographic and cartographic survey was completed. By 1971, NASA had created the Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon.”

While the world’s press reproduced a handful of other, now well-known images, other pictures from the moon missions remained filed away and inaccessible until the late 1990s, until the Californian artist Michael Light began petitioning for their release.

“Of the 32,000 photographs made during the entirety of the Apollo missions, Light persuaded NASA to release 900 of the ‘master’ negatives and transparencies,” Holborn writes. “The ‘masters’ were, in fact, first generation copies, since the actual originals were permanently archived. The so-called ‘masters’ were as close to the original as anyone could handle. Light began a methodical examination and scanning of the key pictures in California in the late 1990s, conducting this work on the cusp of the digital age with astonishing results.

“Eventually, by stitching together frames, he was able to produce wall-size panoramic images of the lunar surface with unsurpassed clarity,” Holborn writes. “His goal, however, was not a series of spectacular moonscape prints, but the construction of a three-part narrative, drawn from pictures made throughout the entire program and including images of the space walk from Gemini 4.”

Light’s chief ambition wasn’t astronomical; he sought to present the images as part of a landscape tradition, and also perhaps remind us of our place in the wider universe.

“He turned the focus, derived from hours of scrutiny of the tiniest detail of the lunar scene, to the Earth. The journey outside our realm, he emphasized, only led us back to regard with greater clarity the point from which we started. ‘The Apollo missions have annihilated the last shreds of expansionist mythology: the concept that Earth can continue to offer people and nations infinite resources, that progress implies a liberation from responsibility, or that we can truthfully call anywhere else home.’”

Those earthly limitations are all the more apparent now, 50 years on from that first moon landing, and two decades on from Light’s recovery of the images.

To read more about how image making has shaped life back on the ground, get a copy of Sun and Moon here.