Should we look at deep space images as works of art?

The Hubble Telescope's photos are as mediated as anything created by a contemporary artist writes Mark Holborn

The reason for launching the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit back in 1990 was well understood, not only within the astronomical community, but also among the wider public.

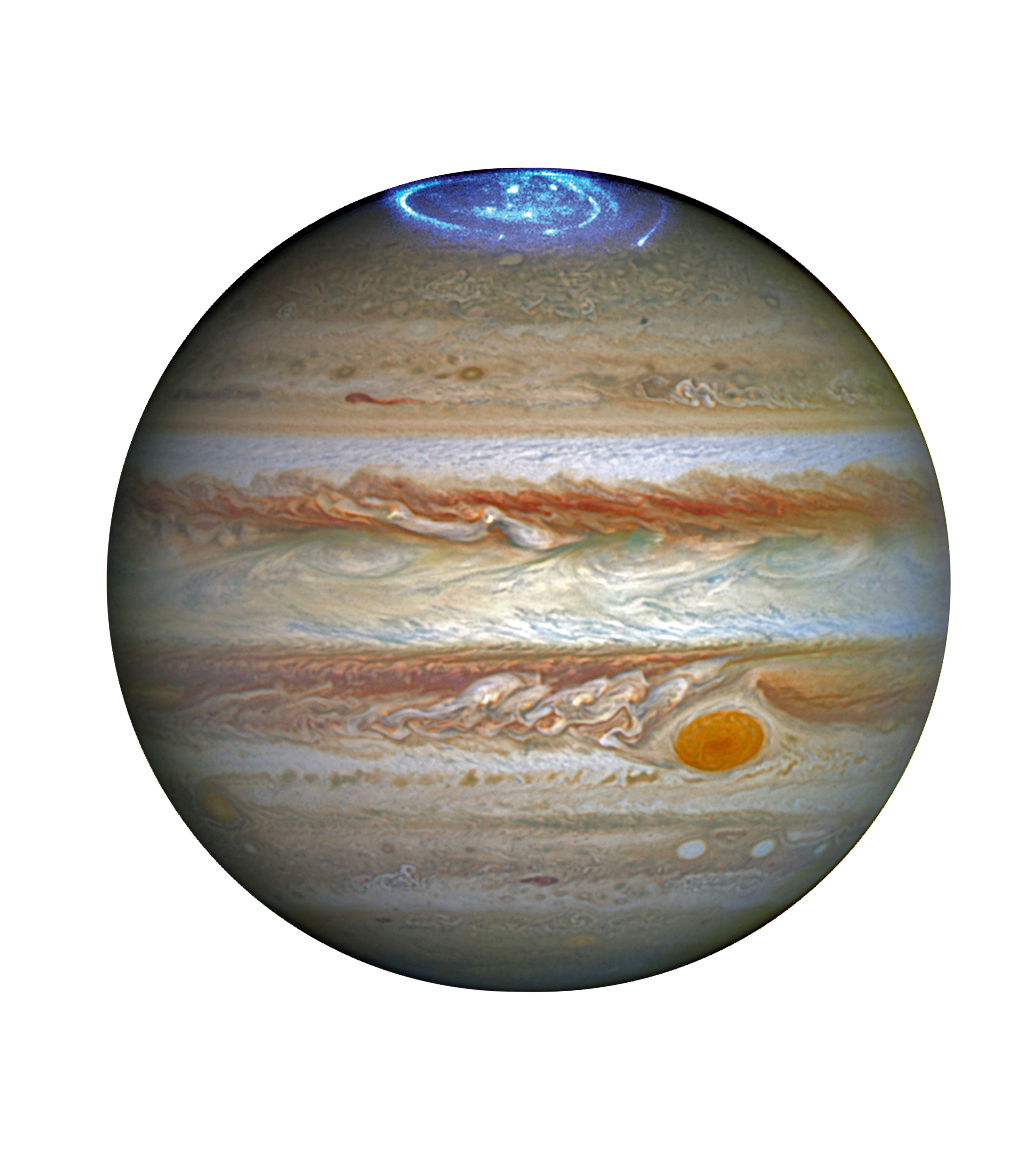

“From its position outside the Earth’s atmosphere, the telescope can absorb the shorter wavelengths of near ultraviolet and the longer wavelengths of near infrared light that lie on the cusp of the visible spectrum,” writes Mark Holborn in his book on photography, astronomy and cartography, Sun and Moon.

“The eventual high-resolution imagery it produced confirmed all that Hermann Oberth [an early 20th century proponent of a space telescope] had suggested about the possibility of a greater clarity when liberated from atmospheric distortion.”

What was less clear was what should be done with the pictures, once they were beamed back to earth. As Holborn explains, “the pictures were products of a digital age and were disseminated online with an impact that Oberth, with all his prophetic genius, could not have foreseen.”

The pictures were never simple, impartial representations; they always contained some element of human intervention. “The photographs were subject to digital manipulation, but regardless of the sophistication of the software, decisions about adjustments to enhance the clarity, notably the use of colour in order to render the visual data more legible, were human choices,” argues Holborn. “This scientifically derived information was as mediated as any image emanating from the studio of a contemporary artist, if not considerably more so. The photographs, unsurpassed in their range and detail, would in some cases become part of an almost universal visual vocabulary.

“They were regularly uploaded, to be freely observed by anyone with internet access. The Hubble digital image became an instrument with which to stir the public imagination as much as to impart data, for public support was essential for continued funding.”

However, Holborn argues that the popular appeal of Hubble’s incredible deep space imagery actually undermined its funding.

“Investment in the enterprise was, ultimately, a political decision,” he writes. “After the disintegration of the Columbia shuttle in 2003, a fifth mission to upgrade Hubble was cancelled. Its reinstatement may have been, in part, due to political lobbying fuelled by the impact of the photographs. Hubble has become a public facility to the extent that its use, funded by the US taxpayer, is openly available; thousands of applications are made annually, of which some 200 are successful.

“Through this process, a technological facility has become part of the democratic fabric, and as such it possesses an institutional function. This eye in space operates, ultimately, under the control of those who administer allocated budgets.”

And, as Holborn points out, the space telescope’s open-ended brief was quite unlike early space projects, placing it at an additional disadavantage.

“When Kennedy originally declared his space mission in 1962, its purpose was established. The race, however monumental an endeavour, was simple in its stated ambition. Hubble, despite the magnificence of its results, is less defined. The breadth of the vision comes at the expense of a singularity of intention. In some of the imagery, sheer drama was in danger of appearing to override scientific purpose. Drama in the public sphere has a particular contemporary currency, of course.

“The science fiction narrative, the serial movie franchise, the greater and greater resolution of the digital world leading to the Imax screen and revived 3D effects, all reveal an unending hunger for the spectacular.”

It’s a pity that this popular appeal may have undermined Hubble’s funding, as you can see its artistic influence is certainly wide reaching. You only have to sit through the space travel scenes in the new blockbuster Avengers: End Game, to see how Hubble’s colourful, gaseous images of space have changed the look of interstellar travel in the movies. And, while we might not able able to hang a Hubble image beside a Picasso and claim absolute artistic parity, the sublime side of its pictures places it in a unique place, both astronomically and artistically.

“The visual language of the Hubble photographs conformed to the established convention, rooted deep in the wider consciousness, of luminosity, which elevated the imagery beyond the realm of neutral, secular data,” writes Holborn. “Counter to the notion of a diminished function as a mere source of spectacle, the subject matter on which the Hubble fixed its eye was galactic in scale; it could take the viewer to a territory of star birth or star death, and in so doing accommodate the grand scheme of a mutable universe at its most profound. The Hubble imagery could simultaneously cross several domains – the Sublime, the spectacular and hard, scientific enquiry. The Hubble view of the Eagle Nebula, M 16 (Messier 16) [top], from 1995 achieved exactly that.”

We might not all look at that picture, at the top of this article, and identify it as an actively star-forming gaseous region 7,000 light years from Earth in the constellation Serpens; yet we can all agree that it looks pretty awesome, and as enjoyable to view as many, highly successful – and equally manipulated – works of art.

For more on the earthly story behind heavenly image making, order a copy of Sun and Moon here.