ICP curator Charlotte Cotton talks Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin and new show Public, Private, Secret

We can all get a little camera shy from time to time, and we all probably appreciate how social media has sharpened our appreciation of personal representation. But how does all this self portraiture fit into the greater history of the photographic medium?

The International Center for Photography opens its new exhibition space at 250 Bowery in Manhattan today with an inaugural exhibition, Public, Private Secret, dedicated to the shifting place of those personal realms within image production. To mark the event, we spoke with the ICP’s new curator-in-residence, Charlotte Cotton, about the age-old photographic drive of voyeurism, and how it's giving way to social media’s newfound thrills of exhibitionism.

Where did the idea for this exhibition come from? It goes back to the founding ideas for this new space at 250 Bowery, where ICP will host a head-on discussion about the most important issues in visual culture and society. It looks at how the boundaries between our public, private and secret selves are being changed by photography.

How do you examine those ideas? In two distinct spaces. The first room you go into is all about your own image. You’re surrounded by mirrors; the lighting makes it clear that you are the subject; and there are two CCTV cameras trained on this section. You are at the centre of things.

Then, in the second gallery, you’re encouraged to consider how a series of different pictures connect. There’s a Cindy Sherman image next to a Kim Kardashian book of selfies, next to an Andy Warhol Polaroid, next to a new range of work by younger artists influenced by mass celebrity online. The onus is on the viewer to shape the meaning of all this.

Was the show’s curation quite a personal experience for you too? Yes, it was for all of us who worked on it. The show is immediately personal. You can’t think about voyeurism in a detached way - it immediately calls on your own values and memories.

The earliest pictures in the show date from the 19th century. How has photography’s relationship with publicity and privacy changed over that time? Voyeurism is strong in photography throughout the 19th and 20th century, but with the arrival of social media, exhibitionism comes in. That’s the other side of it; we’re are in the land of the selfie. That’s at the heart of the show.

It’s easy to see the beauty in a Warhol Polaroid or a Nan Goldin photo, but perhaps harder to appreciate the worth of a series of Instagram shots. Where does the beauty lie in the social media pictures? I’m not sure, because, to our eyes, the aesthetic is so neutral, so everyday. However, beauty and aesthetics aren't really in the top line of this show. We’re not asking you to look at Warhol’s Polaroids as beautiful objects, even though they are, but instead to look at what he’s doing, how he is creating celebrity.

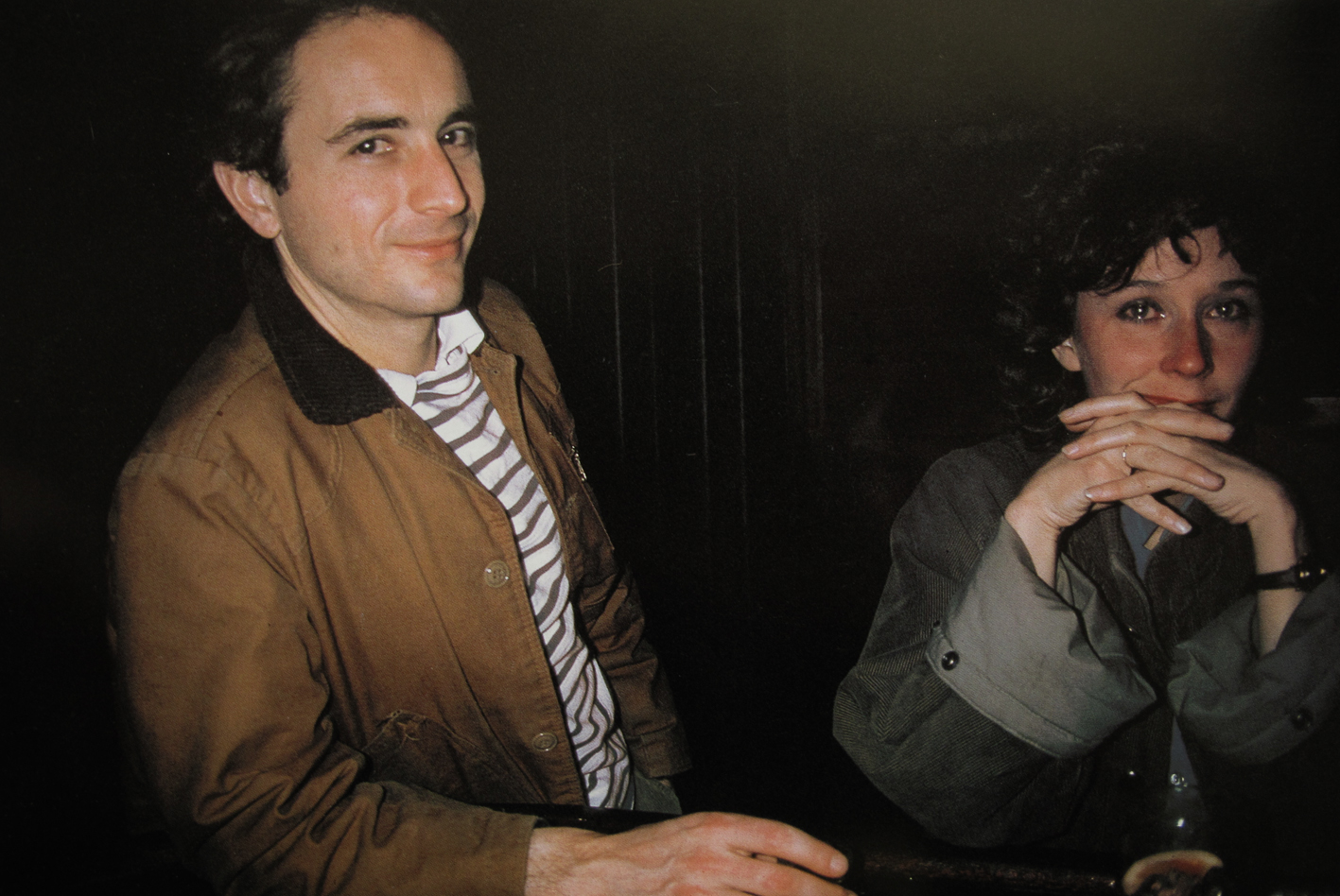

Which Nan Goldin photograph have you chosen for the show? My all-time favourite one! It’s called David With Butch Crying. I just love this photograph. It’s of a man and woman in a bar, and the woman’s eyes are brimming over with tears. It’s so Nan Goldlin. On the one hand, it’s just a picture of her friends kind of smiling at the camera - just a social, Instamatic picture. On the other hand, she just caught this moment in a way she does. It’s the brilliant way she brought reality and intimacy into contemporary photography. It was important to have her in the show.

How about the Cindy Sherman inclusion? We have just one untitled film still. She’s dressed up like a 1920s Hollywood starlet wearing a platinum wig and the camera is in the bushes, it’s like a paparazzi image. It’s on the same wall as a [leading 20th century paparazzi] Ron Galella’s photograph of Jackie Onassis, where she’s running away from his camera. It’s a historical representation of a celebrity and the media.

At the time Galella was seen as quite a toxic influence on photography, but today his paparrazi style looks quite tame, doesn't it? Yes. The New York Post called Jackie O and Ron’s relationship the most co-dependent celeb-paparazzi ever! Today you can reach an audience without resorting to tabloids, as Kim Kardashian has proven. Today paparazzi look quaint in a way. It was always a very obvious and clear transaction.

Public, Private, Secret is on at the International Center for Photography until 8 January 2017. For more on Nan Goldin take a look at these books; for more on Cindy Sherman consider this overview; and for more on Warhol take your pick from these beauties.