The photos that spread Martin Luther King's message

On Martin Luther King Day we look back at two powerful images from the 20th Century Civil Rights movement

Martin Luther King may have led the USA’s Civil Rights Movement from the early 1950s up until his death in 1968, yet he and his fellow activists eventually succeeded, not only due to Dr. King’s incredible determination and oratory skills, but also to some like-minded image makers, whose pictures both chronicled and helped King's noble campaign.

Consider this early one below, from 1957, shot by the US press photographer Douglas Martin and reproduced in The Photography Book. It was taken only two years after Dr. King began his campaigning, leading the boycott of the segregated bus service in Montgomery, Alabama, and it captures the movement’s early, peaceful years.

“The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., then a minister in Montgomery, became the leader of the movement, and was unchallenged until 1960,” writes the art historian Ian Jeffrey, “when his commitment to non-violence was questioned by a new generation of activists. This image commemorates that early era of passive resistance.”

Photographs such as this one not only documented the changes, but also acted as a kind of visual campaign tool, as Jeffrey explains. “In part the change came about because of the distribution of such pictures in which defenders of the old injustices presented themselves as self-confident bigots. Dorothy’s two civic escorts, one scarcely older than her tormentors, seem like two halves of the American psyche, caught somewhere between a reluctant admiration and a grim determination to carry out an unpalatable duty.”

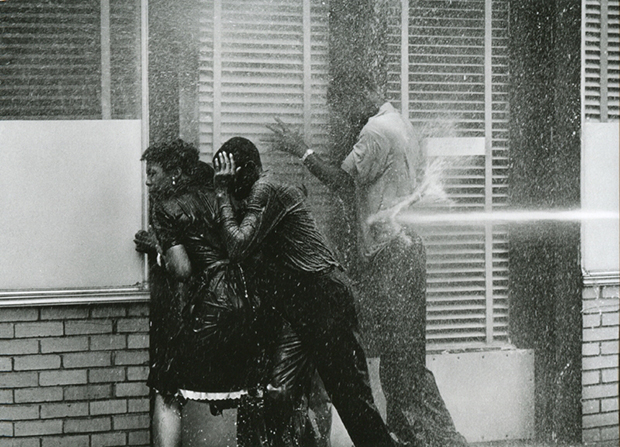

Despite King’s pacifism, and images such as Martin’s, violence regularly entered into the civil-rights struggle after the turn of the decade. Life magazine's Charles Moore documented this change, capturing the treatment of protestors in Birmingham, Alabama in May 1963, when the police, learning that local jails were full, used fire hoses and attack dogs to keep protestors out of the city’s downtown area.

While these tactics may have proved effective in the short term, images Moore took that day only strengthened the widespread condemnation of Dr. King’s opponents. “The jet of the water-cannon probes and compresses its black subjects between two white rectangles in a picture standing as an emblem of the black–white divide at issue in civil rights agitation in the 1960s,” Jeffrey explains.

Moore was born in 1931 in Hackleburg, Alabama and had served three years in the U.S. Marines as a photographer before attending what was then known as the Brooks Institute of Photography in California. U.S. Senator Jacob Javits said that his pictures, many of which were published in Life magazine, "helped spur passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

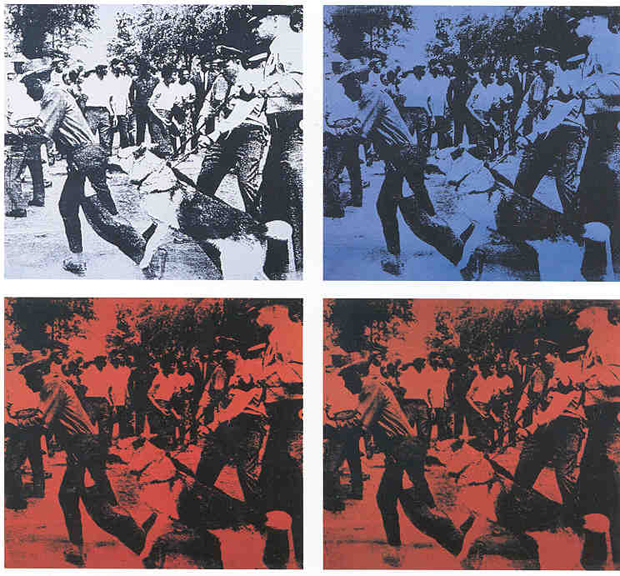

Indeed, his water cannon image had a profound effect on a brilliant, young New York artist, named Andy Warhol. Warhol reproduced Moore’s images of attack dogs assaulting protestors in a set of prints that came to be known as the Race Riot paintings. Andy was not the most politically engaged artist, yet he recognised this as an important, emotive picture, that conveyed the way in which Dr. King and his fellow protestors were changing the country, and the tactics employed by those keen to resist such changes.

For more on these photographs get The Photography Book, here; for more on Warhol’s screen print, buy volume two of our Warhol catalogue raisonné here; and for further images from the Civil Rights Movement, as well as plenty more besides, consider Danny Lyon's career overview, The Seventh Dog. Finally, be sure to check out Freedom, a monumental visual record of African American history since the 19th-century.