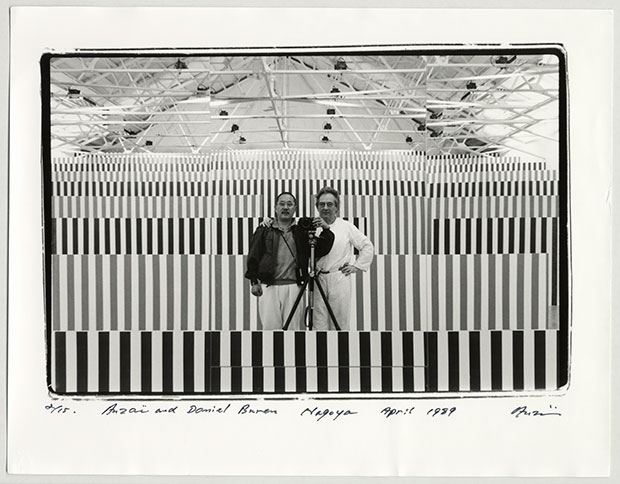

Shigeo Anzaï's pictures from an exhibition (or two)

A new show features the photographer who documented the nation's art movements including Mono-ha

Shortly before Christmas a great little show opened at White Rainbow in London. It’s actually the first of two shows (the second is in May) at the gallery featuring the work of Japanese photographer Shigeo Anzaï.

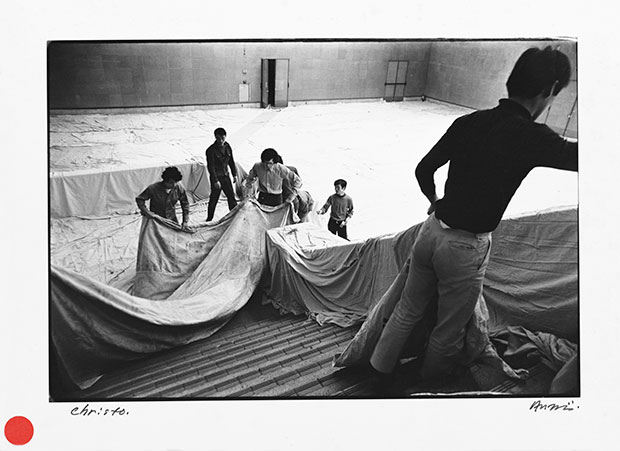

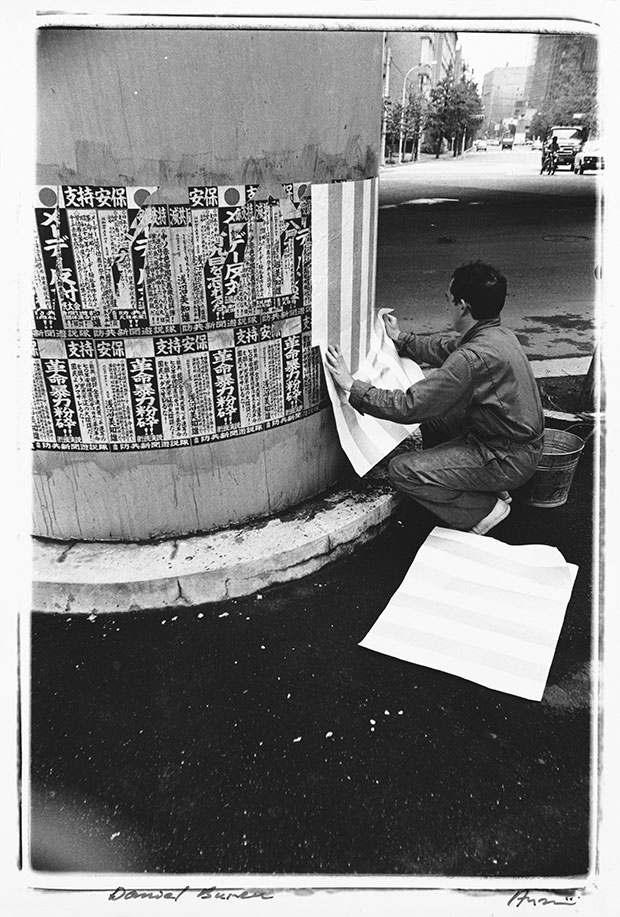

Anzaï is pretty much unknown outside Japan, which is odd considering that during his lifetime he’s photographed the likes of Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Joseph Beuys, Takashi Murakami, David Hockney, Christo and Richard Serra to name but a few and has catalogued numerous important art movements and shows since the early 1970s. Anzaï’s photography is pretty much an index of recent Japanese art history and where it encountered, or was exposed to, international movements.

So many of the images in the show are of ephemeral art, work that lasted for just a moment and then was gone forever. So his photos are of historical importance in terms of Japan’s contemporary art scene as well as the international art scene.

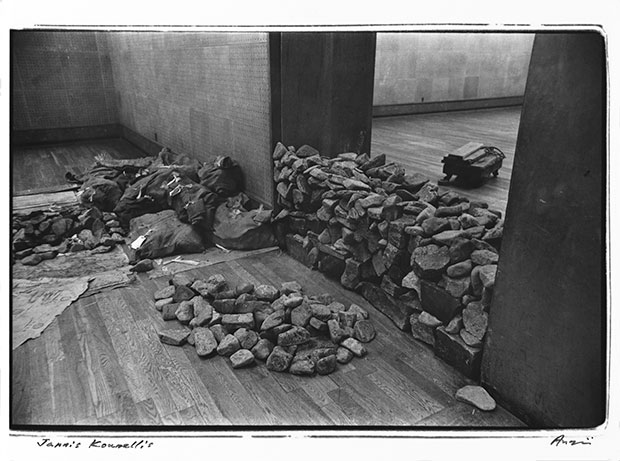

He’s most closely linked with the Japanese Mono-ha (School of Things )art movement of the early 1970s which explored the encounter between, and the space surrounding, natural and industrial materials, such as stone, steel, glass, cotton, wood, wire, rope and water, arranging them in mostly unaltered, ephemeral states.

It emerged in response to a number of social, cultural and political precedents set in the 1960s. With the exception of Lee Ufan, who was a decade older, most of the Mono-ha artists were at the start of their careers when the violent student protests of 1968–69 occurred.

Our best selling book Art in Time: A World History of Styles and Movements has a chapter devoted to Mona-ha, part of which reveals that the term Mona-ha itself, was first applied as a pejorative one to describe the trend among Japanese artists of placing or arranging natural or industrial materials directly on the ground or other surfaces. Mona-ha insisted on the removal of the artist’s voice altogether, critiquing human agency and production by emplying ‘unmediated’ materials,” the chapter reads.

“Refuting the idea that the world is ‘nothing but a territory to be colonized’ by man and his abstract concepts, philosopher artist Lee Ufan presented Mono-ha as a return to a pre-rational recognition of the elemental ‘process of seeing, feeling and touching each other in interactive relationships’.

As Art in Time points out, the first Mono-ha work is generally accepted to be Nobuo Sekine’s Phase Mother Earth – an artwork Anzaï documented and has a story to tell about.

It is a cylinder of stratified earth excavated from an identically sized hole, hardened and recast by mixing cement into the soil. “Phase Mother Earth was demolished at the end of its initial exhibition and refabricated on site for all subsequent shows. This impermanence and reliance on the environment, common to Mono-ha works, emphasizes the relationship between viewer, site and artwork,” according to Art in Time. We asked Shigeo Anzaï what he remembered of the piece and the Mono-ha days.

“Our aim was to build our own identity through the embodiment of our own materials, spacial awareness and bodies. Of course, Arte Povera from Italy, and Conceptual Art from the US and Europe were of great interest and influence but also to differentiate ourselves from the older generation of artists and movements which formed the major scene of the Sixties such as Gutai and Neo-Dada. In the middle of rapid economic growth in Japan, there was a trend towards implementing high tech. In contrast, we had an empathy with natural materials that artists formed work with their own hands. This became their attitude to form, and was realised as Mono-ha within a couple of years.”

The White Rainbow show mainly centres on Anzaï’s photographs circa 1970–76, we wondered why he chose to photograph the work and how important it was to him.

“I was not the only one to regret the loss and disappearance of artworks without trace when exhibitions ended. When Lee Ufan invited me for a chat to a soba noodle restaurant near his exhibition in the Tamura Gallery, he said that if you are so committed why don’t you produce artworks which record ephemeral works? That was the beginning of my practice.” He described the artists as “extremely free, with confidence and conviction. I admire their sense of translucence which is still valid today. They would explore any possibility or pliability within art.” We also asked him for a couple of happy memories from the time.

“In 1969, Hakone Open Air Museum was opened, and from 1973 they ran a prize competition. It was a great opportunity for the younger artists at the time.

Nobuo Sekine showcased a series titled Phase of Nothingness, that had a big piece of natural stone on top of a stainless steel pedestal. This was supposed to be realised with a few Japanese gardeners through traditional methods, but the weight and size made it an impossible task, taking hours with a chain and a pulley to lift the stone. The organiser asked the artist to use a forklift truck but the artist was distressed by this move from his original idea. The work was completed within minutes using heavy equipment, but the artist’s face revealed his mixed feelings.

Then, in July 1970, in a very hot and humid Kyoto, Kishio Suga took part in a survey show titled Trends in Japanese Art and a lot of Mono-ha artists participated. Suga exhibited Infinite Situation (window), where he placed a piece of woodblock to jam the sash windows open. Of course, there were many complaints because the museum could not turn on the air-conditioning because of the open window! But Suga himself did not care and did not alter his work. It was a refreshingly poignant scene that’s still very much alive in my mind.

The show continues at White Rainbow in London until January 23 and you can read more about Mono-ha, Gutai, Neo-Dada and a myriad of other art movements in our book Art in Time: A World History of Styles and Movements.