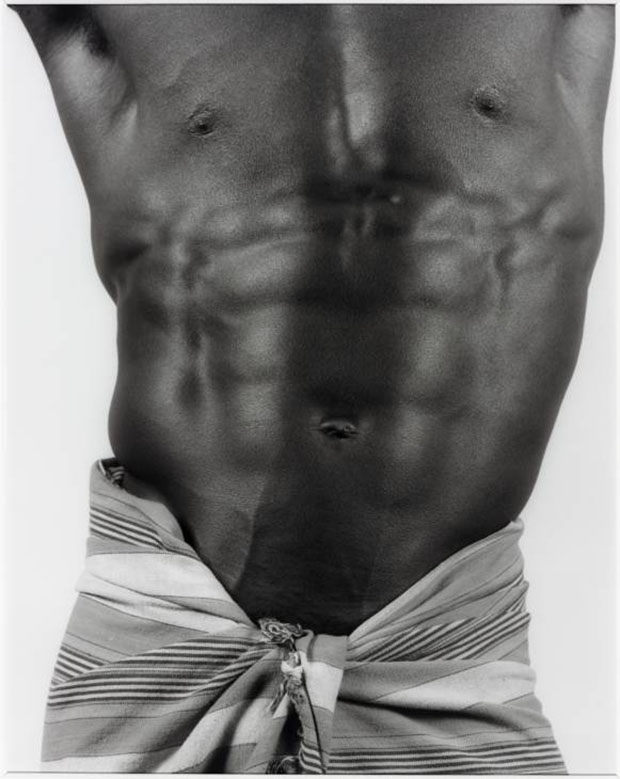

Photos that changed the world #10 Derrick Cross

On the anniversary of his untimely death we look at how Robert Mapplethorpe's astonishing 1983 photograph mixed potent sexual and political imagery - proving that photography could appeal to both the mind and the senses

At first sight, the photo above may not look much more than a picture of a black male torso with the musculature clearly defined. Yet it's creator, the late New York photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, was an incredibly accomplished iconographer, preoccupied by the construction and interpretation of his pictures.

So look a little closer and in this case you may notice that the nipples and the navel of his subject, the late dancer Derrick Cross, suggest that the torso might also be a face. And carefully lit from either side, the middle of the body contains another shadowy figure rising across the pelvic muscles and into the chest and looking, with its slightly dipped head and raised right arm, like the raised fist Black Power symbol of the 1960s. Alternatively, you may discern in the raised figure the outline of an erect phallus.

In his photographs of Cross and the athlete and model Ken Moody, Mapplethorpe’s aim was to show photography as an art that could itself appeal simultaneously to both the mind and the senses. Mapplethorpe’s sexualized and fetishizing representations of the black male body can be seen to echo Leni Riefensthal’s ethnographic photographs of the Nuba and a number of Mapplethorpe’s depictions of black men made use of racial myths that exploit black virility.

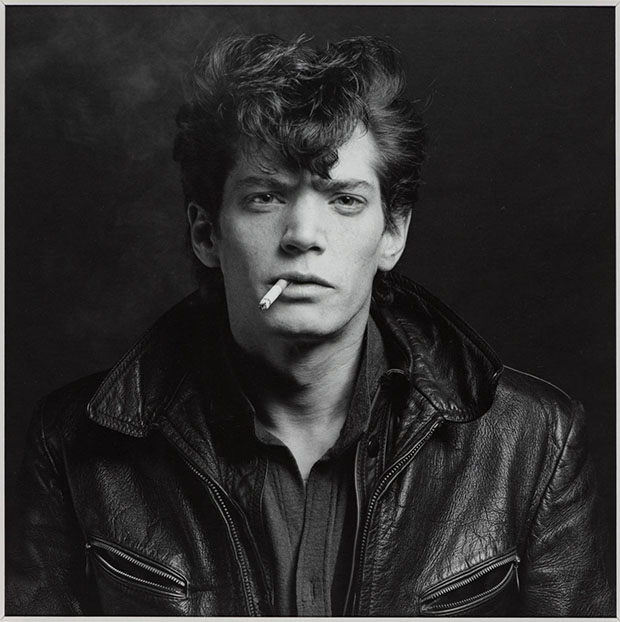

As The Photography Book reveals, Mapplethorpe “preferred to photograph classic themes but made his name through his homoerotic images.” The singer and lifelong Mapplethorpe companion Patti Smith, put it this way in her book, Just Kids. "Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art. He worked without apology, investing the homosexual with grandeur, masculinity, and enviable nobility. Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace.”

Crucial changes in context brought about by the moral panic in the US around the homoerotic content of Mapplethorpe’s work have affected readings of his pictures. His death in 1989 from AIDS, a subsequent obscenity trial and the political assault by the Right on funding for the arts in the US led to a re-appraisal of his photography. Photography Today notes that the respected art historian and cultural commentator Kobena Mercer shifted his initial critical response to the photographer’s work and began to see something both affirmative and subversive in Mapplethorpe’s depiction of black bodies in the ideals of Classical Greek sculpture. Black men in the United States, ‘disenfranchised, disadvantaged and disempowered as a distinct collective subject in the late capitalist underclass,’ are ‘elevated onto the pedestal of the transcendental Western aesthetic ideal,’ he wrote.

Nearly a year before his death this day (March 9) in 1989, the ailing Mapplethorpe helped found the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. His vision was that it would be "the appropriate vehicle to protect his work, to advance his creative vision, and to promote the causes he cared about".

Since his death, the Foundation has not only functioned as his official estate and helped promote his work throughout the world, it has also raised and donated millions of dollars to fund medical research in the fight against AIDS and HIV infection. It's just one of the many ways Mapplethorpe changed the way we digest photographic cues and clues. You can visit the foundation here, and find out more about the hidden depths of Mapplethorpe’s work in The Photography Book and Photography Today. You can also read previous entries in our Photos That Changed The World series on Weegee, Ansel Adams, Richard Avedon, George Silk and Eadweard Muybridge; and if you like what you've read, you'll find a whole lot more in The Photography Book here. Finally, here's an interview with its author, Ian Jeffrey.