Danny Lyon looks back at his powerful prison photos

The brilliant photographer describes the how he got into Texan prisons and why the experience still haunts him

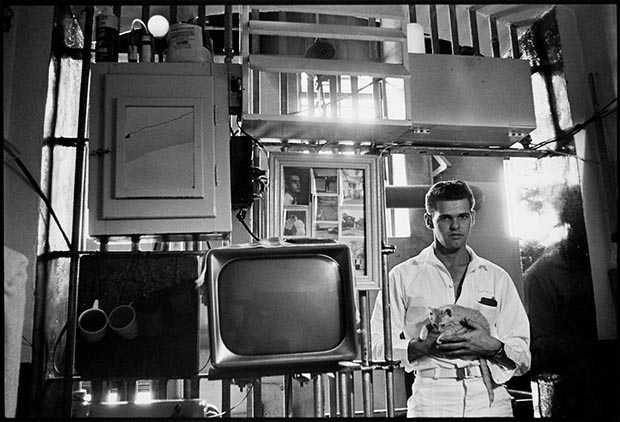

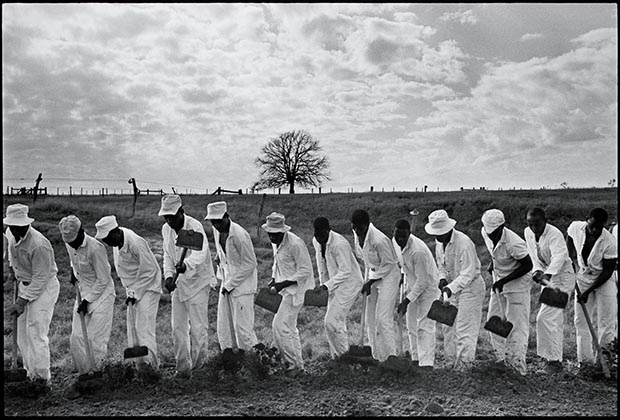

Danny Lyon’s 1971 photo book, Conversations With the Dead, is so affecting a work that, over four decades since the photographer completed this survey of Texan prisons, Lyon remains truly engaged with the subject.

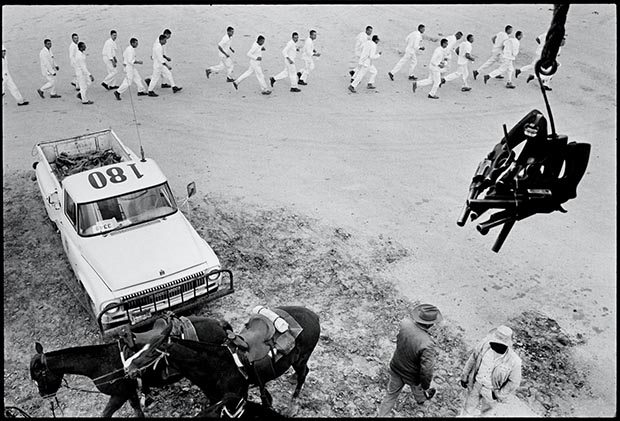

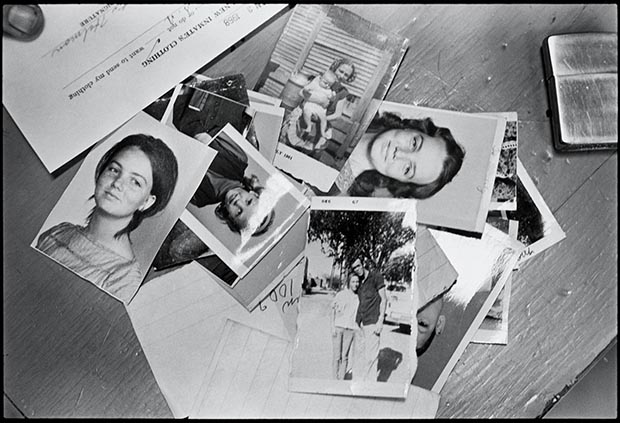

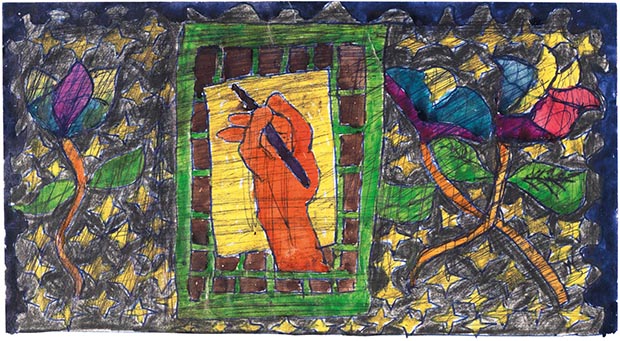

The photographer, who was born in Brooklyn and began his career as part of the civil-rights movement, shot this series in six Texas penitentiaries over the course of 14 months during 1967 and '68. Danny befriended quite a few of the inmates; one, Billy McCune, even contributed letters and drawings to Lyon’s book.

Alas, the lives of Lyon’s subjects did not improve greatly since he took these images were taken. Yet the enduring quality of the shots attest to both Danny’s talents and the prisoners’ own humanity.

Phaidon will publish a new edition of Lyon’s book at the beginning of next month, around the same time an exhibition of these prints opens at the Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York.

Read on to discover how it felt to walk through beside these cells, which of the subjects made it out alive and why, even as a visitor, prison changed Lyon, “and not in the way I could have predicted.”

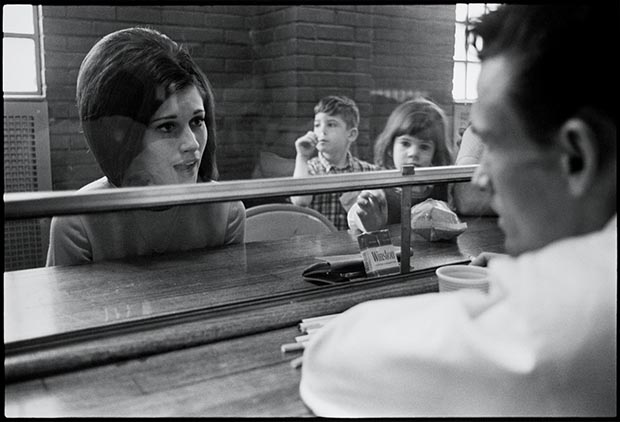

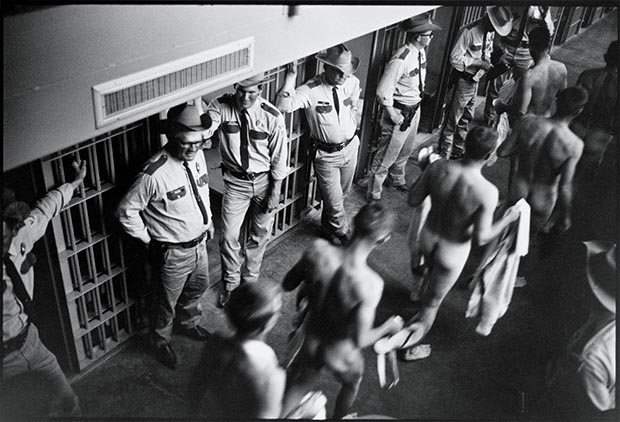

How would you describe in words, now, the feeling you got standing in the corridor of Ellis Prison in Texas? "Ellis was an awful place, so bad, that being sent there was used as a threat to convicts that were in the Walls, or on other prison farms. It was a drive to get there, maybe half an hour through the woods from where I was living in Midway Texas. Over time I got to know a few of the men in Ellis. One was notorious, because among other things he had escaped. I’m sure he was doing life, and his name was stenciled on his white shirt. So when I approached him I knew with whom I was speaking, I knew his history. They even had a cellblock inside Ellis for “the worst of the worst”. Meaning that in that cellblock, were the worst, most dangerous men in Ellis, which was supposedly a collection of the worst men in the entire prison system. And of course this convict lived there in that cellblock. And what he said to me was “there is nothing but a bunch of frightened men in here.”

"But the boy I knew the most there was Charlie Lowe, who was doing Life for the murder of a prison guard when he escaped from Gatesville, a Boys Home so notorious that in the 1980’s a Federal Judge shut Gatesville down. I would visit Charlie inside his cell. Most all the names I used in the book are real names. But for some reason, I changed Charlie’s name to J. Snowday. John Snowday was, in fact a close college friend of mine who had died at twenty-three, so I used his name instead of Charlie’s in the book. In researching the new edition I learned that Charlie was alive and free. We texted each other! Then spoke at length on the phone. Almost all of my friends from that time, McCune, Jones, Renton, are dead. Its nice to know that one of them, a boy I knew in Ellis, a murderer, walked out after ten years or so, and has been free and fine ever since."

You were in jail briefly yourself with Martin Luther King. What did that teach you? Can you describe the experience a little? "I met Dr. King a number of times; the best was when I happened to be entering the Atlanta Airport with my boss, James Forman, the Executive Director of the SNCC [The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee]. Of course Forman knew King very well, and Forman was kind of proud of me, and it was a running joke that he, Forman, had a white chauffeur (me, as I owned an old Oldsmobile and drove him around, jumping out and opening the door for him to impress other people in the south). Forman really “discovered me” in Georgia and made me a part of the SNCC. That day at the airport, Dr. King was holding a copy of Time Magazine, with his own picture on the cover, perhaps he was Man of the Year, or had won the Noble prize. Anyway Forman said, “I want you to meet young Danny Lyon. Danny is the SNCC photographer” (Kings group, the SCLC, didn’t have a photographer, none of the civil rights groups had one, I had basically invented the job with Forman’s support). So I shook Dr. King’s hand, but I really wanted to take his picture, my camera was hanging on my shoulder. Dr. King was holding an almost life size picture of himself across his chest, the Time cover, and showing it off, but I didn’t do it. I thought it was funny, meaning it would make him look ridiculous and I just couldn’t do it. It’s one of the very few times in my life that I regret I didn’t have the guts to do what I wanted."

Was there one incident in your youth that radicalized you, made you become a force for change and a campaigning photographer? "Yeah. The Russian Revolution, The French Revolution and the American Revolution. I missed all of them."

What challenges did you encounter shooting in the prison system back then? Did you ever feel at all threatened by the guards or the prisoners? " I was never afraid of the men. I liked them. And I had many friends inside the system that would stand up for me, dangerous men. Anyway in my heart of hearts I felt I was doing something good for the men, and most of them knew it. The guards were another thing. I couldn’t relate to them at all. Once I was invited to Thanksgiving dinner by an officer “you and your wife, please come over”, and I was horrified. It wasn’t my wife (I had lied about that); it was Rachel, my girlfriend living with me out on a ranch. I’m just not very good at dinners anyway, but the thought of sitting down with god fearing Baptists in East Texas over Thanksgiving terrified me so much, I just told some lie and got out of it. Today I would go just for the food."

The letters from Billy are extremely poignant. What kind of emotion do they instil in you now, when you look back at them? "Billy McCune was a remarkable man, who led a life of great suffering. If you really start reading his words, then seeing how he could draw and paint, you begin to wonder if he wasn’t a genius. As a teen he was put into the Mexia home for retarded children, Texas, because his IQ measured below 80. A great man really. Too bad he didn’t live to see the book re-issued. He would have loved it. He did get out of prison, thank God and lived the last twenty-five years of his life, a free man. He was very, very proud of his place in the book, and then with me, doing The Autobiography of Billy McCune."

What do you remember about that last meeting with Billy? And did he ever say what he had been doing in NY in the intervening years. "As I think you know our meeting was arranged by an audio recorder Matt Orzug, and the results are on the net. I also write about it in the new edition. Within Phaidon there was debate as to whether I should add anything to the book or not. In the end I felt I wanted to speak out about the criminal justice system, which has finally appeared on the radar of American politicians, so I added the postscript. Because I was so much older when I met Billy (I was twenty-seven when we met in Texas, and I was in my sixties, I think, when we met again in Kansas City), I was very moved to see Billy again. He is a very impressive person. I’m glad I knew him when I did."

What sort of perspective on human existence did this photographic project leave you and does it mirror at all what you’ve learned from your other work with disenfranchised and outsider communities over the years? "The prison changed me a lot, and not in the way I could have predicted. There is an expression about dope, “once the needle goes in, it never comes out.” I never really shook the Texas Prison off. I still know people doing long straight time in prison, and I’m occasionally in touch with people I knew inside in Texas. I’m going to show the Texas work in Tucson, at the Etherton Gallery, in November and I keep thinking I would like Charlie Lowe, who has been free for forty years, to come to show. I’ll be doing a book signing at the gallery, and I'd just like to say to someone, “Talk to Charlie, he’s standing over there with his wife. He was a prisoner. I was just visiting.”"

Pre-order Conversations with the Dead here, and check back soon for more on this brilliant book.