Photos that changed the world: #3 Moonrise

How Ansel Adams' technical skill turned a fleeting scene into the new ideal for US landscape photography

Picture the scene: it’s autumn 1941 and you and your assistants are approaching the end of a fruitless day’s work trying to capture the beauty of the US landscape for the Department of the Interior. After hours of failed exposures and missed opportunities you spot, just off Route 84 in New Mexico, a beautiful scene. The white clouds and snowcapped mountains on the far horizon reflect the setting sun; in the foreground an assortment of gravestones also throw off the sinking rays; and, in the sky above, a gibbous moon is on the rise. With the right film, set at the correct exposure, you think it could make for a truly great landscape photograph. Only, where have you put that light meter?

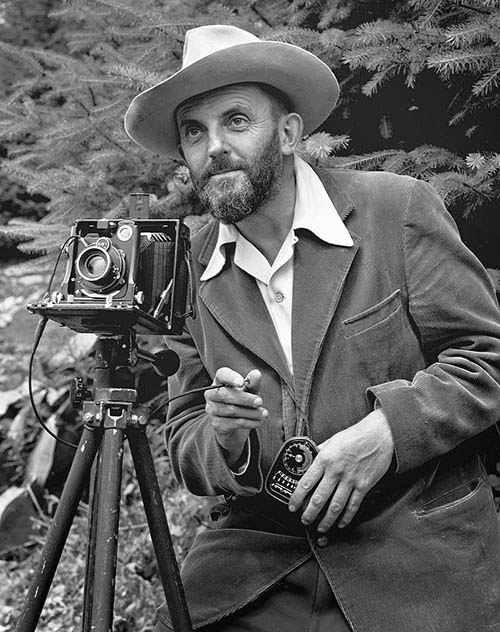

This was the scenario that presented itself to the Brilliant American landscape photographer Ansel Adams, just prior to him capturing Moonrise over Hernandez, New Mexico. A decade or two earlier, and any other well-trained photographer would have sighed and driven on by. The narrow limits of photographic film, coupled with the difficulties measuring the strength of light in a given setting would have made it impossible to photograph this landscape with any degree of accuracy.

However, over the preceding few years, Adams and fellow American photographers, including Willard Van Dyke and Imogen Cunningham, had perfected a new style of broad, sharp, long-exposure landscape photography. The group even named themselves Group f.64, after the tiny lens aperture they favoured when taking these large-scale shots with a remarkable depth of field.

Adams’ highly technical style of photography was made somewhat easier with the advent of new technology, such as cheap, handheld light meters, which allowed photographers to calculate the ideal exposure for a given scene. These were fine when setting up a carefully composed stable, day-lit landscape for a bulky 8X10 camera, though they were less reliable when trying to capture fleeting details in the gloaming.

So how did Adams manage to snap this beautiful landscape with such accuracy? Well, most accounts describe the photographer bringing his car to a screeching halt, pulling his large-format camera out, and frantically hunting around for his Weston light meter. No one could place the damn device, yet he and his assistants realized that, given the diminished glow of the setting sun, accurately photographing the scene would prove near impossible.

However, Adams, now well schooled in light readings, already knew that the moon threw off approximately 250 c/ft2 of luminescence. Working with this figure, he calculated that a shot such as this would require a one-second exposure and an aperture setting of f/32.

Unsure of this first shot, Adams and co. readied themselves for another exposure, yet, by the time they had reloaded the camera, the sun had sunk and the magic had drained away from the landscape.

Fortunately, given the photographer’s specialized technical knowledge and his artful composure, Adams was able to capture the beauty of the landscape despite these marginal conditions.

Here’s how Ian Jeffrey described the picture in The Photography Book. “In this, one of the most epic of Adam’s landscapes, humanity is signalled by a field of scattered crosses in the near foreground. The settlement itself makes an irregular diminishing rhythm from left to right, in contrast to the flowing horizontals of the mountain range and the swift, painterly markings in the sky. The whole of this musicality is related to the imperceptible slowness of the moon rising.”

The beauty of the picture lies in Adams – who trained as a pianist – recognizing the natural harmony in the scene. Yet that beauty is brought out through Adams’ technical skill. The detail, composition and technical brilliance of a shot like Moonrise influenced a subsequent generation of landscape photographers, such as Gabriele Basilico and Edward Burtynsky, as well as practitioners such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth who, while not always shooting traditional landscapes, combine a scientific knowledge of how to shoot a large-scale pin-sharp scene, with an artist’s eye when composing those scenes.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this edited extract from our new book. Look out for more in the coming days, and if you like what you've read, you can check out The Photography Book here.