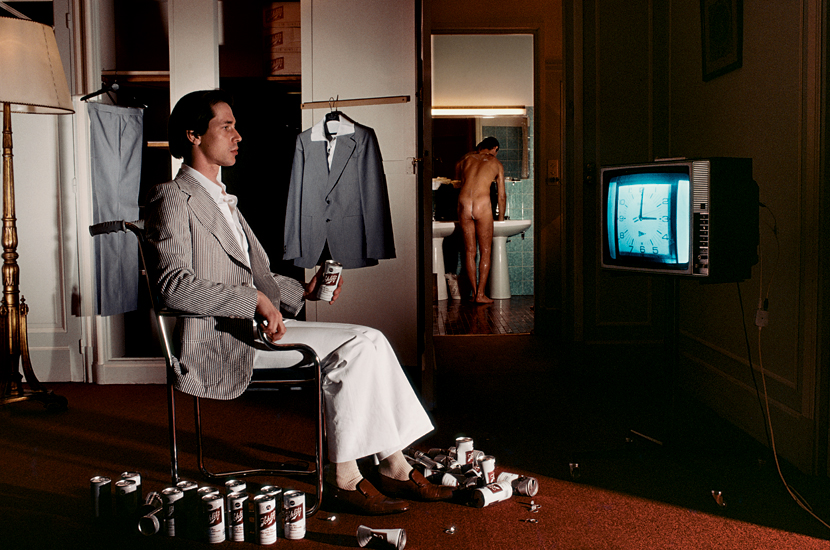

Gratuitous sex, death and Guy Bourdin

Why did the photographer only find true fame after his death? Our iBook author Alison Gingeras has the answer

Today, the late French photographer Guy Bourdin is widely recognised as one of the great image makers of the 20th century. His photos, shot largely for fashion magazines, capture something essential about the sexually-awakened, self-obsessed post-war decades in the West. Yet, at the time of his death in 1991, Bourdin’s reputation hadn’t reached far beyond fashion circles

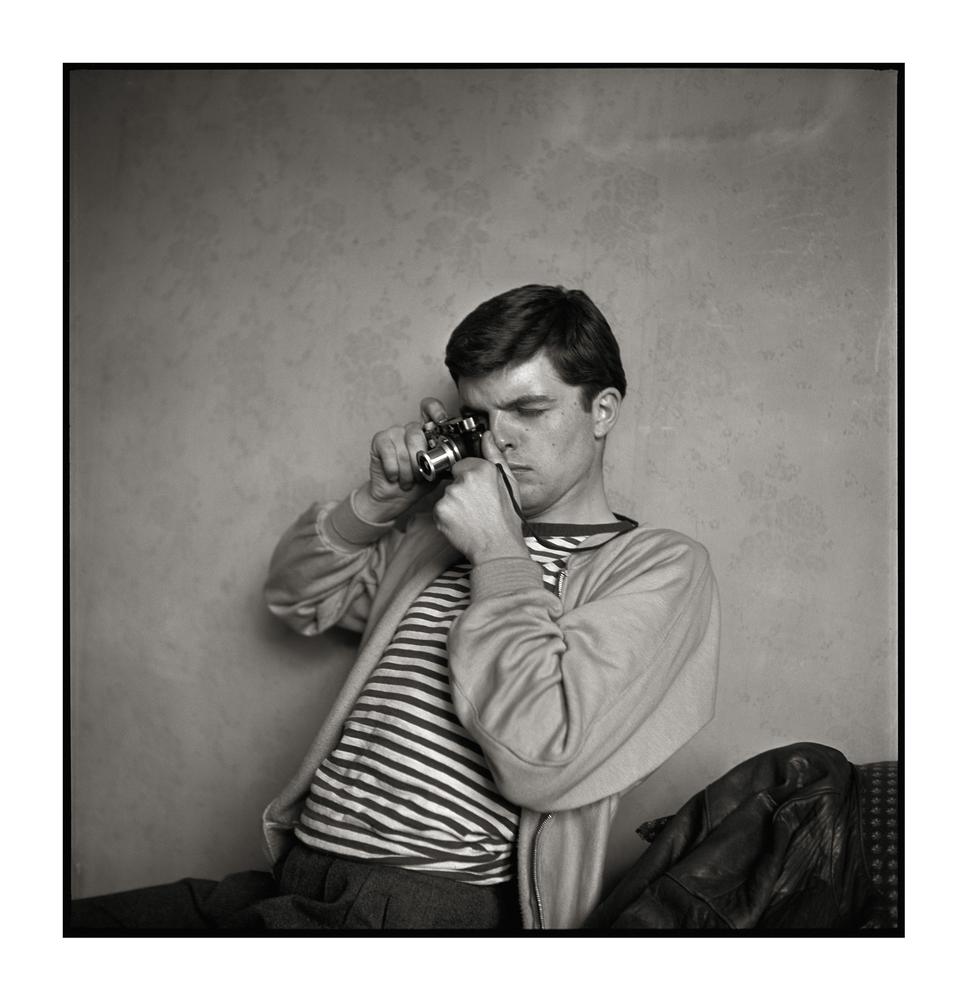

Why did this enigmatic photographer, who is the subject of a major new London retrospective at Somerset House, flourish posthumously? Perhaps because Bourdin himself desired anonymity, as the author of our monograph suggests in a new article for Vogue.

Despite being a meticulous image maker, heavily influenced by the French surrealists, Alison M Gingeras writes, Bourdin cared little for his photos once the fashion magazines were off the shelf or an advertising campaign had run its course, served its purpose.

“Bourdin refused to exhibit or sell his fashion photographs,” Gingeras explains; “he turned down offers to publish monographic studies of his work; the only ‘book’ he ever made was a lingerie catalogue for Bloomingdale's in 1976.”

Some of this impermanence suited Bourdin’s métier, as Gingeras notes. “At the height of his career, Bourdin's work was exclusively visible on the pages of fashion magazines, an intrinsically perishable medium,” she writes. “He embraced the way his images were consumed and then thrown away. This transience corresponded to the enigmatic public persona Bourdin projected.”

Others have suggested that Bourdin’s troubled private life and troublesome personality may have led him to shun the spotlight. In either case, the photographer’s lack of public profile only adds to enigmatic quality of an already uncanny collection of images.

“In the age of the ‘selfie’, Instagram and unapologetic self-promotion, thwarting celebrity seems almost incomprehensible,” Gingeras writes. “Fortunately for the cultural world, there has been a slow shift since Bourdin's death in 1991. Several scholarly publications over the past decade have ‘rediscovered’ his radical photography, giving Bourdin his rightful due as a serious auteur.”

Gingeras has played her own part in this shift, yet she doesn’t wholly disapprove of Bourdin distancing himself personally from images, perhaps because, in 2014, his works are rightfully judged on its own merits.

“Today, it's clear that Bourdin's photographs from the Seventies foresaw the entertainment industry's desire to shape us into consumers of gratuitous sex and death,” she writes. “And although his efforts to shun fame might seem at odds with our current taste for celebrity, his images conflating glamour, mortality and eroticism have emerged as perfect emblems of our time.”

For more on the exhibition, which opens today and runs until 15 March, go here. To gain greater insight into Bourdin’s life and work, download Gingeras’ book here.