Daido Moriyama and the scent of the city

How the Japanese photographer always looks for the dim light in a shadowy environment

You'll often hear Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama talking about the "scent of cities" and how he's guided through them by his own "sense of smell". The city, to Moriyama, is a work of art, albeit one he so often paints in with a monochrome palette.

For the most part, his high contrast, grainy, black and white photos seem to reflect his attraction to what he calls "a dim light in a shadowy environment." He's described his photography as "abstract and symbolic, one could say it is a dream world." But his is a dream world sprung from a very real one.

The best of his photography has chronicled the breakdown of traditional values in post war Japan. In order to reflect that breakdown, Muriyama has always opened himself to new ways of thinking about photography. One of the most remarkable of these ways of thinking is his approach to the spontaneous, accidental images found at the beginnings and ends of film rolls, the often unintentionally exposed and higher contrast images he views not as as the work of the photographer but of the camera.

This is just one of the many photographic kinds of exploration you'll find in our new Phaidon 55 iBook - a great place to start finding out about his work, gathering together, as it does, many of his best images spanning the late 1960s to the early 1990s. It's released this week and below is just a little taster of what you'll find if you download it here.

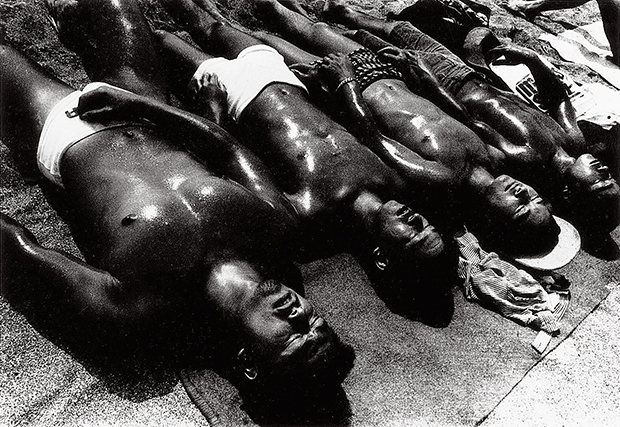

Beach Boys, Zushi, Japan, 1967 (above) Youths smeared in sun tan lotion lie, like ‘packed sardines’ in Moriyama’s words, on Shonan Beach in Zushi, where he was living at the time. He often shot a number of similar objects arranged in echelon like this. Moriyama was one of the first photographers to reflect on overcrowding and the loss of individuality in contemporary life. Oiled and inert, his subjects represent a degree-zero of self-indulgence. In the new postwar Japan, this kind of carnality was at variance with the stricter ethics of the old order. Japanese photographers were fascinated by the contrast.

Baton Twirls, Tokyo, Japan, 1967 Moriyama may have encountered this scene as he stepped from a coffee shop somewhere around Jiyugaoka, where he had made a break on his journey from Zushi to Tokyo, on the suburban Toyoko Line. These uniformed high-steppers in their shako caps represent the new Japan, infiltrated by American influences of all sorts. Although others saw this as cultural contamination, Moriyama appears non-judgemental.

Fence, Yokota, Japan, 1969 Moriyama took this picture of a Japanese couple through the windscreen of a moving car in Yokota, the largest US military base in Tokyo. One can see from the woman's dress that she is a bar hostess, probably working at an establishment catering for American soldiers. It is day-break and hostess and patron seem drunk and exhausted. In the US, Garry, Winogrand had photographed events through the windscreen in the mid-1960s. Moriyama's scenes, however, are both more fleeting, more melodramatic.

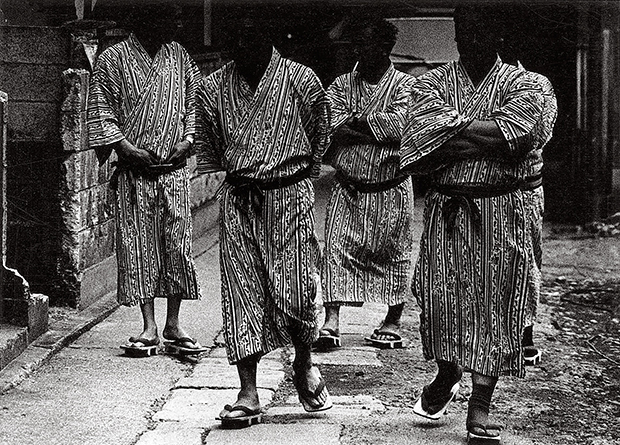

Hot Spring Resort, Gunma, Japan, 1979 With their faces hidden, the anonymous men, all dressed in the yukata (a relaxed evening kimono), evoke a slightly different version of the much-photographed Japanese 'salary man' culture. Objectively lit, this would have been a conventional group portrait. As it is, we are forced to gauge character from what we would normally think of as secondary evidence - posture and gesture, for example. Although nothing definite can be learned from such evidence, we make the attempt anyway. Moriyama has always been interested in the encryption of photographs, in their suggestive rather than their descriptive capabilities.

Evening Scene, Aomori, Japan, 1977 Aomori’s Pepsi drinkers seem to have gone home, and the business of the day to have reached its conclusion. The shadows cast on the walls of buildings suggest that the sun is going down, leaving only evidence of the mundane activities of work and leisure. This is, of course, a documentary picture, but of a new kind, which presents the inhabited environment as a transitional zone crossed by wires, rails and tracks. This kind of disinterested approach to topography originated in the 1970s and was perfectly suited to Moriyama’s outlook.

Riot, Tokyo, Japan, 1969 The original title of this picture was 10.21 - 21 October, then recognized as International Anti-War Day. Students in the anti-Government movement Zenkyoto and young labourers in the Anti-War Youth Committee clashed with riot squads, demanding the return of Okinawa and the non-renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty. This picture was taken underneath the real railway viaduct on Yasunkuni Street in Shinjuku. Typically, little can be made out clearly, which would reflect the experience of rioting on the night-time streets of a modern city. Student riots, with their general aims seemed at the time to be expressions of the zeitgeist and could not be explained in conventional terms of cause and effect. Like what you've seen and read so far? Then download the iBook here.