The melancholy life of the amazing André Kertész

Though a master of composition, the Hungarian photographer could never really find himself in the frame

Although his name is whispered in hushed tones among many of today's photographers (our own Roger Ballen included) throughout much of his life Hungarian photographer André Kertész laboured much if not unknown then at least overlooked - to his own mind at least. Deeply reserved, Kertész consistently remained true to his beliefs and origins. His work, which received belated recognition from the 1960s on - with another ignitive spark in the 1980s - always drew on his personal life yet never lapsed into autobiography.

As a young man in the early 1920s, he photographed the Hungarian peasants around him. His clarity of style, emotional connection with his subjects and the geometric patterning of his photographs were evident from the outset. For Kertész, taking a photograph involved encapsulating an atmosphere but also solving compositional problems linking form to content.

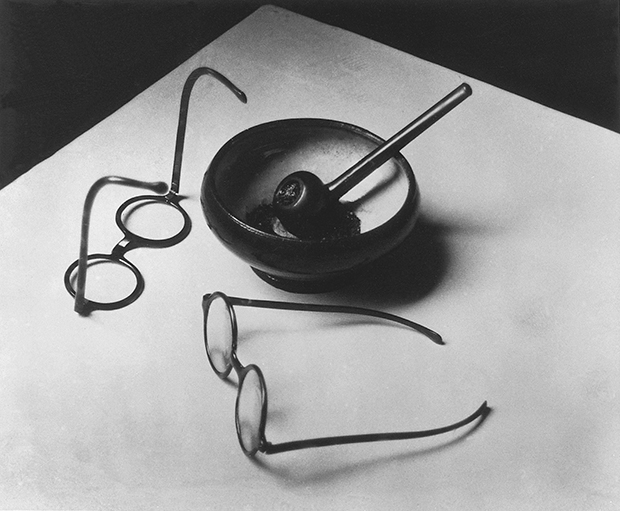

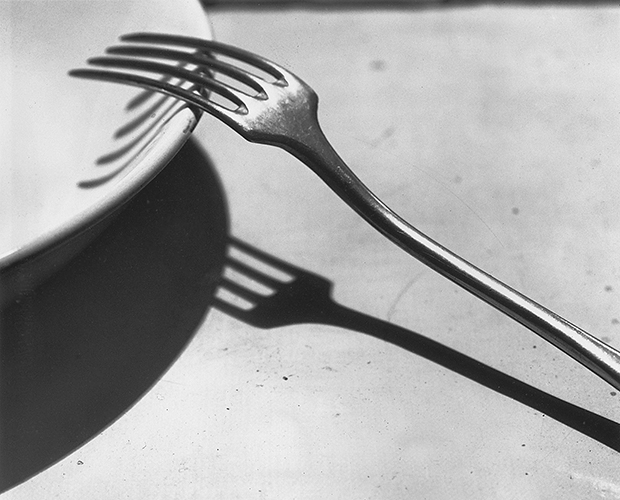

Susan Sontag has described his work as 'a wing of pathos'. Certainly, his photographs, The Fork and Mondrian's Pipe and Glasses not only constitue admirable formal compositions, but seem to elevate seemingly trivial details into quite meditative poems. All of which makes us all the happier that he is one of the initial photographers featured in our new Phaidon 55 iBook series which launches next week.

As Kertész's photographs began to be published in magazines so his confidence grew. In 1925 he moved to Paris where he threw himself into the art scene, becoming connected to the Dada movement and taking photographs every day. As persecution of the Jews increased he moved to New York which, as Surrealism and Constructivism began to run out of steam in Europe, supplanted Paris and Berlin as the centre of artistic creation. Kertész drew more commissions and his work spread.

Towards the end of his life however, Kertész often spoke of the lack of close contact with other artists. In Paris, he had created his masterpieces in Mondrian's home or at the Hotel des Terrasses. In New York, he officiated at the Saks stores or at Winthrop Rockefeller's home. The surroundings had changed but he had remained the same. Those who knew him in his later years recall his fatalism and an inclination towards melancholy. Isolated in New York, eternally rootless, without contact with other artists, nothing really stimuated him.

He died in New York in 1985 leaving behind 100,000 negatives many of which to this day, remain unseen. It was Henri Cartier-Bresson who perhaps provided the most fitting tribute when he said: "Each time Andre Kertész's shutter clicks, I feel his heart beating." For now, enjoy the photos and their descriptions below and when you've done that check out the book on iTunes.

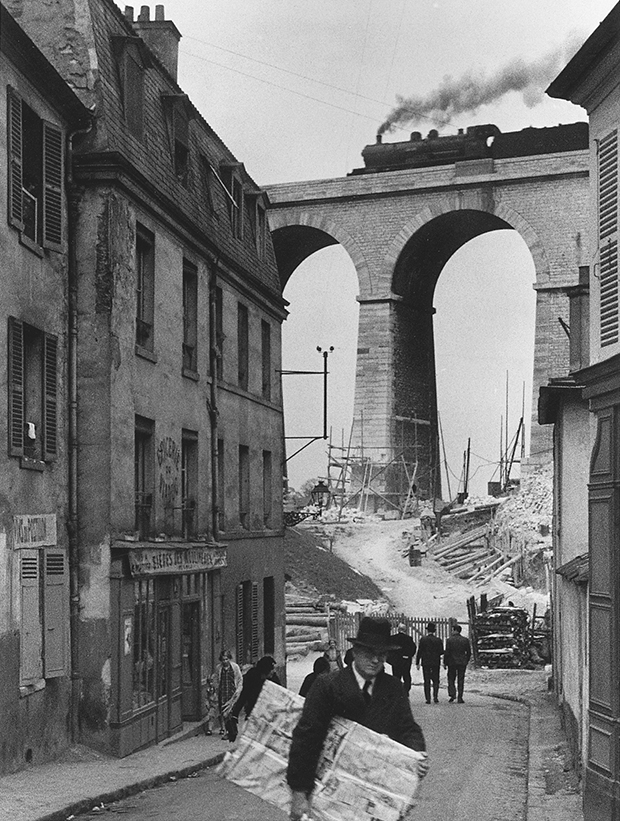

Meudon, France, 1928 Kertész used a Leica to produce this miraculous snapshot. This camera first appeared in Germany in the 1920s. Kertész began using one in 1928, three years prior to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Light and easy to handle, it used film on rolls, and was to become the favourite camera of photojournalists. A vision of movement and speed, capturing people walking in the street and the engine powering over the viaduct, this photograph is an example of what the leader of the Surrealists, André Breton, described as ‘opportune magic’. It is thought that the man in the foreground may be the German painter Willi Baumeister, and the parcel he is holding the stretcher of a canvas. Kertész had known him since 1926, when he photographed him in the company of Mondrian and Seuphor.

Lost Cloud, New York, 1937 It was unusual for Kertész to give his works proper titles such as this, as opposed to captions used for filing purposes (date, place, names of individuals, etc.). The adjective ‘lost’ endows the cloud with a personal, emotional dimension. The picture can be seen as an allegory of Kertesz’s own displacement – far from the artistic fraternity of Montparnasse, poorly used professionally, and cut off from his roots.

The Circus, Budapest, 1920 Kertész often photographed people who were in the act of looking, rather than focusing on what they were looking at. This photograph, ironically entitled The Circus, frustrates our voyeuristic curiosity in order to show us the importance of looking. The simplicity of the composition saves the image from being merely an amusing vignette, however, endowing it with value as a metaphor for the photographer’s abiding question: what is truly worth looking at?

The Fork, Paris, 1928 This photograph was shown at the ‘Salon de l’Escalier’ (Paris, 1928) and at ‘Film und Foto’ (Stuttgart, 1929) and was used in an advertisement for the silversmiths Bruckman-Bestecke. The purity of the composition matches the function of the object – the fork is not depicted merely as a formally beautiful object, but also retains its qualities as a utensil. With this vivid description of the spirit of an object, Kertész fulfilled an important artistic goal.

Mondrian’s Pipe and Glasses, Paris, 1926 (main image, top of story) First shown in 1927 at the Au Sacre du Printemps gallery, this photograph synthesizes the modernist ideas promoted especially by L’Esprit nouveau (The New Spirit, 1920–25). This journal, founded by poet Paul Dermée, Le Corbusier and the painter Amédée Ozenfant, promoted new forms of expression, which aimed to express the ‘lyrical beauty’ of the world of objects. Through his instinctive ability to integrate refined, abstract forms, Kertész captures the spirit of Mondrian’s paintings.

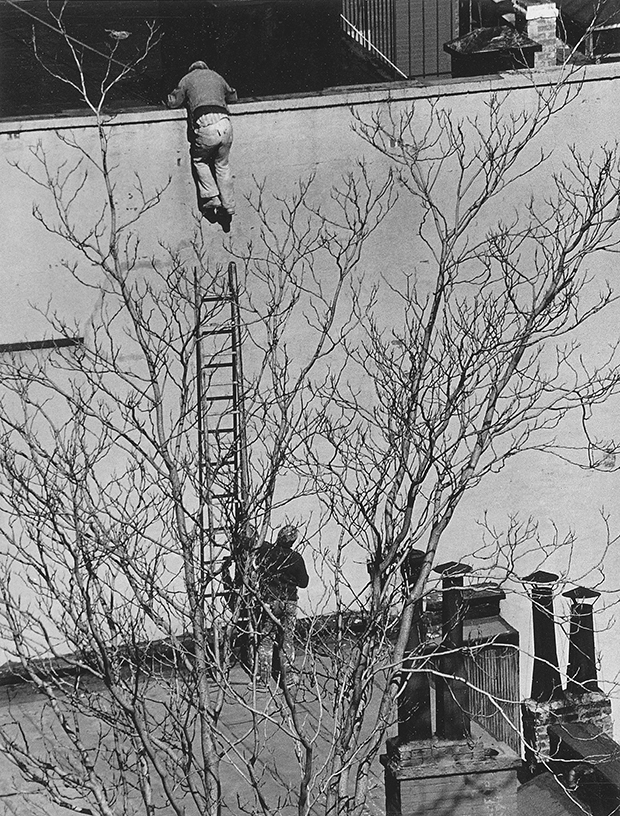

New York, 1975 When taking high-angle shots, Kertész frequently used a zoom lens. In this way, he compensated for his unchanging vantage point through the possibility of surveying a great variety of visual fields. Even if, at the age of eighty-one, the streets were now out of bounds to Kertész, he never completely abandoned the subjects dear to his heart. These photographs echo the series ‘As from my window I sometimes glance’ (1957–58) taken by voluntary recluse W. Eugene Smith from the window of his Sixth Avenue apartment. You can find the André Kertész Phaidon 55 iBook here.