Ten questions for Martin Parr and Gerry Badger

Our selfie-taking photobook experts on rarity, collecting and why the photograph is like a time machine

Gerry Badger might not be as well-known as his collaborator Martin Parr, but the photographer, architect and writer and co-author of our Photobook series is hugely talented and highly knowledgeable, and so we were very pleased to spend some time with him yesterday, while he and Martin signed copies of their latest book, The Photobook: A History Volume III.

As with the preceding volumes, Gerry has assembled the book with Martin, and once again his insight, critical faculties and broad knowledge of the history of photography has contributed massively to its success. Read on to discover which photobooks Gerry is still looking for, why a photograph of Rembrandt would beat the artist’s own self portrait, and how, for him, photographs can function like a time machine. Martin arrived halfway through our chat, and he shares his insights too - along with a selfie he snapped of them both (above). Quite a treat, then, for photo fans everywhere, just like their new book.

How did you and Martin meet, and how do you work together today? I can’t tell you, because we don’t know; I guess it was at some opening. If you’re on the photography scene, you just run into people at openings and get talking. We were probably talking about someone like Tony Ray-Jones. I do remember that Martin wanted me to write something for a show he was putting together. That was back in the early nineties. It was supposed to feature six British photographers, including Chris Killip and Paul Graham. I remember us all going up to Martin’s house in Liverpool – we had a rather merry weekend. For the Photobooks, I go down to Bristol, Martin spreads a pile of books out on the floor for consideration and we just go through them. I write the text. I also devised the structure of the book; it was a question of getting the books we’d missed, and books that had come to our attention since we’d done the first two volumes.

Why do we like photographs, what is it that the best ones do to us? They take you 'there'. They take you to places that you can’t go to, like the surface of the moon, and they also form memories, they take you to long ago. They allow you to travel through time and space. Here's an example. There are Rembrandt self-portraits, and they date from the seventeenth century, and they’re painted by Rembrandt, an icon of the art world. But if you actually had a photograph of Rembrandt, it would be more powerful, in that sense I’ve just outlined, no matter how crummy a photograph it was. It wouldn’t be a great work of art, but it would take you there. People go on about the superiority of painting, but in that area photography can’t be beaten. We’ve quoted the American artist and photographer Lewis Baltz, who said that photography was a narrow but deep area between the novel and film. That’s a very good way of thinking about it, especially in relation to the photobook.

Why the trend for art galleries printing up and displaying huge single photographs? If you go back, historically, photography has always had this inferiority complex with painting. So, to give photography equal weighting with painting, you print it six-feet wide. Very often all you get is a six-foot wide photograph. All it’s really saying is that the image is trying to compete with painting, so the gallery can charge so many thousands of dollars for a print. I remember standing and looking at some very big prints by a well-known German photographer, with John Gossage, a leading American photographer. The prices for these prints were really high. John said ‘what do you think of them?’ I demurred a little, and he said, ‘yes, they’re all icing and no cake.’ That’s often what you get with large photographs. Printing a bad photograph large doesn't make it good, it just makes it large.

What should our readers look for when buying a photographic print? I always advise to buy vintage, which means prints made within about five years of the negative being made. It shouldn’t always be printed by the photographer, because some of the greatest photographers didn’t print their own work. It doesn’t necessarily have to be signed either. In fact, it’s sometimes a bad sign if it’s signed, because in the 1930s, why would a photographer sign their prints? There was no art market in photography. You also have to find out how many were made, and that isn’t always clear, because dealers would tend to tell you fewer rather than more. The provenance of the print is very important – that’s why the best ones go for over a million, because all those facts are very clear.

Harry Lunn, the US dealer who created the photographic market, once addressed a symposium back in the seventies. He had two photographs. He said, ‘Here I have a print by Robert Frank from the Americans which I retail for $10,000. Here I have another print by Robert Frank from the Americans, the same picture, which I also retail for $10,000.’ Then he tore one in half and said, ‘Now I have this print by Robert Frank from the Americans which I retail for $30,000.’ As Harry always used to say ‘We’re in the business of creating rarity value.’ That’s the art market.

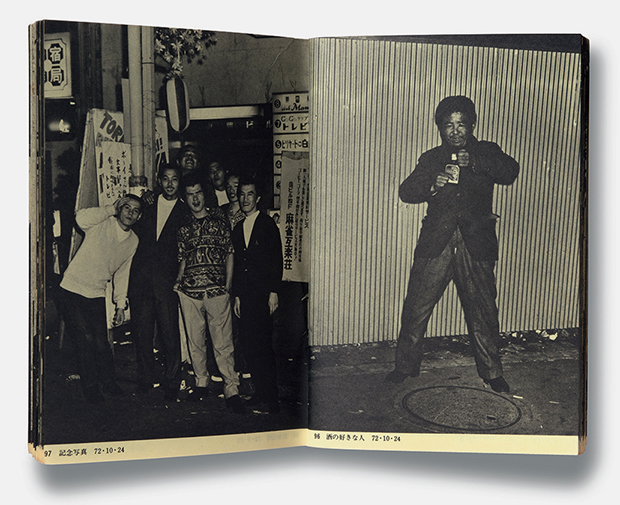

So how does that affect the market for photobooks? The collector’s market for books always tends to be there. The problem with the great photobooks is that there’s often only an edition of 2,000. Just through natural wastage, 500 would go immediately. Take one of the Japanese titles in this book, The Gangs of Shinjuku by Watanabe Katsumi; there was a fire or flood at the warehouse where that initial print run was first stored, and so that book is suddenly rare. We’re accused of raising the prices, but all we’re trying to do is write a history of the photography through the photobook. It’s an unfortunately upshot of the book. The fortunate side is that certain classic books will be republished.

[At this point Martin Parr comes in; he’s twisted his leg badly at South Bromley tube station, and can’t walk properly]

Gerry, people sometimes say Martin's work is a little misanthropic. Is that fair? [Martin laughs] No, that’s unfair. He wouldn’t be a good photographer if he was so one note. There are all sorts of things in his work; they run the gamut of being sharp at times to being really warm hearted and sentimental, and that’s good. That represents the breadth of a good artist’s work.

The most re-tweeted picture was a self-portrait by Ellen DeGeneres at the Oscars. Does that say anything about photography at the moment? Well, you could say it’s very shallow. But it’s only saying one thing about one aspect of photography. I was reading an interesting book about about self-portraiture, from the Old Masters up to the selfie. It described the self-portrait as once having a spiritual element, and now it has a material element. It was about self-examination, now it’s about self-publicity. That’s a decline.

Do you need a grounding in photography to appreciate The Photobook? I hope not. It’s not an academic book; it’s a book by two enthusiasts. Mind you, the history here is far greater here than we first imagined. It’s like finding an ancient city and digging. The more you dig, the more unexpected connections you find. The other things you notice are the connections between books; between an American book done in the seventies and a Japanese book done in the seventies. Seeing two photographers tackle similar issues – that’s interesting, and they wouldn’t have seen each other’s books.

Are there titles you know are out there, but still can’t find? Martin : Oh yeah. Today, I was sent details of twelve Iranian books, made in and around the Iranian revolution. The dealer wanted over forty thousand dollars for them. I thought it was overpriced. So, I’ve just written to an Iranian photographer to see if they’re available. China is a hidden mystery too; it’s one of the last unknowns. We’ve got some Chinese in here. Italian fascists and Iranian, we’ haven’t put in, because we didn’t know so much about them.

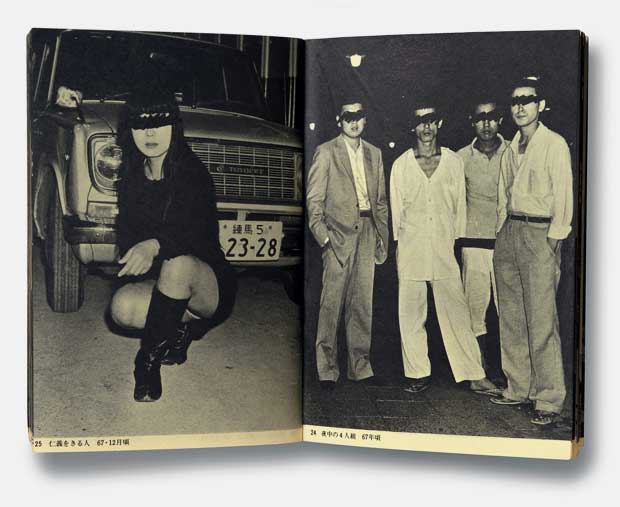

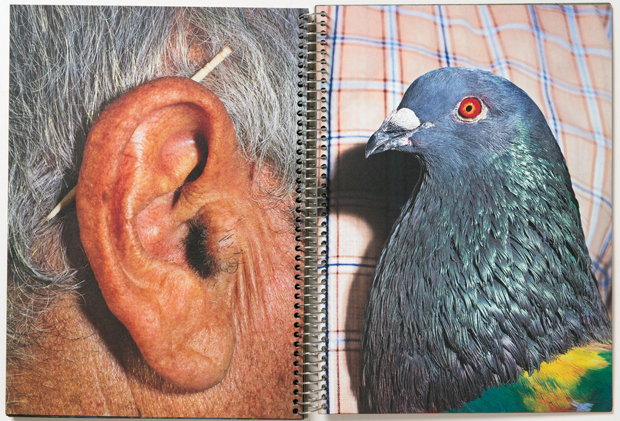

Which books in the Photobook do you really want? Martin: The only one Gerry wants is the bike one.__ Gerry__ : And the fashion one; the long haired youths. They’re both gay books and they’re both Swiss. The cycling one, we think is the first time somebody took newspaper cuttings and made an exquisite artist’s book out of them. And it’s a wonderful book, its touching and funny, it ticks loads of boxes. It’s about bicycle racing, and it does rather focus on crashes. It’s interesting because of the gay subtext.

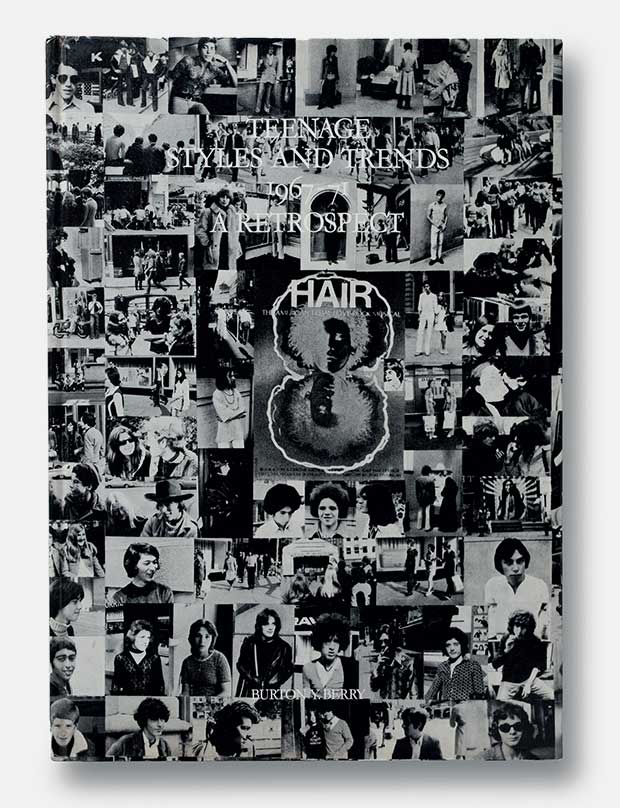

The other Swiss one was by an American diplomat in Zurich. It was called Teenage Styles and Trends 1967 - 71: a Retrospective by Burton Y Berry. It was privately printed. He loved young men having long hair; it was made towards the end of the sixties and the author was in his sixties, and he wrote that it’s lovely how young men can feminise themselves. Really interesting. We’ve quite a few gay male books in there, but, strangely, we didn’t find a lesbian one to include." The Photobook: A History Volume III by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger is available here, now.