The Only Woman in the armed forces

In The Only Woman, Immy Humes gathers together group portraits featuring just one solitary female subject, including these examples, featuring a single female in among servicemen

Immy Humes’ new book, The Only Woman is, according to the author, “essentially, a study of power, as seen in one hundred photographs of groups of grown men—artists, workers, musicians, dentists, lawyers—with only one single woman.”

“Spanning more than a century and a half, from 1862 to 2020, the photos were taken in the United States, the United Kingdom, Mexico, France, Peru, Pakistan, and fourteen other countries,” Humes writes in her introduction. “They capture moments along a wide, slow current of change. Each photo offers forensic evidence of patriarchy on parade, along with all the other forces of domination.”

In some instances, that display of power is soft and covert – the book includes group photos of poets and television script writers, all men, save for one woman – yet in other instances it is far harder and more direct. Consider this picture of Marlene Dietrich (above) of Allied soldiers, taken on the European front during World War II.

“Here, she is working for the US Army, entertaining soldiers in Europe during the war” writes Humes. “A devoted anti-Fascist, Dietrich was horrified by what her native Germany had turned into, and she did wartime service by donating her femininity, her glamour, and her fame, visiting soldiers to encourage them and cheer them up. In that role, she embodied a mix of archetypal Only Woman categories: nurse, sex worker, and angel!”

No one would expect Dietrich to hurl a grenade or carry a rifle, yet her appearance here, as an active participant in the war, demonstrates how powerful she had grown. “Becoming a performer - dancer, singer, actor - has long been a pathway for a woman to enter public life,” writes Humes. “Becoming a star has been a rare chance for a woman to gain real money and power. Showbiz has had many Only Women, who managed to enter and shine, very often one at a time, in a male fantasy on-screen and off.”

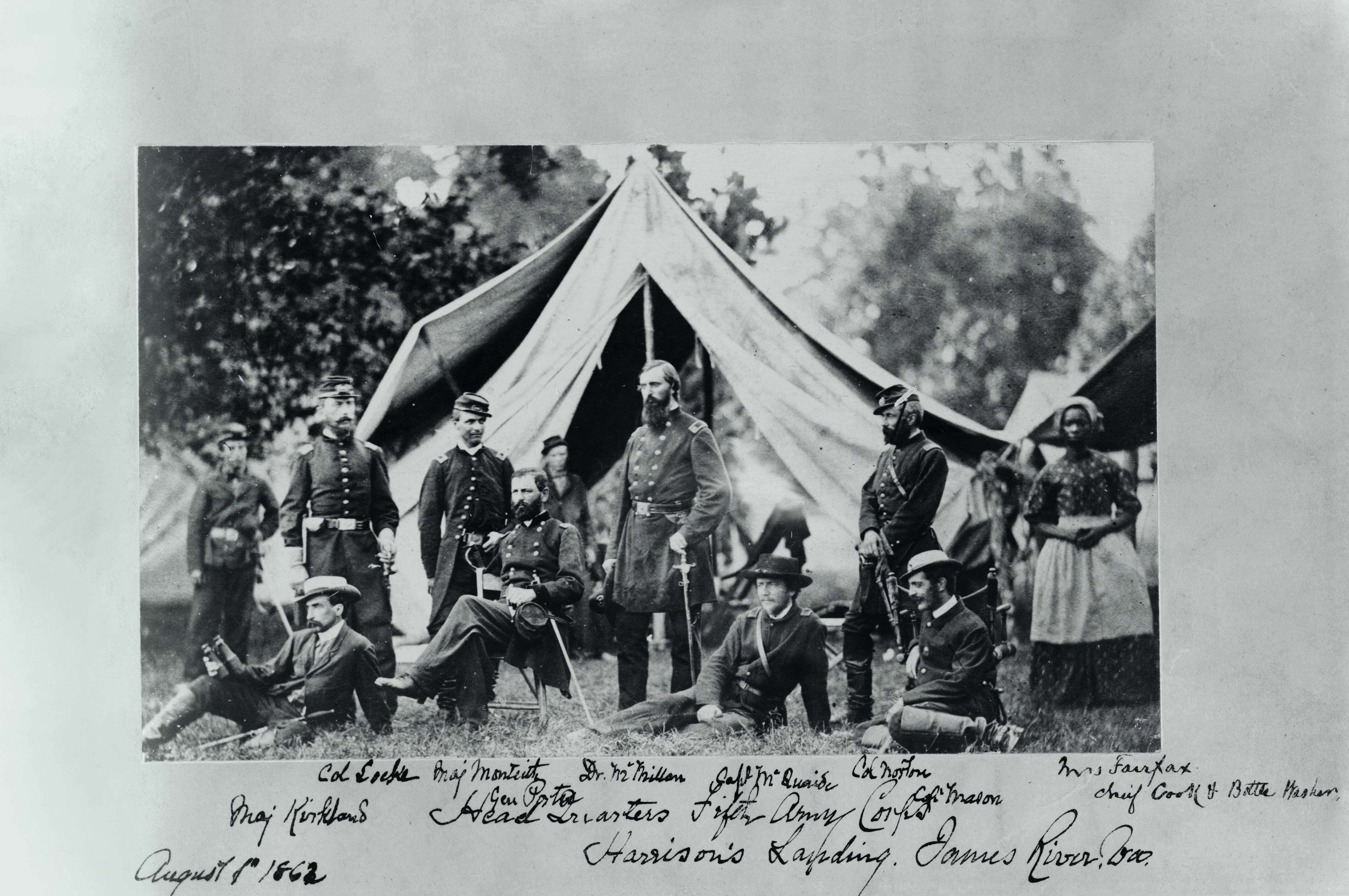

Mrs. Fairfax, Cook, Harrison's Landing, Virginia, USA, 1862

Dietrich’s purely aesthetic role stands in contrast to another female captured in a photograph from an earlier conflict. It is Mrs. Fairfax’s labour, supporting Union General Fitz-John Porter and his staff at the Fifth Army Corps HQ, Harrison’s Landing, James River, during the American Civil War, that justifies her place in this picture.

“She stands off to the side, a little out of focus, but commands the eye,” writes Humes. “The only woman among white men in uniform, Mrs. Fairfax gazes directly at the camera, hands folded in a posture of readiness and service, as the well-fed Yankee officers look off to some imagined horizon, a few weeks after a victory on the James River, near the first-ever plantation in Virginia.”

“Female workers of the war, especially Black women, were usually framed out,” Humes goes on to explain. “Of the many thousands of Civil War–era photographs, few show Black women. When they do appear, they are usually unnamed, like the three shadowy men in the background here.”

Why does Mrs. Fairfax receive not only space in that frame, but also a mention in the caption? Perhaps because her role within this corps’ war effort was vital. “This photograph was a gift from one general (seated) to another. His handwritten caption identifies her as ‘Mrs. Fairfax’, using an honorific that was denied Black women, and ‘Chief Cook and bottle washer,’ an old-fashioned way of saying she did everything and was indispensable.”

Unknown, Mascot, Annapolis, Maryland, USA, 1894

Neither a big-name star, nor an indispensable cook, the role of the sole woman in this final image, in among new graduates at one of the United States’ armed services academies.

“Identified on the negative of this image held by the Library of Congress only as ‘Mascot’ the young woman placed in the centre of this graduating class at the US Naval Academy, staring straight at the camera with a grim expression and a fabulous hat, looks like a lady with her gorgeous outfit,” explains Humes. “But there’s no clue who she was. A daughter of the Superintendent or another officer? A little sister? She is not even a token: she was not admitted with the others—the US Naval Academy didn’t admit women until 1976. She is another, placed at the heart, in a position of honour and presumably affection.”

Today we think of a mascot as a pet animal or anthropomorphic figure. That sort of mascot wasn’t unheard of in the late 1800s; “only the year before this photograph was taken, the Navy football team introduced its first official mascot, a figure who survives today, Bill the Goat,” writes Humes.

However, female figures also fulfilled this role. “Many of the images in this book show the phenomenon of mascotism without naming it so conveniently. A woman who serves as a good luck charm for the group of men is a configuration that predates tokenism. Somehow it was pleasing to the men, and it may well have been flattering and fun for many of the women. Though possibly not this one: she doesn’t look thrilled.”

Her expression stands in contrast to the calm repose of Andrea Motley Crabtree, a US Army Deep Sea Diver, photographed at Panama City, Florida, in 1982.

Andrea Motley Crabtree, US Army Deep Sea Diver, Panama City, Florida, USA, 1982

“‘I love that photo,’” Humes quotes the now retired Master Sergeant Crabtree as saying. “For me, it captures everything. Most of the men hated me being there. The way he’s looking at me with such disgust! He (the onlooker pictured) didn’t make it. He was claustrophobic. He couldn’t understand how I was better than him.’”

Indeed, Sergeant Crabtree excelled. “Of some thirty students who entered in 1982, only eleven made it through, including Motley. She became the first woman deep sea diver for the army, and the first Black woman in US military diving, capable of welding underwater and using heavy equipment in underwater construction and salvage operations.”

Despite these firsts her career did not progress as she might have hoped. “Things really went wrong with a new supervising Master Diver, and when the job of diver was reclassified and closed to women. Instead of sending her to a coveted training slot at the next level, the Army sent a man with lower rank and less experience. The sexism eventually drove her away and still stings: ‘I was a good diver. Why wasn’t that enough?’” Many of the other women in Humes’ book might well raise the same question.

The Only Woman

To see more images like these, and gain insights into the women featured in each shot, order a copy of The Only Woman here.