How the Icelandic economic crash helped give birth to Slippurinn

The 2008 financial crisis devastated Iceland, but it led chef Gísli Matt to look for inspiration close to home

In 2008, when Gísli Matt turned 19, his uncle, the chef Sigurdur Gíslason, opened a restaurant on the top floor of Iceland’s tallest building in Reykjavík. “My father was working construction there and I needed a job, so I went along,” explains Matt in his new book, Slippurinn. “I took out the trash, built tables and helped with anything that needed to be done. When the restaurant opened, there wasn’t really a discussion about it, but I found myself washing dishes and peeling potatoes.”

Eventually he took on cookery work and grew to love the camaraderie and crazy working schedule. “We prepared lunch, arriving at 7 a.m., and the last desserts for banquets were sometimes eaten at 2 a.m. and we would be there cleaning up until 3 a.m.,” he recalls. “I think my longest shift was twenty-one hours. Within three months I went from washing dishes to running a banquet.”

In the year preceding the restaurant’s opening, Iceland’s economy had been running hot, with a substantial expansion of its banking sector. Then, seven months after that skyscraper restaurant’s opening, the 2008 financial crash hit. “The lavish banquets became fewer,” writes Matt. “Cooks left or had to be laid off.” Matt himself became the restaurant’s head of pastry, just as Iceland underwent one of the most profound economic and cultural crises in its history.

As The Economist reported at the time, Iceland’s banking collapse was the biggest, relative to the size of an economy, that any country has ever suffered, and as the banker’s banqueting budgets dwindled, Icelanders began to question the value of the flashy, globalised world.

Matt himself wondered why local foods weren’t more highly valued. “Why don’t we use wild sheep sorrel in our salads anymore? Why do we send dried cod heads and collars to Nigeria instead of eating them like we used to? Why don’t we dry herbs and make our own teas from angelica, Arctic thyme and yarrow?” he writes in his new book. “Why don’t we use the whey that we use to ferment food to create something delicious instead of just preserving it?”

More pressingly, the economic crash pushed Matt and his family towards a different way of life, outside the Icelandic capital. His mother, Katrín Gísladóttir, had a fine arts degree, but couldn’t find much work in Reykjavík. His father was working on fishing boats and taking carpentry jobs, but it was hardly a career. So they decided to move back to Heimaey, the tiny island where Matt was born.

“They were asking me what I wanted to do after graduation and I told them I wanted to prove myself somehow,” the chef recalls. “My mother started talking about the ‘Magni’ building, an old machine workshop in the shipyard in Vestmannaeyjar. She went on to say how beautiful it would be to run a restaurant there. We would call it Slippurinn, which means ‘boat ramp’ or ‘slipway’. We talked into the night and it became this romantic idea. My sister Indíana could design it, I could be the chef and my other sister, Rakel, could do pastries. By 1 a.m. we called a relative who owned the building and told him our crazy idea. He said, great, let’s do it.”

The restaurant opened on 6 July 2012, and has since gained an international reputation for both its veneration of traditional culinary ways and ingredients, and the manner in which it stretches the envelope of contemporary cuisine. Those cod heads that used to go to Nigeria are now cooked with chicken stock, birch and kelp, and blow-torched just prior to presentation, to caramelize the skin.

It’s a dish fit for any international financier, though Matt and his team might not have created this incredible restaurant without focusing a little closer to home.

In his new book, he draws a comparison between the brilliance of Icelandic bands and Slippurinn’s success. “Someone once asked Barði Jóhannsson, the Icelandic musician, what it is that makes Icelandic music so special? He responded, ‘The reason is that all the bands that are any good all know that their music won’t be played on the radio, they know they won’t sell more than 200 albums in Iceland, especially if it is a young band. So, they make music just as they please’.”

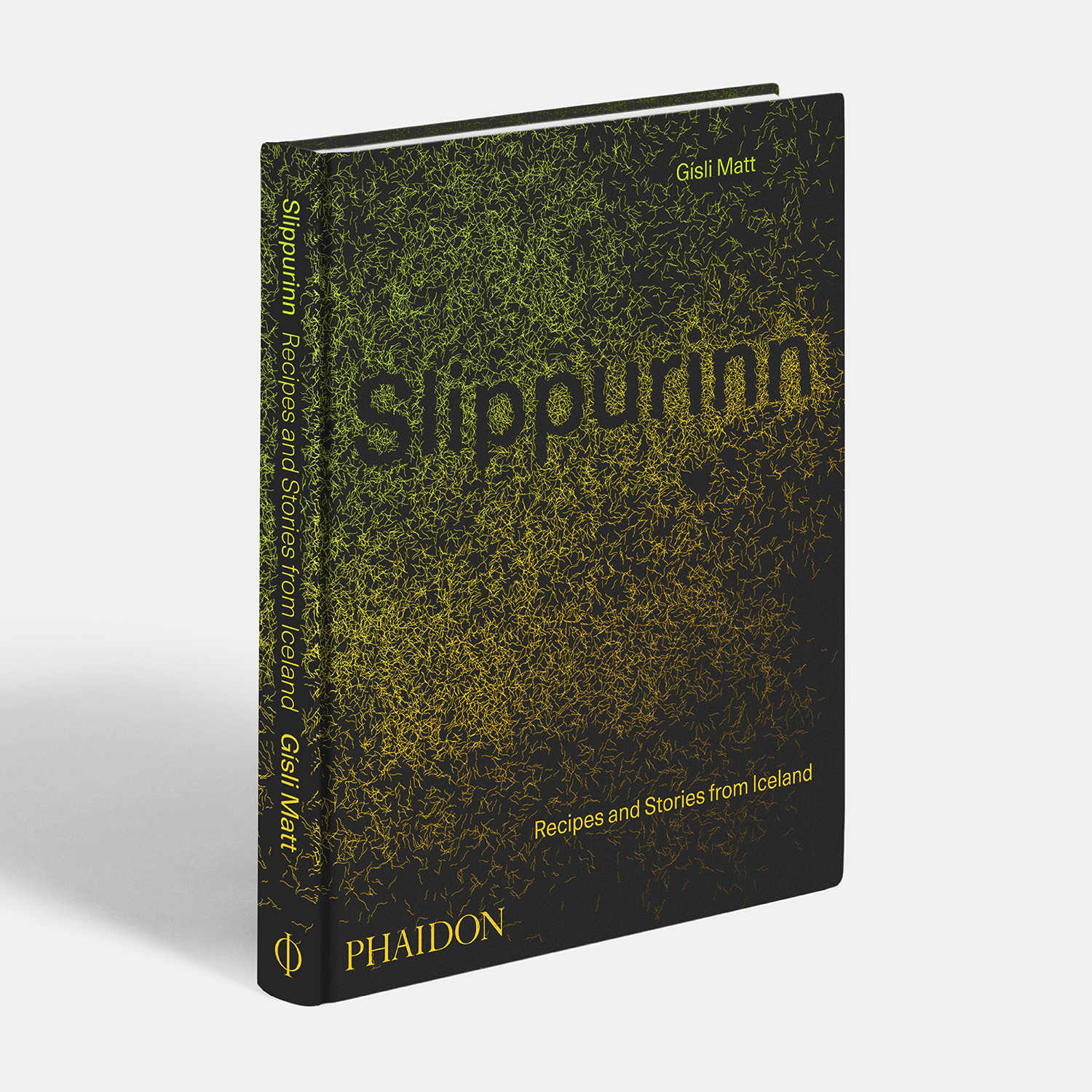

To find out more about this chef and his remarkable, remote restaurant, order a copy of Slippurinn here.