The foraged ingredients that bring a taste of the wild to monk

Patron chef Yoshihiro Imai’s love of the natural world comes through in his choice of wild herbs, nuts, fruits and vegetables

Today, Yoshihiro Imai, the patron chef of monk, attracts discerning diners from across the world to his 14-seat, seasonally inspired restaurant in Kyoto, Japan. It's a beautifully conceived space, manned by a brilliant, focussed chef, who pulls from his wood oven, not only incredible pizzas, but also a seasonal menu, favouring fresh, and sometimes wild local ingredients.

However, Imai’s earliest culinary offerings weren't quite so refined. The chef was born in a small village about 60 miles northeast of Tokyo, and, as a child, he used to love spending time in nature.

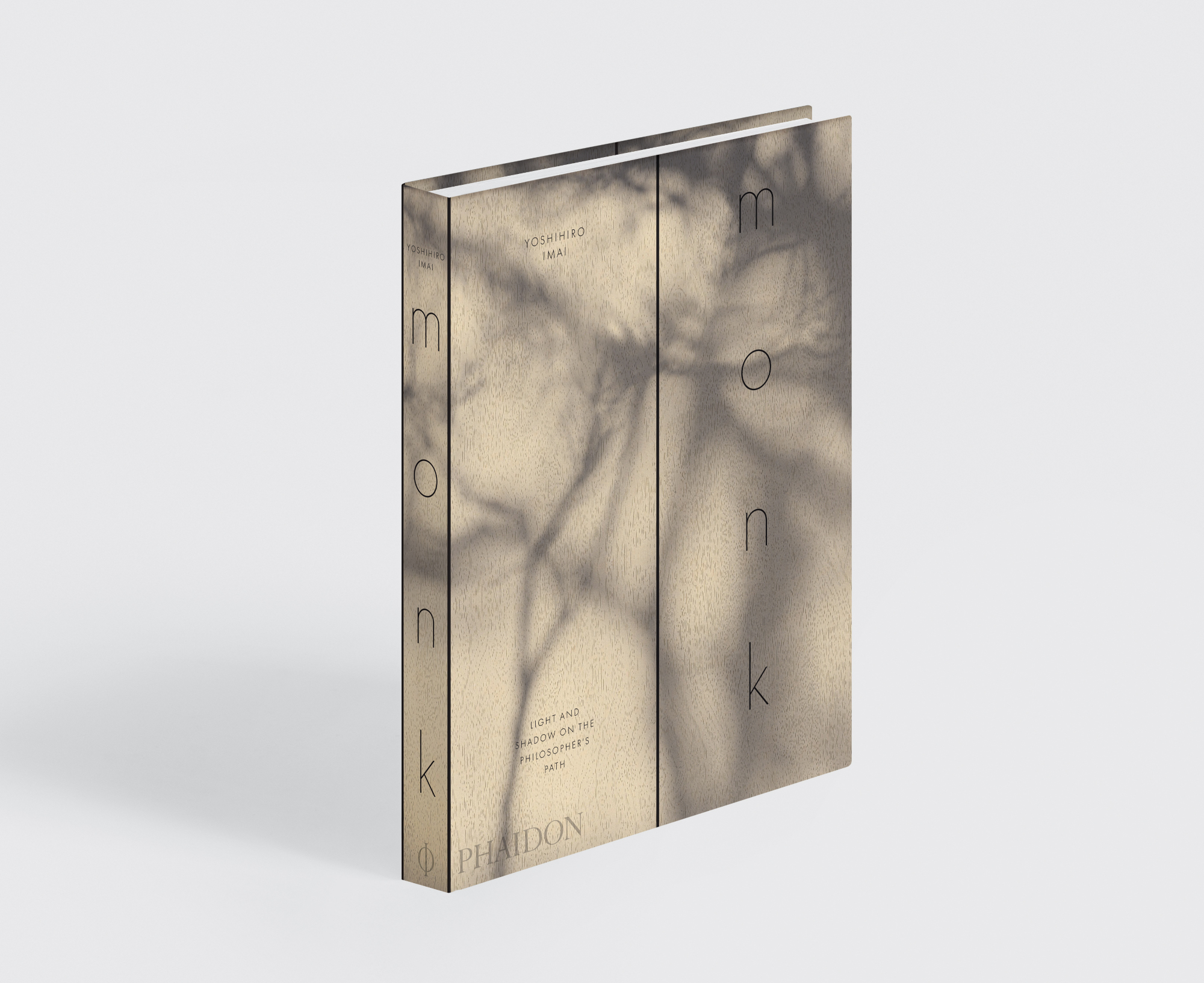

“After school and on weekends, I liked to walk in the forest or fields on my own,” he writes in his new book, monk: Light and Shadow on the Philosopher's Path. “While my friends were off playing soccer, I was out looking for bugs, or picking up nuts, and I still have vivid memories of the plants and creatures I came across in the woods and fields.

“One of my oldest memories of cooking is of gathering firewood to make a small bonfire, dragging over a rusty pot that was given to me, boiling some water in it, and making hard-boiled eggs,” he recalls. Of course, Imai’s gastronomic skills have come a long way since then, but he still manages to bring a little of the wilderness into his kitchen.

“The wild mushrooms at monk are provided by Yu Sasaki, a native of Iwate prefecture in the north of Japan’s main island of Honshu, known for its cold climate and mountainous terrain,” explains the chef. “It’s a great place for mushrooms to grow, and Sasaki knows just where to find the most beautiful specimens.

“Sasaki’s deep knowledge extends beyond mushrooms to include the surrounding forest and vegetation, and the problems the forests are facing today,” Imai goes on. “His study includes the ancient lifestyle of the people of Iwate; the folkloristics and in particular the language of the area; the geological features and their origins; and the contemporary problems of Japanese society locally and globally. Living in a one-hundred-year-old house, he enjoys a simple life without a television or microwave, or other modern electronic appliances.”

Though grateful, the monk chef doesn’t limit himself to Sasaki’s mushrooms, but also cooks with other wild ingredients, some of which he gathers himself. Our new book includes mentions of wild boar, wild herbs, and other ingredients.

“Wild mountain vegetables are the harbingers of spring,” he writes beside his recipe for fiddlehead fern and koshiabura pizza. “At monk, I like using a wild fiddle-head fern called kogomi, and the sprouts of a wild tree called koshiabura to make a half-and-half pizza that bursts with the flavors of spring. The fiddleheads have a nice nutty umami, and pair well with pine nuts. The koshiabura side has a very green taste, so it goes best with just a bit of olive oil and cheese.”

Meanwhile, beside an entry for autumn nuts and egg yolk sauce, he writes that “the rich ginkgo nuts and walnuts are picked in the forest. With these I like to pair a wild fruit called sarunashi, which is a type of kiwi, served with a shio-koji egg yolk sauce. To decorate, I add the petals of Aster yomena, a wildflower similar to a daisy, and tree bark from the forest, bringing the harvest of the season straight to the table.”

To get the recipes for all these dishes as well as much more besides, order a copy of monk here.