Magnus Nilsson's Momentous Moments: The day he met Joel Meyerowitz

A walk with New York’s greatest street photographer taught Magnus Nilsson something crucial about craft, as he recalls in Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End

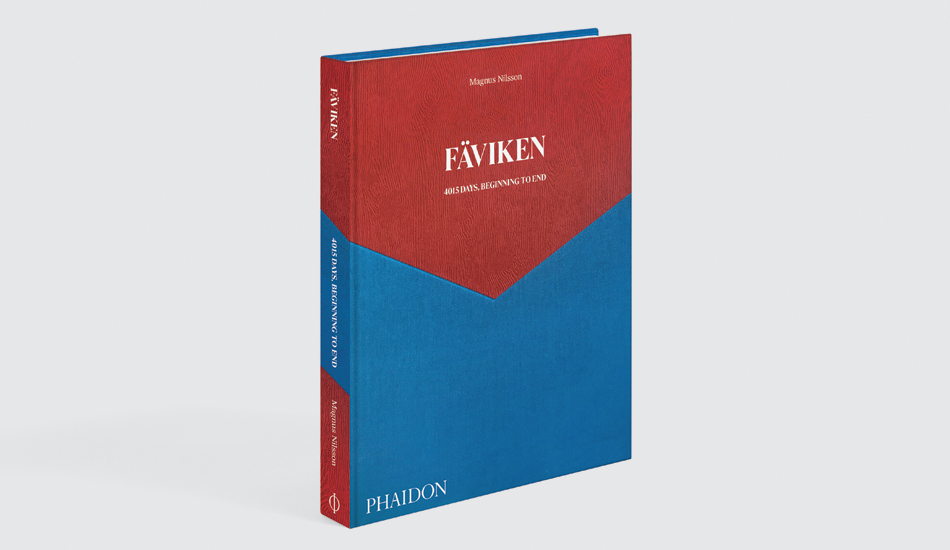

Magnus Nilsson’s new book, Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End, is a remarkable document. The book details a complete list of dishes served at Fäviken in chronological order, and describes not only how a great many of them are cooked, but also how he and his team developed these remarkable creations.

However, the book goes beyond the usual scope of the average cookbook or chef’s monograph. Instead in it, Magnus actually describes how he turned a remote Swedish hunting lodge into one of the world’s most highly praised restaurants, and in the process, developed from a little-known culinary professional into an internationally renowned star chef.

Magnus has a wonderfully candid prose style, and the book is filled with pithy, off-the-cuff insights. Take, for example, this passage, on the skills, or apparent lack of them within haute cuisine.

“Most of the people who are going to play a part in cooking that dish you are going to eat in any expensive restaurant couldn’t replicate the whole dish on their own if their life depended on it,” he writes. “Most of them are, unfortunately, not particularly good at cooking.

“This might sound harsh. Of course, cooks are good at cooking, why wouldn’t they be? Well, first of all it’s usually not the cook’s fault that he or she is not very good at cooking; it’s the industry’s fault and, generally speaking, the more ambitious the restaurant, the more exaggerated the problem. In most of the very best restaurants in the world today, the people who are actually making most of the food have very little experience. They are usually young and ambitious, at the beginning of a hopefully excellent career, young cooks who might one day end up in a restaurant of their own. But they haven’t learned how to cook yet, and sadly, in most of those places no one is going to teach them either.”

Magnus admits that Fäviken ran along similar lines, though he did, in his own way, attempt to impart some knowledge to his staff - up to a point. “I don’t mind teaching,” he writes. “Part of the deal with being a craftsperson is that you pay forward what you were once taught or what you’ve managed to figure out yourself. That is the way teaching and learning a craft should work. The sad thing is that so much of the energy we spend on teaching today if we do it is, in a way, wasted because many of those working in hospitality leave the restaurants they work in and move on too early, or leave the business of hospitality altogether, which is in itself demotivating for the restaurateurs as they rarely get to enjoy the fruits of their investment in someone. It all promotes this culture that devalues teaching. This in its turn further perpetuates a system in which, as a cook, one will inevitably get fed up and leave."

Rather than play the international culinary system, by landing as many prestigious jobs at big-name kitchens as possible, Nilsson believes ambitious young chefs should stay put, and work on their craft.

“You need to learn by making mistakes yourself and by repetition, where you can analyze your own work over time and implement improvements,” he writes. “This can only happen in a natural way if you work somewhere for an extended period of time. So, what is a great craftsperson then? And what is great craft? Well. To me a great craftsperson is someone who masters an act of doing something so well that it becomes second nature to him or her. You are a great craftsperson when your skill stops getting in the way of executing your great ideas. I have met many amazing craftspeople throughout my life and career. Some I took notice of straightaway and some I realized only a lot later what they truly were."

Nilsson realised this not in any particularly hectic service at his restaurant, but actually during a trip to America. “I was walking up Fifth Avenue together with Joel Meyerowitz, the street photographer,” he writes. “For those of you who don’t know him, Joel is one of the greatest living photographers. He has been shooting for almost 60 years and he is an amazing craftsman. As it happens, we have the same publisher and I met him once during some sales conference in London. This was when I was just beginning to start to photograph my own books and I felt like I needed someone to talk to and learn from, so I asked him if I couldn’t accompany him on occasion and perhaps send an email now and then when I had a question. Surprisingly, he said yes and there we were.

“We talked about this and that and walked up the street. The sun was quite low and at each intersection the light came straight from the side and bathed the street in brightness. Like me, Joel was shooting with a Leica, which even in the digital age is pretty much a manual camera where you set the aperture and shutter speed yourself. After having walked for ten or fifteen minutes I realized that Joel without looking at it adjusted the aperture on his lens every time we walked out into one of the bright intersections, and then back again when we had passed it and returned to the shadow of the next building. Not once as we walked, and he was explaining his thoughts of photography, did he talk about this, and not once during the whole walk, which lasted several hours, did he pick up the camera to look at it and check his exposure or settings. Honestly, I don’t think he even thought about the fact he was doing this and yet I am fairly certain that his camera was always perfectly set for an immediate shot.”

Now that’s real craftsmanship. To read more about Nilsson’s career insights and to find out why he really closed his restaurant, order a copy of Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End here. To see Joel’s incredible photography, go here.