Magnus Nilsson's Momentous Moments: The day Magnus realised influence is OK, copying is not!

The words of one hallowed French chef led Nilsson to realise that, in some instances, a re-appropriated recipe idea can be a tribute, rather than a theft

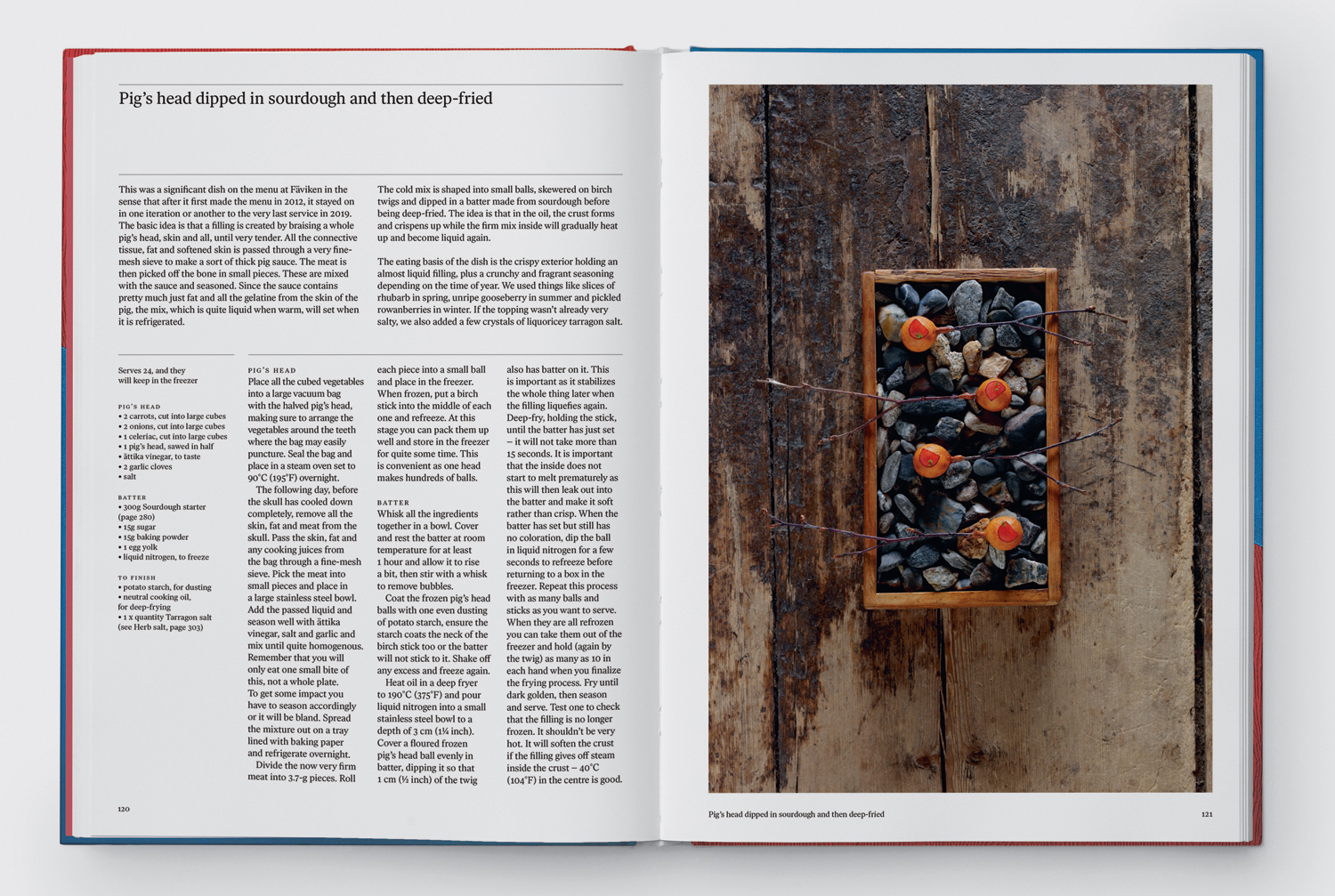

Magnus Nilsson’s new book, Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End, is a great read for anyone interested in food, creativity or the search for (and pitfalls associated with) true excellence. It details a complete list of dishes served at Fäviken in chronological order, and describes not only how a great many of them are cooked, but also how the chef and his brigade developed these remarkable creations.

However, the book goes beyond the usual scope of the average cookbook or chef’s monograph. In this new title, Magnus actually describes how he turned a remote Swedish hunting lodge into one of the world’s most highly praised restaurants, and in the process, developed from a little-known culinary professional into an internationally renowned star chef.

Of course, he didn’t do all this on his own; as with so many in his profession, Nilsson trained, worked alongside and learnt from his culinary forbears. As a result, his cookery is influenced by the dishes these earlier chefs made. And that debt of influence used to bother him.

“I used to get really irritated with myself when I saw obvious similarities between my cooking and that of the great chefs represented in my cooking DNA,” he admits in his new book. “Irritated enough that early on I scrapped many dishes before they came on the menu, and even some that were already on the menu, whenever I noticed similarities that seemed too strong.”

Unlike songs, books and films, few recipes are copyrighted. There are exceptions of course, (the Cronut® comes to mind) though in most cases, chefs aren’t going to court to dispute who came up with, say Scallop I skalet ur elden, cooked over burning juniper branches, or Marrow and heart, grilled bread and herb salt (to pick two examples from Nilsson’s book).

That doesn’t mean Nilsson didn’t beat himself up over his debts of influence during Fäviken’s early years. However, that changed when the chef encountered the culinary philosophy of French nouvelle cuisine pioneer Alain Senderens “a person I never worked for and whose restaurant I visited only once,” writes Nilsson.

“His thoughts about food were shaped – and were delivering fantastic experiences to diners – long before I was even born,” Nilsson goes on to explain. “His legacy (among many other things of course) informed the thinking and process of Alain Passard, who worked for Senderens as a chef but ultimately took over his restaurant L’Archestrate and turned it into his own, L’Arpege. L’Arpege is the restaurant in which Pascal Barbot worked as the head chef before he in turn opened his own place L’Astrance, where I worked for some formative years before opening Fäviken.”

Those links made Nilsson change his mind. The ideas weren’t appropriated; instead influence flowed down, like inherited traits in a family tree. “Each person in this lineage represents a distinct generation and adds a new layer to the cooking that followed, consciously or not,” Nilsson explains.

“It makes me warm inside when I see a photo of my food next to Pascal’s in some magazine or on Instagram,” he goes on to say. “I can immediately recognize the way we both intuitively use the lines of the food the same way to our advantage when we are plating. Or when I see an old article about Senderens in his heyday and realize for the first time that he used a combination of flavours that I am using too. And it makes me proud when I see subtle hints of my cooking DNA in the food of someone who used to work with me.”

Of course, Nilsson still still believes that stealing ideas is a problem in the culinary community. “There is a great difference between organically using small building blocks of experiences important to you, unconsciously scrambling them up in your mind and adapting the output to your preferences (this is not plagiarism), and extracting someone’s entire thought, technique or visual expression and then presenting it as your own original idea (this is definitely plagiarism),” he writes. “An even more common form of plagiarism occurs when people don’t explicitly claim credit for an idea but also don’t give credit, letting everyone just assume it’s their idea because of who they are. This leads to fewer restaurants representing a truly unique expression and more that do the same thing at almost the same time.”

Nilsson has never been overly upset by chefs - particularly young ones - working his recipes and techniques into their dishes, but, he admits, “seeing established chefs – well-paid superstars with decades of experience in lauded restaurants and Michelin stars – misappropriating others’ creativity and passing it off as their own on a regular basis, this makes me sad.”

What can be done about it? Well, perhaps some problem lies in the way reporters relate to chefs. “In the food world, many of those arbiters are more interested in accepting an invitation to get flown in for a free meal somewhere in order to gossip with their peers than they are in going out for themselves and getting to know chefs and restaurants outside of the circle of obvious suspects and finding out who truly has something new to offer to the world.”

If we could change that well-established formula, perhaps we could pick out creative excellence more accurately, Nilsson concludes. “I guess I just wish people running restaurants would be celebrated more for who they really are and what they really want to do,” he writes.

To learn more about Nilsson’s singular point-of-view, and to learn how to cook the recipes really, truly developed at Fäviken, order a copy of Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End, here.