Magnus Nilsson's Momentous Moments: The day he realised chefs could learn a lot from high fashion

They both command high prices, Nilsson believes haute couture has higher standards and a better work ethic than haute cuisine

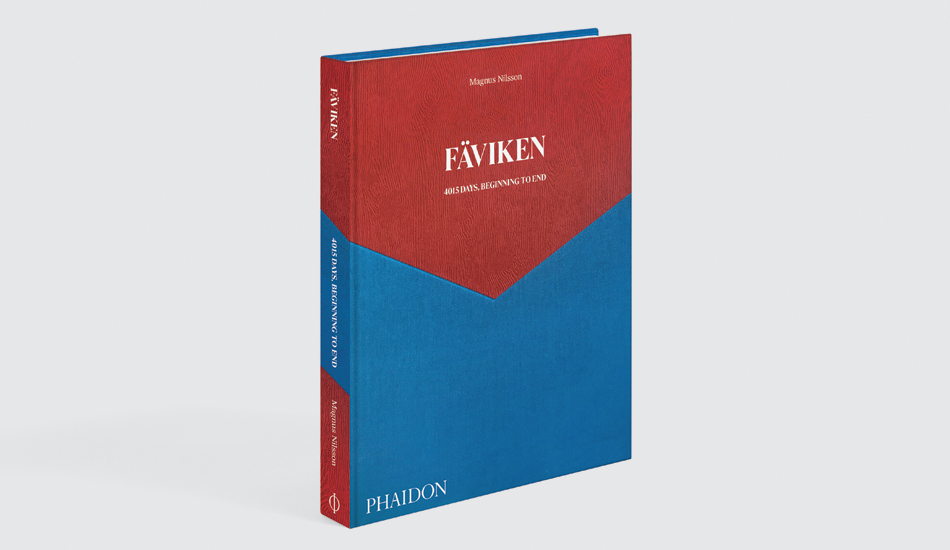

Magnus Nilsson’s new book, Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End, is a fantastically good read. It details a complete list of dishes served at Fäviken in chronological order, and describes not only how a great many of them are cooked, but also how the chef and his brigade developed these remarkable creations.

However, the book goes beyond the usual scope of the average cookbook or chef’s monograph. In this new title, Magnus actually describes how he turned a remote Swedish hunting lodge into one of the world’s most highly praised restaurants, and in the process, developed from a little-known culinary professional into an internationally renowned star chef. Some developments took time, while others came in a flash to the chef. Take the moment when Magnus was sitting in at the fold-down office table in the kitchen at Faviken when the news that Karl Lagerfeld had died flashed across the screen beside him.

As Nilsson recalls in the book, the death meant more to him, as he had briefly met the great designer when he was living in Paris during his early twenties. “I turned and saw a skinny man with white hair in a tight ponytail, dark rectangular sunglasses and clothes that could have come straight from the wardrobe of the very well-dressed head administrator of some sex dungeon establishment,” he recalls in our new book. “Black knee-high boots (very well polished), a black suit cut a bit like a uniform, plus vest, white shirt with a large, high collar and black tie. And, of course, leather gloves with the fingertips cut off.”

The meticulous side of Lagerfeld’s trade stuck with Nilsson, as news of the man’s death sank in. “Over the following few days it was all over newspapers, social media and pretty much everywhere else, and I kept seeing the words haute couture being used more often than usual,” he writes. “First it was mostly in articles about Lagerfeld himself and his life or work, but the days following also in other contexts, haute couture this, haute couture that, blah blah blah. Then it stopped again. But something about those two words made it impossible for me to stop thinking about them even after the rest of the world had moved on. What did they actually mean, haute, couture, Haute Couture? I mean, I knew when the expression was used and what it is, I am sure that most people do. But the more I thought about it, the less I was able to really define exactly what it meant. I typed Haute Couture into Wikipedia to get the following back: Haute couture (/ˌoʊt kuːˈtjʊər/; French pronunciation: [ot kuty ]; French for ‘high sewing’ or ‘high dressmaking’ or ‘high fashion’) is the creation of exclusive custom-fitted clothing. Haute couture is high-end fashion that is constructed by hand from start to finish, made from high-quality, expensive, often unusual fabric and sewn with extreme attention to detail and finished by the most experienced and capable sewers – often using time consuming, hand-executed techniques.”

“The realization hit me like a ton of butter (hand-churned from unpasteurized summer cream, well-aged and generously salted thank you very much) and I just sat there staring at the screen,” he writes. “This was exactly how I look upon what I do. EXACTLY. The phrase haute couture defines what I want to do in the kitchen in the most elegant and precise way.”

Of course, there is a very similar term to describe cookery too: haute couture. Though, as Magnus came to realise, the meanings are slightly different. “I typed haute cuisine into the Wiki search field too and what came back was reassuringly far from what excites me in cooking. Haute cuisine (French: literally ‘high cooking’ or grande cuisine is the cuisine of ‘high-level’ establishments, gourmet restaurants and luxury hotels.

“Haute cuisine is characterized by meticulous preparation and careful presentation of food, at a high price level. Some might say that those two definitions are virtually the same, but they are not, and the difference between them is important. I don’t think any ambitious contemporary chef (at least not the ones I know) worth their whites today would voluntarily call what they do haute cuisine based on the dull and dusty definitions above. The first puts the emphasis on the craft and the craftspeople, the rarity of the materials and the difficulty of the techniques used. The second puts the emphasis on price and the restaurants producing the food being perceived as fancy.”

And, in Nilsson’s opinion, that fancy perception isn’t always justified. In many high-end restaurants, “most of the work that goes into your dishes is done by the least experienced craftspeople, the interns, the trainees and the entry-level chef de parties,” he writes. “The truth, though, is that for quite some time now, most of the restaurants in the world that get the most attention (including my own) are quite similar in the way they work. They definitely do not produce an experience emphasizing craft and variation in expression based on rare and exceptional raw materials and skills. Most contemporary restaurants in our segment produce content which is developed by a creative team or a person who is more or less detached from the actual execution of the ideas.

That’s not too dissimilar: it’s not like the people designing haute couture sew it all themselves. And I believe that you can absolutely create amazing pieces of craft simply by catalyzing ideas and delegating them for other people to actually put into effect. But the similarities kind of end there. When the designer for a piece of high sewing gets an idea, it should ostensibly be executed by craftspeople at the very pinnacle of skill who will be able to execute exactly what the creator had in mind, flawlessly.”

Now that’s not quite true in the restaurant setting. “Food needs to be eaten right then and there and hospitality can only be enjoyed in the moment it is delivered. The waiter cannot approach in the middle of a $350 tasting menu just to say that the next dish is taking a bit longer than normal today, and they will be back in another hour or three when the kitchen feels that everything is optimal,” he explains. “Nor can the restaurant offer the news that the cook who is the world’s most skilled expert on cooking your chicken the exact way the designer/head chef intended is home sick today so unfortunately you have to come back another day if you want your main course.”

Of course, that’s doesn’t mean you couldn’t run a place that could meet these very high demands. “I am convinced that someone could run a restaurant that avoids these ridiculous scenarios but maintains the essence of haute couture,” he writes. “But it would take a team of extraordinary skill and a completely different way of looking at the process of sourcing produce. It would also take the absolute presence from the leader of that team to work. During every single service, he or she would have to be there, actually cooking, not just welcoming guests at the door, not just running the pass, but actually cooking. Not many chefs are willing to make a commitment like this for more than a few years in the very beginning of their career. It usually doesn’t take very long and not much success before the temptation to have more freedom to do other things becomes more important for most than what they set out to do from the beginning. Which was to cook,” Nilsson concludes. “But it does sound like a wonderful restaurant to eat in, doesn’t it?” We’re sure Karl would have approved.

To read more top table insights from one of the world’s most talented, experienced chefs, order a copy of Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End here.