INTERVIEW: Spirited photographer Andy Sewell talks cocktails, cables and fine art photography

The master of mixed-drinks photography explains how he created such perfect cocktail imagery for our new book

Spirited makes for a wonderful drinking companion. Subtitled, Cocktails from Around the World, the book not only includes recipes for hundreds of mixed drinks from around the globe; it also unpacks many of the fascinating stories behind these tasty and potent concoctions.

Yet the book is truly set apart by its crystal clear, stylishly executed photography. And for this, we have to thank Andy Sewell. This acclaimed British photographer is equally at home shooting images for fine art galleries, as he is photographing drinks for esteemed publications such as this one. Read on to discover how he approached Spirited, which art movements influenced his work, and the reasons why he likes to leave oh so subtle imperfections in his near-perfect images.

There are differing motivations when it comes to creating images of food and drink: one is to create a realistic depiction of the subject, and the other is to make it look as good - as appetising - as possible. How did you reconcile these two in these photographs? When making work in an art context I am looking for pictures that I don’t fully understand. That are seductive but that don’t resolve easily. As you say when making photographs for a commission like this there is still the desire to make a seductive picture but also one that conveys a certain amount of specific information. I’m using much of the same craft and approach as when taking any other picture but what I’m aiming towards is something more straightforwardly descriptive.

Have any of these images, or any aspect of working on this book, informed your fine art practice? Over the last few years I have been shooting a lot of commissions related to food in some way, sometimes behind the scenes with chefs or stories about how food is manufactured, fishing, farming, etc. It’s always a privilege to learn from people about what they do and how they live. Some of these experiences feed directly into my art practice others less so. With this shoot it was great to learn more about the history of different cocktails and how to make them. And of course to try some of them after we’d finished shooting!

In many instances, the photographs show light passing through transparent, or translucent objects. There's a venerable history of this sort of imagery in art, from the stained-glass windows of medieval Europe through to California's Light and Space movement. Did any of these precedents influence you when making these pictures? Light, the way it reflects off or passes through objects, is obviously essential to visual art. This is especially true of photography—the word literally means drawing (graphos) with light (photos). It’s something I’m always considering and when a photograph is as stripped back as these—a glass on a counter in a bar— it becomes even more present. I suppose a kind of stripped back minimalism is what many of the Light and Space artists were working with. I didn’t really consciously think about art historical precedents when making these pictures but of course these things are always there, largely unconsciously, informing how I take and select pictures.

There are plenty of urban legends describing how food stylists blast their display with hairdyers, etc. Were there any simple hacks used by you to improve a drink's look? I think most of these legends are true. But mostly they come from a time when these pictures were taken using very hot lights and with cameras that took a long time to set up. I approach photographing food or drink in the same way as I do anything else. I work relatively quickly and mostly with natural light. Where possible I want what’s in front of me to be the real thing, what would be served to eat or drink. I think it’s the imperfections in things that give them character, that make them come alive and hold our attention. In a way it’s these imperfections that I’m looking to find and to capture in a picture, so I don’t want to photograph some lacquered and perfect model. The same thing is true of retouching, often the impulse here is to digitally remove the very things that make a picture work.

Up until now you've largely produced landscape or documentary work. Was it hard to pivot towards what are essentially still lifes? I don’t really think in terms of genre when making pictures. You’re right that landscape is often a theme in my work, but the photographs are always a mix of what we might call landscape, portrait and still life. And what I’m really interested in when it comes to landscape is the relationship between the ideas we have about a place and what we find there. One of the things I love about walking around with a camera is the way it helps me to let go of some of my assumptions about things and notice what is in front of me. To disrupt the images that have formed in my head and loosen my grip a little on the categories I use to order and navigate the world.

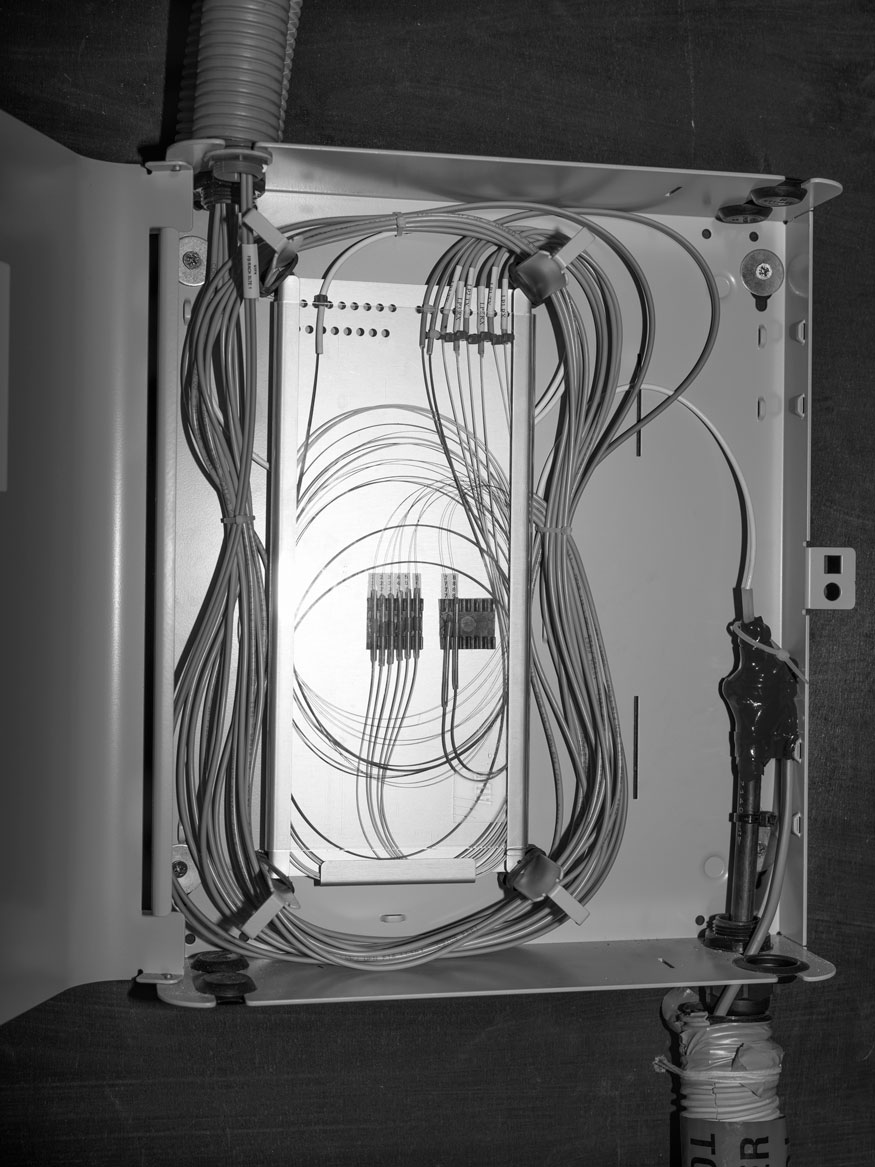

I guess what I’m trying to do is find pictures, in whichever genre works, that capture and convey this experience. For example, my first book The Heath is about the paradox of a place that managed to feel wild. The second Something Like a Nest explores the gap between the countryside as an idea, somewhere often imagined and depicted as an escape from modernity, and the messier, enmeshed landscape we find there. And my latest book Known and Strange Things Pass looks at the cables carrying the Internet across the Atlantic and coastal locations they link. Exploring, in these places where the digital network is concentrated, a literal and metaphorical entwining of worlds we think of as separate - the ocean and the Internet, the close and the distant, the physical and the virtual, what we think of as natural with the cultural and technological. This recent work, as well as landscape, portrait and still life, also has photographs taken while swimming in the sea and being pulled around in the waves.

You have a new show next year about the places along the Atlantic where Internet cables surface. It reminds us a little of Trevor Paglen. Could you tell us a bit about this? This work, Known and Strange Things Pass, is made in places where the Internet is concentrated. Where the fibres of the network come together, and almost everything we do online passes down a few impossibly narrow tubes, stretching along the seabed, connecting one continent to another. As you say Trevor Paglen has also photographed in these places, taking pictures of cables he found on the sea bed and using them to speak of communications choke points that have been tapped by security agencies.

In my work, as the critic Eugenie Shinkle has written, “the cables are only one thread in a web of analogy that explores what it means to be in the world at the present moment.” I photographed in the landing stations where the cables come up out of the water, and in places—the shore, the streets and in the ocean— beneath which the cables invisibly pass. I’m interested in how these vast, unknowable objects - the ocean and the internet - speak to each other, and to us? How do they relate, these things we think of as being completely separate, but that when we look closer, are literally and metaphorically enmeshed with each other. For me the work is a way of exploring feelings of embodiment and disembodiment in a world shaped by the digital network. It’s about touch and action at a distance, about relationships between the virtual and the physical, and between power and vulnerability, about the permeability of the boundaries we place between things and the fragility of what holds them together. The work has just been will be shown at Robert Morat Gallery in Berlin from January to March 2021 and at the V&A Museum in 2022.

To see Andy Sewell’s beautiful cocktail photographs and learn the stories behind the world’s most famous cocktails, order a copy of Spirited here.