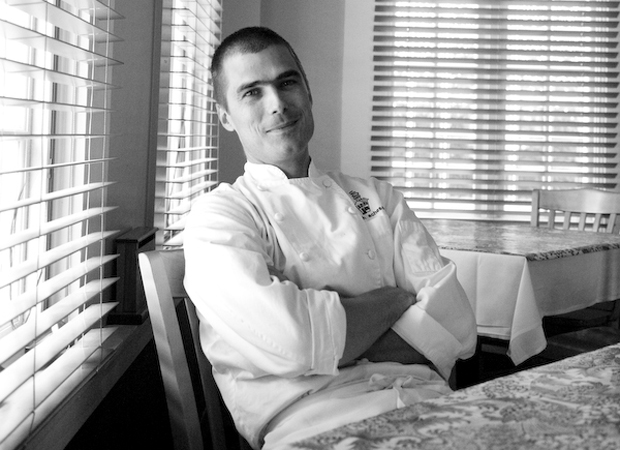

Coco chef close-up: Hugh Acheson

One of America's young rising stars explains why it's the old recipes that are his inspiration

Based in Athens, Georgia, in the US, Hugh Acheson’s style of cooking focuses on fresh, local ingredients and is characterised by contemporary twists on traditional recipes. He runs Five & Ten, the National and Gosford Wine in Athens, and has recently opened a new restaurant, Empire State South, which he describes as a homage to southern food, in Atlanta. He was selected by Mario Batali as one of the most significant young chefs working today for Coco, Phaidon's comprehensive book on who to watch in the culinary world today.

Q: You were selected by Mario Batali in the book Coco as one of the most significant chefs working today. What does it mean to be included in such a book?

It was definitely a big treat – and it was great exposure. I was probably the most plebeian cook of the bunch in that I don’t do fancified high-end food. We couldn’t have asked for a better mentor - Mario is such a skilled chef and business guy.

Q: How has your approach to cooking changed over the years since your inclusion in Coco?

We’ve been doing what we’re doing for a really long time so I don’t think we’ve changed much. If anything I think being included in the book was an encouragement not to change. We felt we were being recognised for what we do well and what we care about, and that because this was clearly pertinent to people we should stick with that.

Q: Which of the other chefs included in the book do you feel closest to?

Probably Donald Link and David Chang: independent restaurant owners who are just doing good food at all costs.

Q: Which recipe are you most proud of creating or re-inventing?

Recently we’ve been doing a lot of things with localised ingredients, so using boiled peanuts in hummus in place of chick peas for example, which is a sort of novel approach to things. Boiled peanuts are most commonly found in the South, particularly in Georgia. In terms of a particular dish, we do a southern twist on a bouillabaisse which we think is very interesting, called Frogmore Stew. This stew comes from the South Carolina low country and traditionally one wouldn’t eat the broth. We turned it upside down so that instead of using the broth as just the base, we made it into something you'd want to consume. We are not reinventing the wheel, it is just a reverence to the local stuff that is coming through the back door and we're keeping it pretty simple and straightforward.

Q: Good food and cooking is a mixture of many things, what elements do you feel underpin good cooking?

It’s about local, it’s about patience and it’s about skill. And salt.

Q: Can you tell me about your approach to cooking and creating new recipes? Do you start from the same point or do different dishes always require a different approach?

We’re a place that wants to give a nod to the past so we read a lot of old cookbooks. The Time Life series on cooking that was so great. Even simple American cookbooks like Fanny Farmer it is such a tome that if I look through there I can find anything and just take an idea from it and rework it into something using what is available now that is more fresh and current. Other times its just a matter of taking something as a concept and just reworking it, and it's just a eureka moment of food.

Q: How has the idea of sustainability become more important in your cooking?

I’ve always thought that local should come first. I would rather buy conventionally-farmed local strawberries than organic strawberries from California. I feel that if I buy local I can change the farmers’ habits over time. I can advise them that it is better for the economy and for the environment to farm organically; through buying power and marketing we can nudge them in that direction. We’re much more sustainable if we don’t use all this fuel to transport everything. Sustainability is such a minefield of a word, but I think if you cook in the style or at the level that everyone who is included in Coco cooks at, then you are going to beget sustainability. Quality of ingredients of that stature are generally sustainable.

Q: Who do you most admire in the world of cooking today?

Mario [Batali] would definitely be up there. He is an uber-skilled chef. Even with the shorts and the orange crocs and the multiple restaurants, he can still cook. And he doesn’t create many failures in restaurants; he’s got, like, 18 success stories. I also like Joël Robuchon, somebody who has been such a grandfather of French cooking for so long, and is still doing it so well.

Q: Who would you most like to cook for and why?

Thomas Pinchon - elusive writers would be cool to chat with.

Q: Where do you like to eat on a night out?

We like Vietnamese food and Japanese food. I like to eat what I don’t cook, not because I would sit down and be like ‘I could do better than that’ but because I like food that is new; there’s always something exciting in it for me.

Q: What’s your advice for aspiring chefs?

Don’t do a cooking course! Cookery school has been made fashionable and people are led to believe that it’s economically viable, but it’s really expensive, and the problem is that you come out of it and you’re making the same as someone who never went to cooking school. I’d much rather that someone took $40,000 and travelled for a year and worked in ten different restaurants for a month. If someone got that kind of experience and said they wanted to work with me I’d be much more apt to hire them.

Q: What do you wish you’d known when you were starting out?

I would have loved to have known that you need to know how to live cheaply, you need to be smart about how you’re doing it and you have to work a lot. As much as TV and beautiful magazine photos make it out to be, this is not a glamorous job. It’s inordinately enjoyable, but it is not easy.

Q: What’s your view of today’s restaurant community and the state of the food industry at large?

I think it’s really interesting. The last recession was almost a correction for the world, so we’ll see what impact this one is going to have. I think that the way people are eating is changing; people are becoming more conscious as to what’s on their plate and where it came from, and the number of hands that touched it before it got there. Beef quality for example is getting better. I think farmers are going away from genetically modified food, though the GM issue is still divisive. There’s a lot of people for whom it wouldn’t enter the sphere of what matters. But there’s also lot of people who are very conscious about it and there’s a lot out there on the subject.

Q: How do you see the future of cooking?

It will be interesting to see what will happen. I think fine dining will maybe fall by the wayside a little bit. I think food is going through a time of schism - there are definitely two camps emerging, one of which is finding new ways to create foam, and the other is banishing foams off to the sidelines and wanting to do more traditionalist stuff. I think you’re going to see the price of local food come down. It’s no longer that precious little commodity. In Athens, Georgia, and Atlanta there are umpteen more organic farm options locally than there were before. Eight years ago we were the only people who had local Nantes carrots, but now they’re sort of ubiquitous. That kind of thing is going to have a huge impact on how we eat. We’re going back to a time when we didn’t eat so many manufactured and embellished foods.

Hugh Acheson, thankyou