Phaidon Introductions: Thierry-Maxime Loriot on Mugler’s early years

The curator of the new Mugler show takes us from the designer’s childhood through to his first big break

The designer Thierry Mugler’s creations are so futuristic, it’s hard to believe the designer, who was born in 1948, began his career before almost all of his contemporaries, and, what’s more, came to fashion after pursuing a highly successful career in a completely different field.

Here’s how Thierry-Maxime Loriot, curator of the new Thierry Mugler exhibition, and co-author of our accompanying book, Thierry Mugler: Couturissime, puts it, in that title’s opening pages.

“The son of the senior physician at the Vittel spa and a mother who was, in his words, an ‘artist, comedienne and tragedienne, diva and superstar’—a flamboyant five-foot-nine redhead with the shoulders of a swimmer, his first muse and source of inspiration—Thierry Mugler grew up in both a large, Haussmann-style apartment in Strasbourg and a middleclass house in Vittel,” writes Loriot.

“It was a childhood spent in the 'Middle Ages in Strasbourg’ and the ‘1900s in Vittel’” never in the era in which he actually lived. He whiled away the days in the forests of the low mountains of the Vosges. Mugler had a very authoritarian, old-style German upbringing. In a family that was not very affectionate, he was met with a complete lack of understanding.

“’When I was a kid, I was totally uninterested in school; I really didn’t like the other children, although I found the teachers fascinating,’ he recalls. ‘I was very unhappy and would run away. I was incapable of following the rules.’ The windows of the high school he attended, the Lycée Fustel de Coulanges, looked out on Strasbourg’s Gothic Notre-Dame Cathedral, just steps away from the Palais Rohan museum; it was conducive to his daydreaming. Thinking the teachers badly dressed, he made changes to their outfits in his imagination.

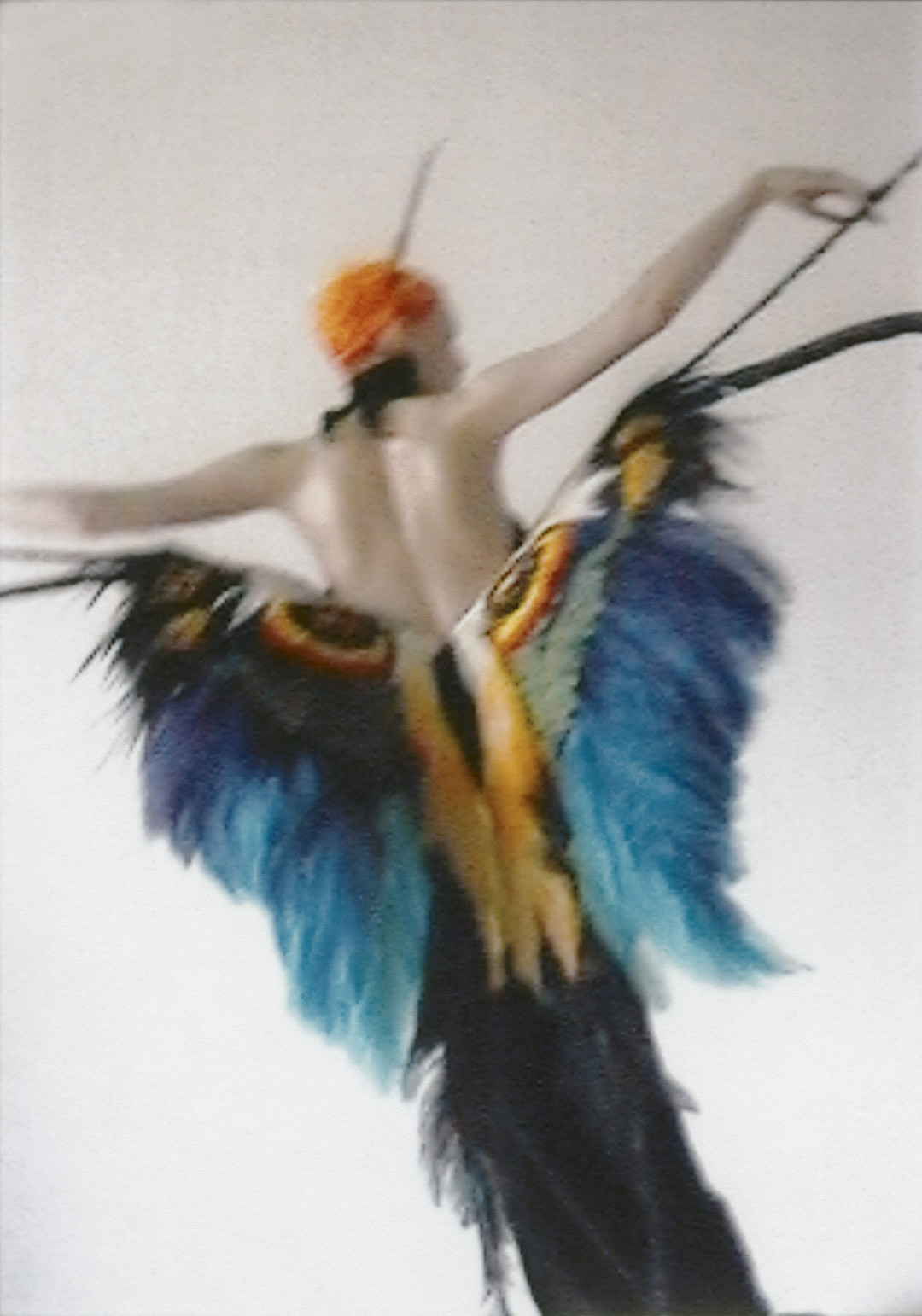

“In Vittel, a wonderful woman who dressed all the children for the spa town’s annual fête and collected costumes from local productions of Donkey Skin or Cinderella, had him make the same out of crepe paper, tarlatan and silver colored lace. In Strasbourg, there was Mademoiselle Aubenas, a woman of a certain age who took him under her wing and sometimes looked after him at her home. She took children to the museum and the movies, expanding their horizons with a complete freedom. It was she who persuaded Mugler’s mother to enroll him in dance classes. Young Thierry’s idols were the Cuban actress Chelo Alonso and her compatriot, the singer Celia Cruz, as well as the Peruvian songstress Yma Sumac.

“’I always had a project on the go: I was creating a new play, costumes for the characters, drawing, writing songs . . . I was no ordinary child, and people often avoided me. It was truly psychotic. I often had the feeling I was crazy. My parents constantly threatened to send me to a reformatory. There was a mental hospital on the way to school and I made sure not to go anywhere near it, for fear they’d lock me up!’ remembers Mugler.

“His mother considered the way she looked and her couture wardrobe a priority: always stunning, she was a mix of Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable incarnate. She did her shopping at the local market, young Thierry in tow, shod in scarlet-red, high-heeled boots and dressed in a long lynx coat. ‘My parents lived out a passionate love affair—a very destructive one—behind a facade of hypocrisy, finally divorcing when they were sixty. I remember, when I was eight or nine, finding my mother with slit wrists. She was a great tragic actress, and it was quite dramatic. It wasn’t a stable environment, which explains why I left home at the age of fourteen. It was the start of my dream, but I also wanted to get away, no matter the cost,’ relates the designer.

“Mugler, who had began evening classes in classical dance when he was nine, received his first contract with the Ballet de l’Opéra national du Rhin at fourteen. It was a full-time learning experience. He was classed a character dancer and was given villain, pirate, clown and mime roles, but never those of the prince, since he was too tall. ‘It is a vocation. It’s all-consuming, a calling, an art of glorification. You have to push beyond your limits, use your pain to make something beautiful and true out of it. It was extremely physical. I needed that,’ says the couturier. He toured with the company in Europe and danced Swan Lake for close to six years, but returned to Strasbourg at the age of eighteen to study design at the city’s school of decorative arts and learn about stagecraft, advertising and display. Dance had taught him about ‘bearing, how a garment should be structured, the importance of the carriage of the head and shoulders, pace and presence,’ he states, adding that ‘dance and fashion have a lot in common: fashion is a production, and the runway gives you the opportunity to put on a real show.’

“In 1967, following a move to Paris in search of a more creative outlet, he went on two significant trips. First, he went with a friend to New York, then set off to explore the United States and Mexico. He visited the iconic locations of Andy Warhol’s films, like the legendary Tropicana Motel in West Hollywood, where the American Pop artist’s Heat would be shot in 1972, and the Chateau Marmont hotel, where Mugler would live part of the time for nearly thirty years in Suite 54, above the one occupied by Helmut and June Newton.

"After meeting Savitry Nair, a dancer who had created Indian ballets for Maurice Béjart and Pina Bausch, in Paris, Mugler next traveled to India for three months to learn Kathakali, a type of dance-drama from the southern state of Kerala that is a mix of mime, dance and martial arts. He let his hair grow, ‘before the Beatles,’ as he points out. On his return he auditioned for Béjart, whom at the time he considered ‘a dance god.’ He was offered a place, but in the end turned it down, as it meant he would have had to move to Brussels; he was hardly thrilled by the prospect and even less by that of performing in Swan Lake, the Roi d’Yvetot, or Mam’zelle Angot for the umpteenth time given the all-too-few contemporary works.

“’Fashion came along quite naturally,’ tells Mugler. ‘As a child, nothing suited me in the way of clothes, and I was already cobbling together my own, which were an integral part of my search for an identity.’ It was a need, indeed a necessity, to assert himself that was rooted in his opposition to authority, and the utter loneliness of his childhood and adolescence. People were always pointing their fingers at him, even in the ballet, and yet the need to be different drove him, like that of enjoying himself and showing his worth.

“When he arrived in pre-May 1968 Paris, through a friend Mugler met someone who sold sketches of fashion designs. He did not have a clue as to what design actually was as a profession, but he knew he could do the same thing. He was fascinated by Dorothée Bis and Gudule, a boutique located on the Rue de Buci, in Paris’s 6th arrondissement, which in his opinion was the ultimate of cool. ‘In one night I made thirty sketches to go and sell to them,’ he remembers. ‘At the time, fashion houses like Cacharel and Dorothée Bis didn’t always have designers affiliated with their label. They bought from young talents with ideas. I called them all, and they all bought my designs. The person I desperately wanted to meet was Eva Picovski, from Gudule. She had opened that boutique in a former butcher’s shop, something no one had ever done. Her sales girls wore black lipstick and nail polish. My mother collected fur coats, and it just so happened that her furrier knew a friend of Madame Picovski’s.’

“It turned out that the friend was in fact Eva Picovski’s cousin. When the young Mugler went to see him in his atelier in Le Sentier, Paris’s garment district, the man declared, speaking about his design sketches, ‘Eva is not going to like these.’ Mugler was completely taken aback: Madame Picovski’s first name wasn’t Gudule, but Eva! The precious bit of information enabled him to find her telephone number, give her a call to introduce himself . . . and also tell her that her cousin recommended she see him as soon as possible, as the man thought it would be ‘a genuine encounter.’ Eva Picovski gave him an appointment for the next day. ‘At that time,’ relates Mugler, ‘we’d go out to the Cherry Lane club on the Rue des Ciseaux. The looks I wore followed certain themes, not what was in fashion—intergalactic superhero, Renaissance or a kind of neo-Middle Ages but Pop style with red-cuffed musketeer boots, abbreviated bell bottoms, a real black felt Quaker hat, a white lace choirboy’s surplice and a wide belt. Eva didn’t even look at my drawings. She immediately entrusted me with designing her windows and then, a few weeks later, garments, which became very popular.’”

For more on Mugler’s early days, later success, and enduring appeal, order a copy of Thierry Mugler: Couturissime here.