All you need to know about Omer Arbel

Our new book outlines the unique processes and singular outlook of one of the world’s greatest design polymaths

No one makes things quite like Omer Arbel. Consider this recipe for creating delicate glassworks (given the number 108 within his personal design log).

“Javelins are fired into the sky during a thunderstorm, with a conductive cable leading the electrical charge from a captured lightning bolt to a large insulated canister. The canister contains a mix of mineral and metal powders designed to produce phenomenologically interesting results when fused. The heat generated by the electrical charge fuses the powders into solid objects conforming to Lichtenburg dendritic patterns [the shape of a branching electrical discharge] (in nature known as fulgurites). Thus, each 108 is a signature or shadow of a specific bolt of lightning.”

In an age of showy self-expression and mass production, Arbel stands apart, as a hard-to-define design polymath. A few things are assured, of course. The Israeli-born, Vancouver-based designer, artist and architect created the Olympic and Paralympic Medals for the 2010 winter games. He is also the co-founder of the acclaimed lighting company, Bocci. He also numbers his works, rather than names them, allotting a number that corresponds with the order in which it is created. Our new Omer Arbel monograph is dedicated to this celebrated multi-disciplinary designer and master of sculptural lighting.

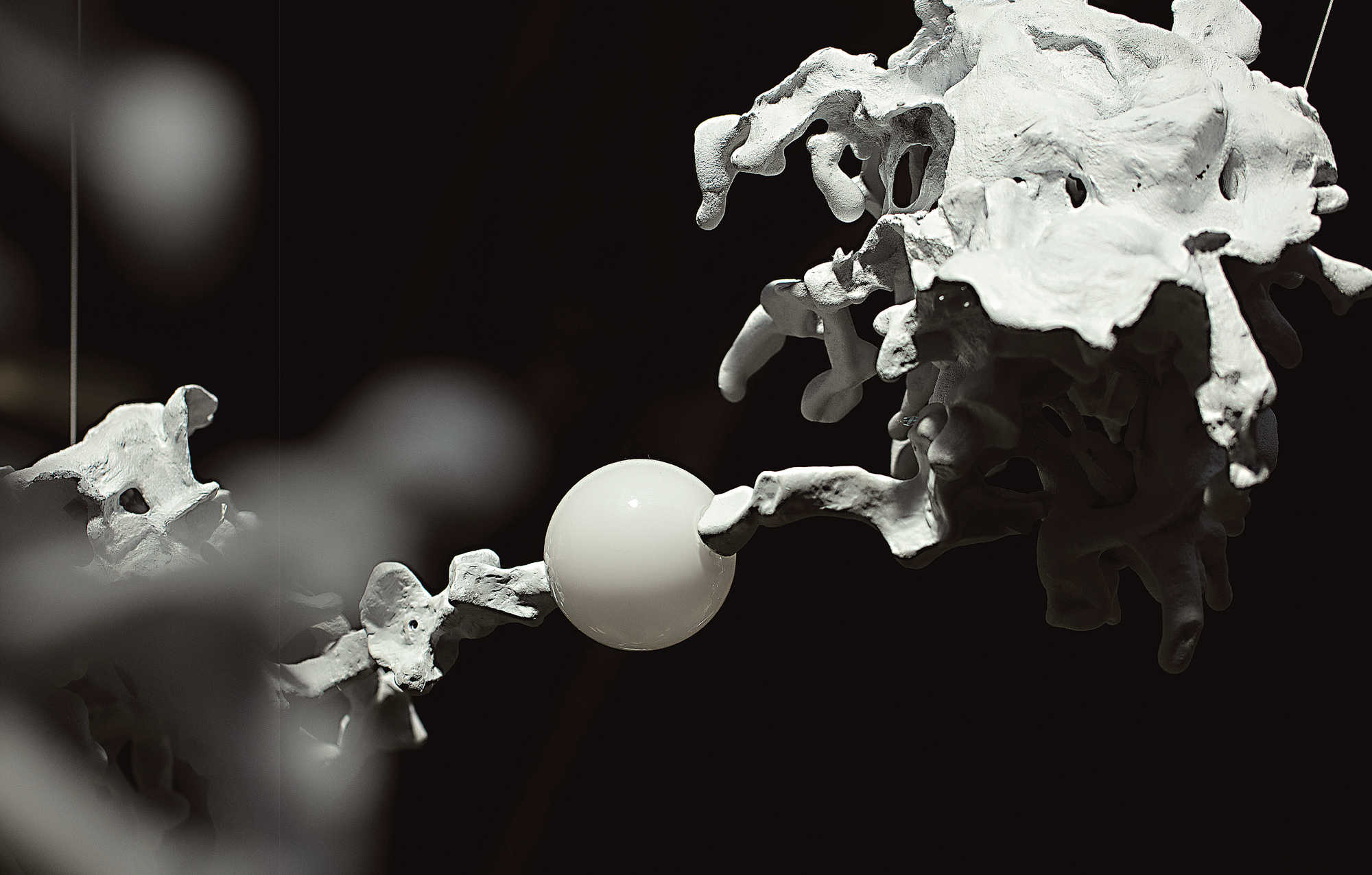

Arbel's techniques, ambitions, and finished works are quite unlike anything else being made today. The work of Omer Arbel Office moves fluidly between the fields of design, architecture, sculpture, and invention. His own businesses are divided up, with a separate commercial platform for lighting and glassware (Bocci) and a research and development-oriented product design studio (OAO Works), in addition to his architectural office. Yet projects within one can overflow from one to the other, calling into question both Arbel’s role, and the function of the finished product.

Take Arbel’s 64th design for a wax candle, for instance. “64 is a candle made by pouring molten wax into a bucket of broken ice. The bucket is then rotated at high speed. As the wax penetrates the negative space between the ice chunks, it cools and solidifies. Once it has set, the ice is allowed to melt, leaving behind delicate filigree.”

Or this, Arbel’s 28th design, a glass globe. “A bubble of glass is blown conventionally (air going into the glass), and is allowed to cool; heat is applied locally to a patch on the outside of the now stiff, cold sphere, then very hot glass of another colour is dropped into the hot patch; the direction of airflow is reversed (air pulling out of the glass), creating a vacuum that only the hot glass can respond to. A controlled implosion occurs, giving the piece its distinctive form.”

There are plenty of others in our new book, such as the jagged metallic forms, (no. 44 in his design canon) first made by pouring molten metal into a canister of broken sand molds; or no.84, consisting of two concentric glass globes, separated by a copper mesh: “Air pushing outward from the center forces the glass of the inner bubble through the mesh and into the outer bubble, with the mesh pattern constricting the expansion and achieving a repeated pillowing or ghosting form.”

Each form is fascinating, and each process is both a signature work, and an oddly impersonal process for a designer whose process, as the author and curator Glenn Adamson puts it in our new book, “can be described as parametric.”

“Rather than setting out a defined objective—one that could be drawn and executed—Arbel instead devises a set of constraints within which the making happens,” Adamson explains. “In effect, his designs are more like verbs than nouns, operations that can be run on different materials in different contexts. The core ‘recipe’ produces something new every time. Though infinite in variation, every potential outcome, every occurrence, is considered equally valid as an expression of the design. The parameters that Arbel defines may be physical, technical, dimensional, or atmospheric, depending on the procedures involved.”

Our new monograph mirrors this state of creative flux. The book brings together twenty-two compelling projects — from lighting works for Bocci to furniture and standalone homes — to reveal Arbel's radical design ethos, which is rooted in material experimentation and collaboration. Organized by four thematic chapters and richly illustrated with beautiful product photography interwoven with preparatory drawings and ephemera, this book provides unique insight into Arbel's highly diverse practice.

Texts describing the pieces on show lie next to excerpts from a wide array of other writers such as the godfather of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud; the novelist Vladimir Nabokov; the land artist, Robert Smithson; and the sci-fi writer, Ursula K. Le Guin.

These lie alongside explanatory passages, describing Arbel’s personal and professional development, as well as his role as a master creative in our late, great age.

“His inventive use of hyper‑complexity demonstrates that it need not be a barrier to comprehension. Information overload can itself be channeled and shaped into a generative force,” writes Adamson. “It is a demanding way of approaching the job—one that permanently defers job description itself—but extraordinary in its vast potential. So, where is Arbel going? Even he cannot say for certain. This Is the power of parametrics. It defines a field of action, but everything still remains in play.”

To find out more about that singular interplay, and this singular design player, order a copy of our Omer Arbel book here.