The postmodern palace fit for a Queen

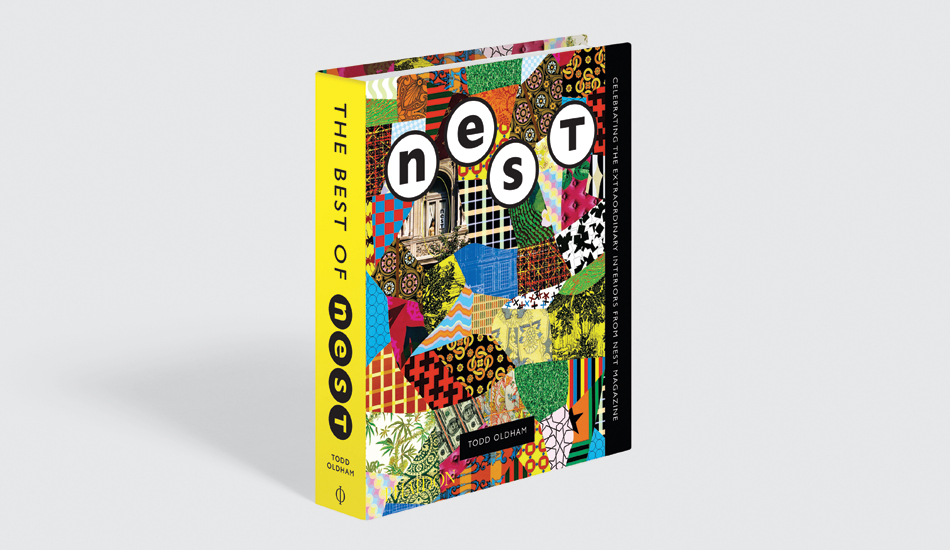

Our new book, The Best of Nest, showcases the wild side of interior design, including one very well known royal residence

Nest magazine always sought out the wilder side of interior design. The brainchild of artist and designer Joe Holtzman, Nest was published from 1997 to 2004, and during its run, strongly eschewed the conventionally beautiful luxury interiors of other magazines and instead featured non-traditional, exceptional, and unusual environments.

Our new bookThe Best of Nest, created by master bookmaker Todd Oldham, reproduces pages from the magazine, and features plenty of such settings, including Liberace’s house, a Mexican prison, and a pad in Harlem fashioned from old Coca-Cola crates. They’re all wonderful in their own way, but one interior stands out as being both incredibly well-known and almost entirely overlooked.

In the issue published in the summer of 2002, the author and design historian Pat Kirkham wrote about Buckingham Palace. Like so many Brits, Kirkham was familiar, if not entirely enamoured with the white, wedding cake of a building, which was heavily updated in the early eighteenth century by George IV and his architect John Nash.

“One of my fantasies then, about what I would do if I were queen, centred on relocating the breathtakingly exotic Brighton Pavilion (which George IV created before he was king, also with Nash) or the picturesque Windsor Castle (remodelled by George IV, with Sir Jeffry Wyatville as architect) to central London,” wrote Kirkham in that issue, which is reproduced in The Best of Nest.

Buckingham Palace was closed to the public during Kirkham’s childhood; she first visited in a professional capacity in 1972, and agreed with the prevailing opinion of the time, that the interiors were as overblown as the exterior was pedestrian. However, a later visit, in 2001, once the palace had been opened to the public, made her change her mind.

“The sumptuous, superabundant, heavy, and at times almost baroque version of eclecticism, wilful variety, density and intensity of decoration and gilding, went largely unappreciated at the time when anti decorative Modernist design still reigned supreme,” she writes.

Closely related to Modernist preferences for simplicity and restraint was the widespread veneration for the lighter, more elegant forms of eighteenth-century Neoclassicism that play only a minor rule at Buckingham Palace,” Kirkham goes on. “Today, when nothing is considered too eclectic and there is not top to grove over, the surfeit of decoration and free plundering of sources – from France under Louis XVI and Napoleon to Renaissance Italy and eighteenth-century Britain (particularly the designs of Robert Adam), with touches of the Rococo and Baroque thrown in for good measure – make the place a postmodern paradise.”

Viewing the royal residence as a po-mo masterpiece might be a little controversial; after all, the future King, Prince Charles, is a vocal critic of postmodernism. But, ruffling a few feathers was very much what Nest was all about. To see more from this wonderful magazine, order a copy The Best of Nest here.