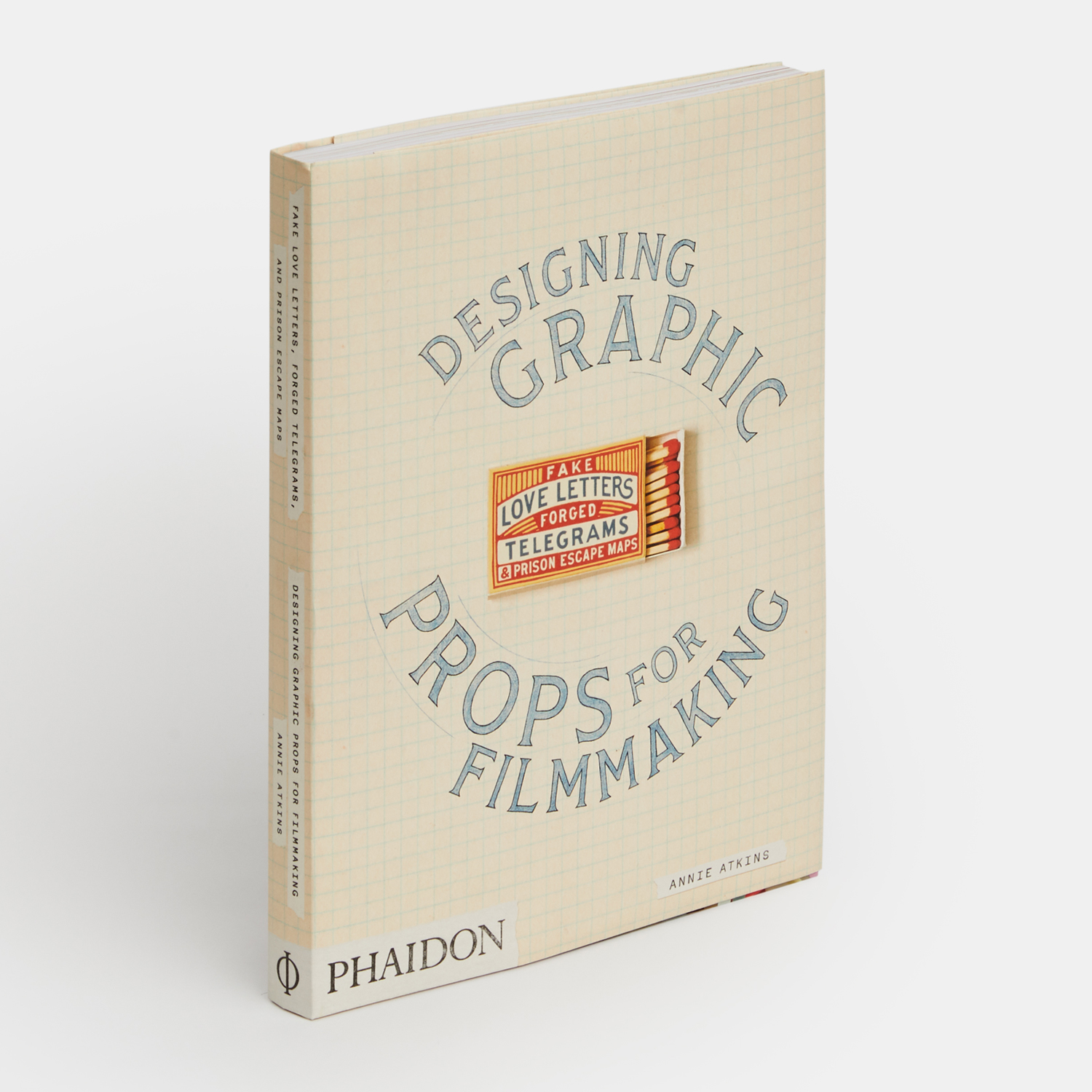

All you need to know about Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps: Designing Graphic Props for Filmmaking

The graphic prop designer behind Bridge of Spies, The Grand Budapest Hotel and Isle of Dogs lets us all in on the magic she helps create

How should the world look in the movies? It’s a question Annie Atkins answers in her beautiful, informative new book, Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps: Designing Graphic Props for Filmmaking. Aktins, who has made crafty, fantastical, yet entirely plausible graphic props for Steven Spielberg's Bridge of Spies, Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel and Isle of Dogs, and Todd Haynes's Wonderstruck, among other Hollywood films, is a cinematic insider. Yet she’s also a movie buff, and in her introduction, recalls one formative film from her youth.

In the 1998 movie, Big, thirteen-year-old Josh Baskin comes across the antique fortune-telling machine Zoltar, and he wishes he were a grown-up. The glass boxed, mechanical genie “growls, his eyes flash, and—despite Josh noticing that Zoltar’s cable isn’t actually plugged in— a small printed card shoots out of the dispenser: ‘Zoltar Speaks!’ On the reverse: ‘Your Wish is Granted,’” Recalls Atkins. “Exit the young Josh, who has transformed into a thirty-year-old Tom Hanks overnight, his life now unimaginably changed forever.”

This isn’t the only trick Zoltar has up its sleeve. The arcade genie looked so convincing in the film, many believed it existed in the outside world. “Perhaps Zoltar was a real arcade machine before the film was scripted?” Aktins wonders. No, the original prop was a new creation, made by the film’s set decorators George DeTitta and Susan Bode-Tyson remember. Yet many Zoltars have been constructed since, and it has now become a carnival staple.

Atkins’ own work may not have received quite the same level of tribute - yet - but the lengths she goes to, in order to make design objects with dramatic power and period evocation, are worthy of a movie or two themselves. Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps features hundreds of Atkins creations, including the protest placards from Isle of Dogs, manuscripts from The Tudors, the passports from Bridge of Spies, and the Mendl’s cake boxes from The Grand Budapest Hotel.

These beautiful, idiosyncratic works are a joy in themselves; As Grand Budapest Hotel star, Jeff Goldblum, puts it in his foreword to the book, "Annie coaxes the transendental into a meat-and-potatoes emotional logic."

Yet Aktins’ new book lies also reveals the tales behind these contemporary cinema design classics. Many of the tales are worthy of feature-length treatment in themselves. Consider the unexpected rare, naturally aged, unmarked 1940s paper, Atkins bought from a man in Riga, Latvia named Janis Linde.

“Linde had found his collection of old paper almost twenty years ago, when he was renovating the small garden house at his family home,” Atkins explains. “He’d noticed that one of the building’s outer walls was much thicker than the others, and when he knocked it down, he found a secret hollow filled with stacks upon stacks of packages, all carefully wrapped in large sheets of wartime black-out paper or windows. Inside each package was reams of unused paper—lined paper, graph paper, blotting paper, music manuscript paper—in near pristine condition.”

Linde’s great-grandfather had run a stationery business Riga, and, forewarned about Soviet forces seizing privately owned assets, had literally walled off his stash from the Reds. Atkins bought a consignment.

Discover how Aktins’ favours wooden-handled rubber stamps to make many of her hand-printed posters, bills and other documents, and often employs extras, on set, to do a little of the work for her. “One prop master I worked for pointed out that they can be handy for use in action, when background extras play hotel receptionists or office clerks,” she writes. “Extras always need something to do with their hands, to stop them from slumping over like zombies by the end of a long shooting day—and the wooden handle doesn’t date a stamp like plastic can.”

Learn of the problems associated with having a Tudor character write a convincing letter on screen. Aktins and co often had to rely on skilled ‘hand doubles’, adept in 16th century penmanship, to inscribe these works. The Tudors’ fourth season opened with “a close-up of the French Ambassador Eustace Chapuys writing home with the latest gossip from court,” she explains. “The hot summer’s day was illustrated in the script by the beads of sweat rolling down Chapuys’s forehead and onto the letter in front of him. In this instance (our summer might have been a good one but it wasn’t that good), professional calligrapher Gareth Colgan had to work with a prop man standing above him on a stepladder, dropping water from a pipette as if it were sweat falling from his brow.”

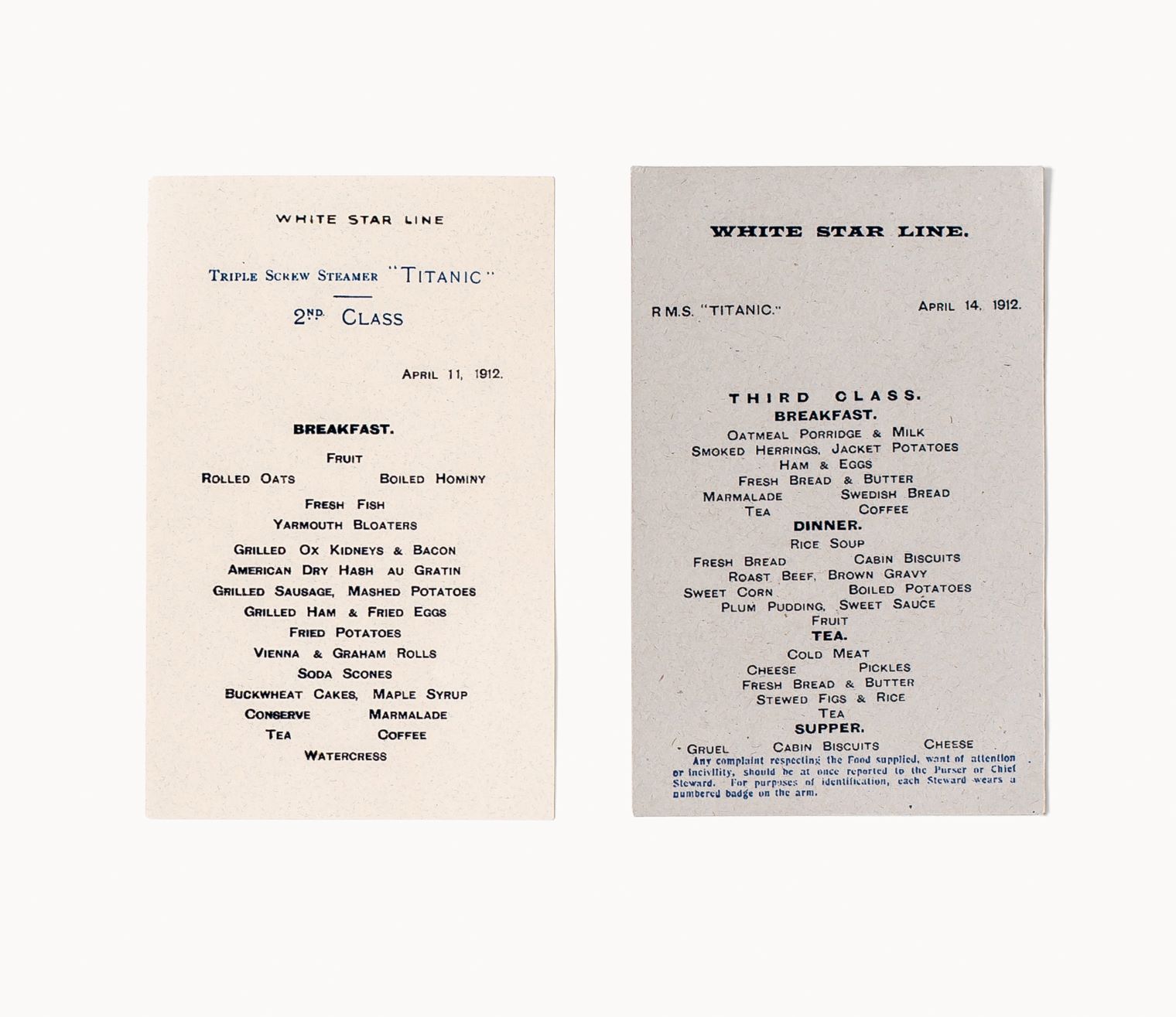

Aktins’ new book not only features many of the beautiful designs that made it on to the silver screen, but also plenty of inspirational items from her own collection, including English paper milk bottle tops, Egyptian cinema tickets, and a German girl’s journal from the 1920s.

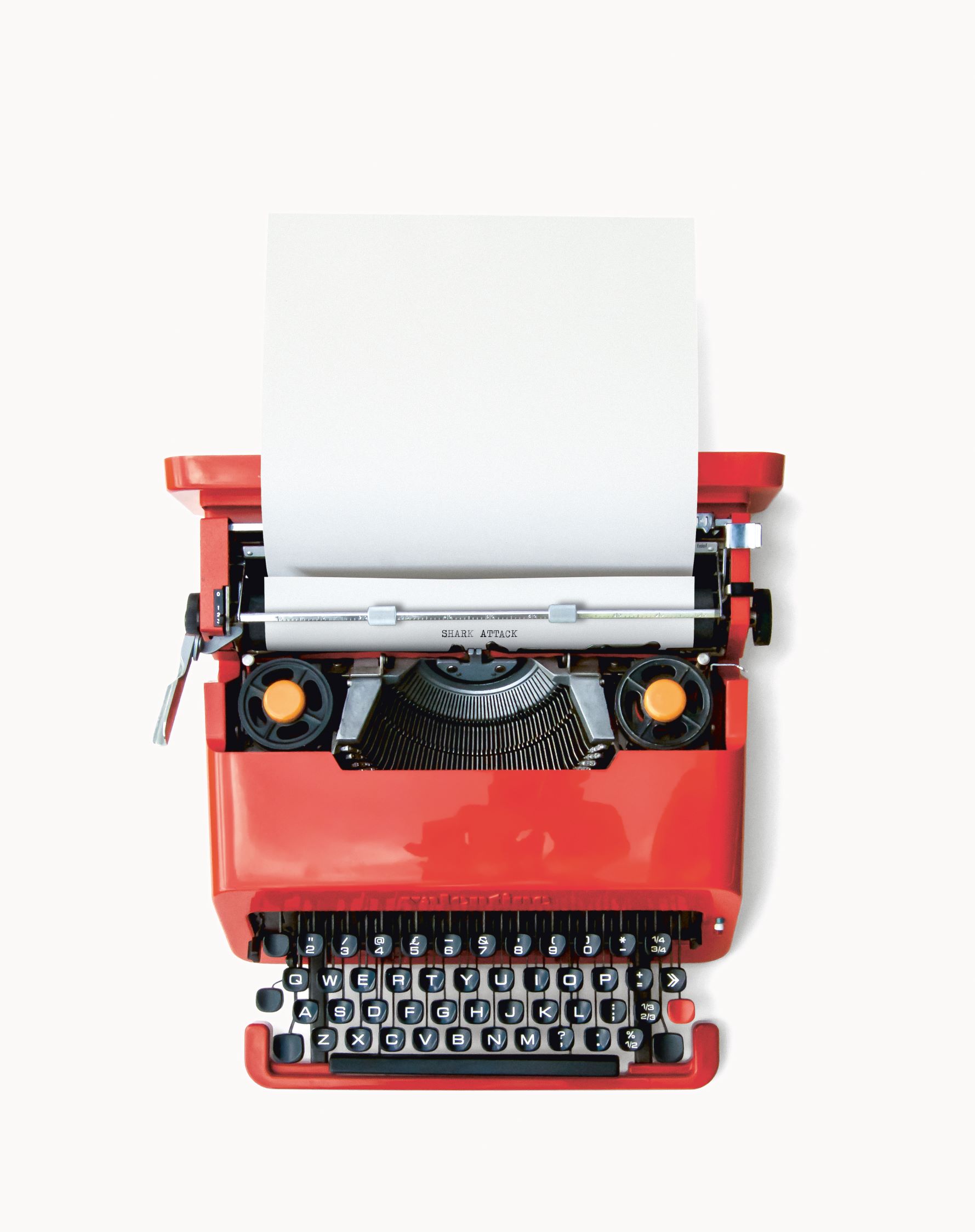

The author also features many practical tips and details of her own tools and methods, including examples of different ways to stain paper, photos of her favoured old-fashion typewriters and fake blood advice.

Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps, is a delightful guide for any amateur or professional prop maker; it could well give many commercial graphic designers good reason to break with existing habits, and try out antique and home-spun illustration methods. Movie lovers will also appreciate many movies more fully, having learned how Aktins makes such convincing, evocative props, and gallery goers will appreciate the sumptuous, visual treats held within these pages. To find out more, see the book in great detail, and order your copy, go here.