Soviet Space Dreams: It's Not Rocket Science (Actually, It Is)

How the reclusive rocket scientist, mathematician and writer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky shaped the USSR's space race

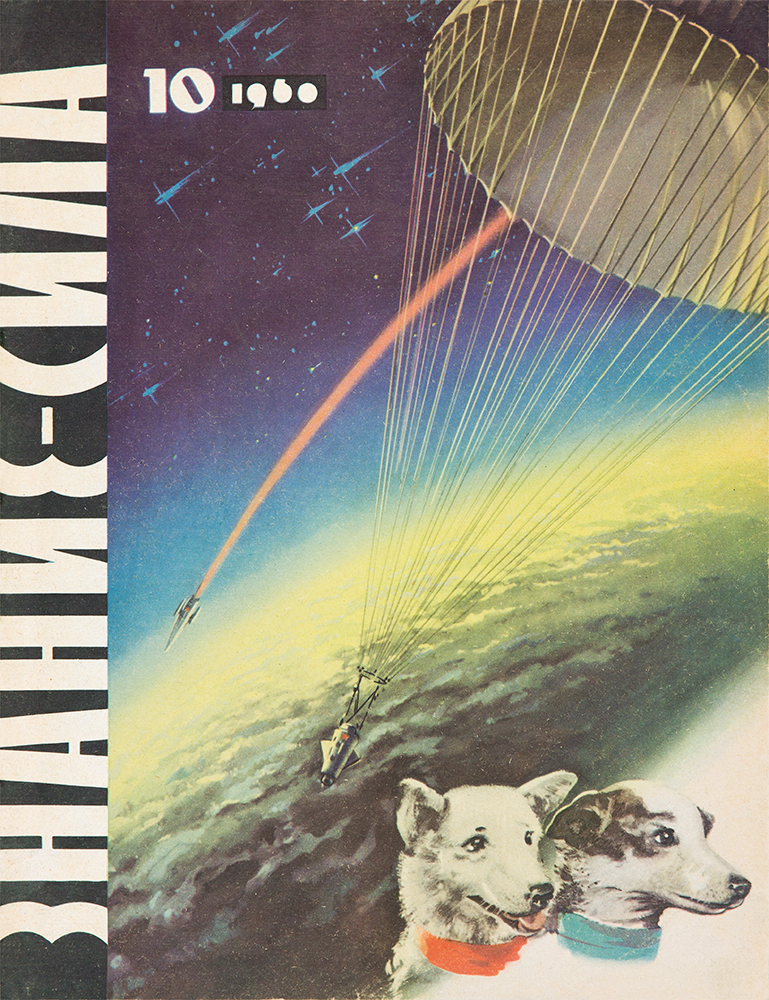

As our new book Soviet Space Graphics: Cosmic Visions of the USSR notes, the Russians really were rocket pioneers. They put the first dog, the first human, the first woman, and the first two- and three-man crews into space; carried out the first spacewalk; created the first spy and communication satellites; and launched crafts towards Venus, the Moon, and Mars.

And despite what Herculean efforts might have been going on behind the scenes, to the public at least, they made it all look rather easy. This is because at the outset of the Russian Revolution, the authorities wanted to make the achievements of science, industry and culture accessible to the general population.

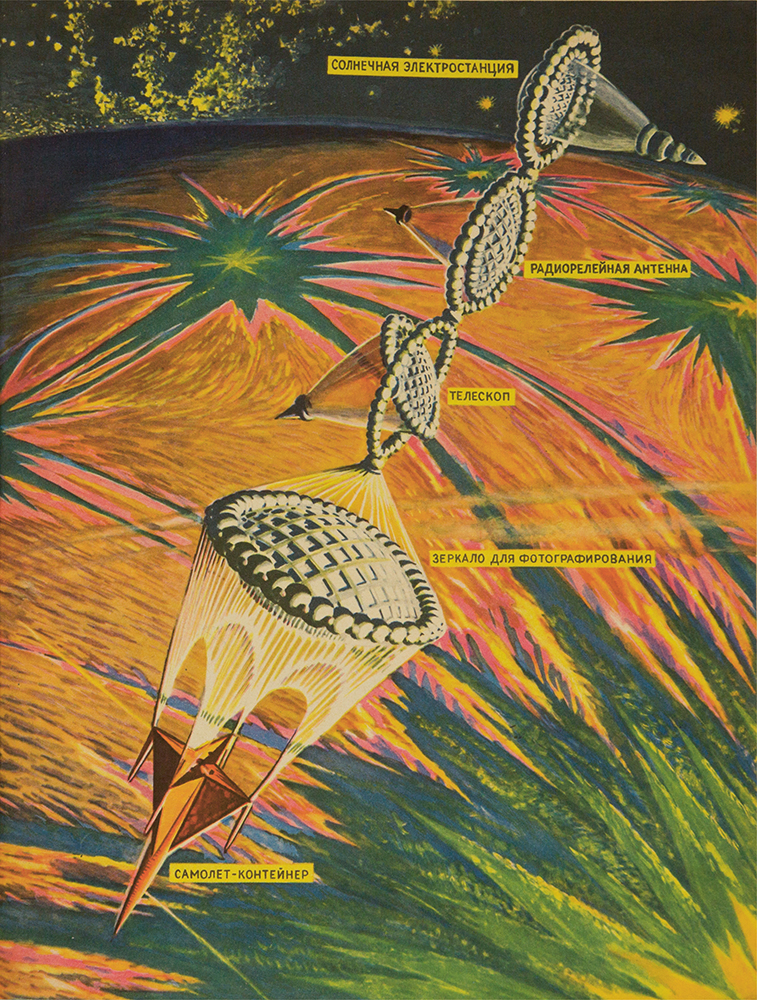

The country’s radical transformation was ideally suited to dreaming big, masterplanning the future and presenting the most incredible and aspirational visions to one’s colleagues and wider society. Printed matter became the most important platform for sharing ideas, the spread of news, protest and propaganda, as well as being a key resource for educating the masses.

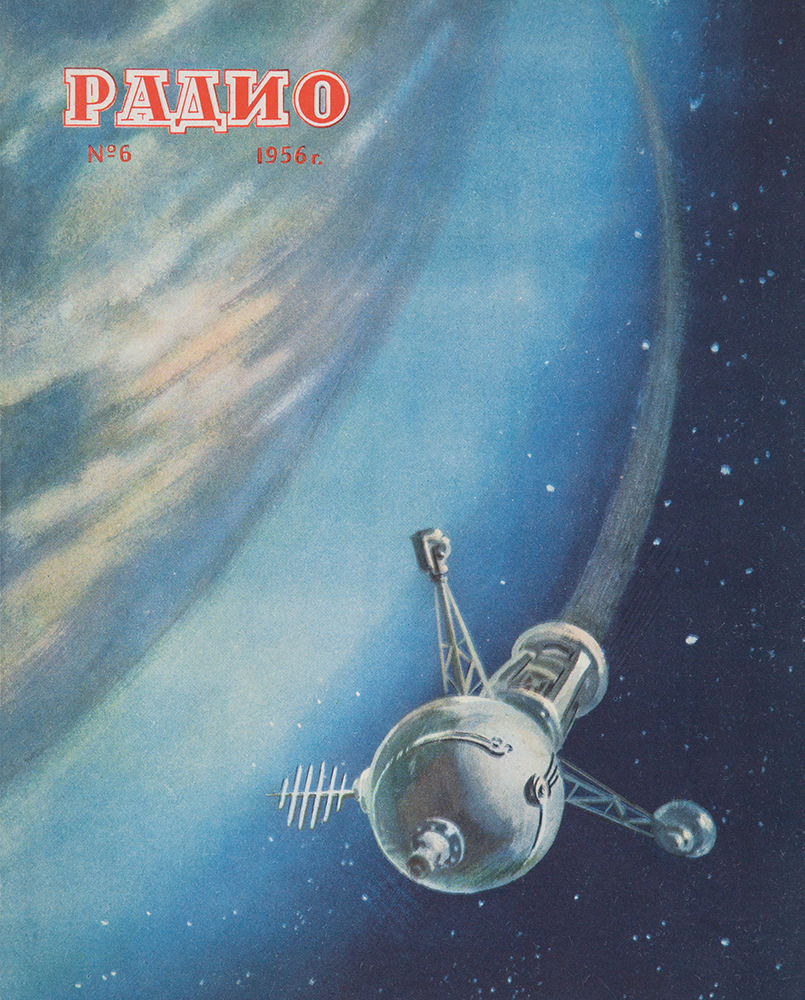

Thus, pre-revolutionary popular-science and literary journals - many with heroic names - such as Vestnik Znaniya (Herald of Knowledge), Znanie – Sila (Knowledge is Power) and Nauka i Zhizn (Science and Life), were brought back into print, alongside entirely new periodicals, with the distinct purpose of popularizing what might once have been considered specialist knowledge.

A significant number of these publications focused their attention on the exploration of Earth, its subterranean and oceanic depths, but more of them focused on the endless mysteries of outer space – each of these frontiers representing the promise of a bright, new Communist future.

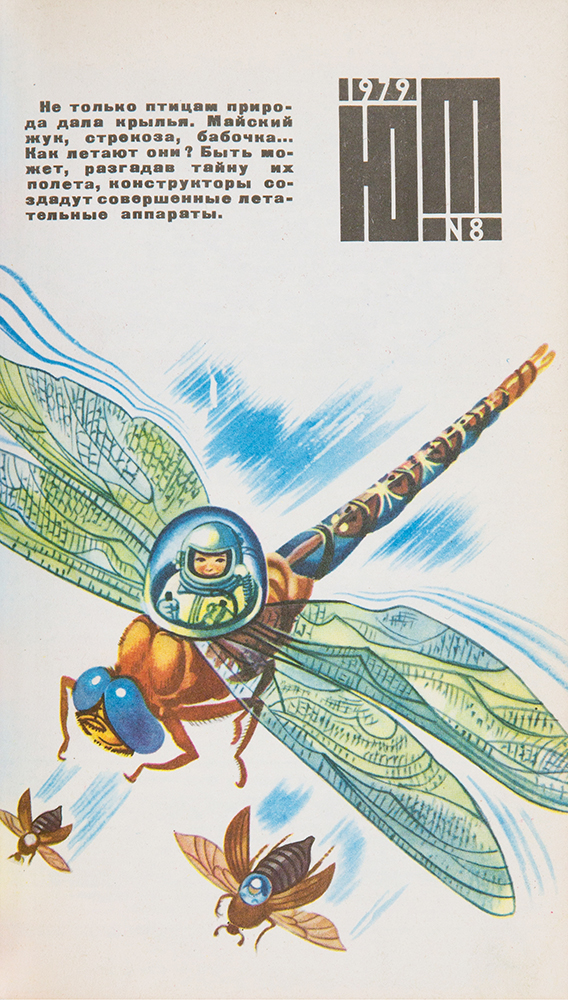

At the same time, the burgeoning science-fiction literary scene that had gradually infiltrated Russia from the West also found its perfect outlet in the magazine Tekhnika – Molodezhi (Technology for the Youth), which to this day, remains one of Russia’s leading popular-science monthlies. It began as a purely technical publication but soon embraced the best of Soviet and international science-fiction writers.

It was through T–M that translations of American authors Isaac Asimov and Edmond Hamilton, Polish author Stanisław Lem and British author Arthur C. Clarke, made their first appearances before the Soviet public.

Though space travel was still in its infancy, it quickly became a prevalent theme of both fiction and nonfiction, and grew to symbolize the USSR’s hopes and ambitions in its race to achieve global technological supremacy.

However, the advancement of Soviet space travel and exploration is inextricably linked to the work of one man - Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), a visionary rocket scientist and mathematician, considered to be one of the founding fathers of astronautics. During his lifetime he published hundreds of scientific writings – both fiction and non-fiction – but he is perhaps best known for his research into the use of multi-stage rockets for spaceflight.

As early as 1903, Tsiolkovsky calculated a velocity required to take a spacecraft into orbit around the Earth using liquid oxygen and hydrogen as fuel. Due to his rather reclusive lifestyle working as a teacher on the outskirts of Kaluga, in western Russia however, many of his early works were written in relative obscurity and went virtually unnoticed when they were first published, among them his article for a St Petersburg scientific journal, ‘The Investigation of Cosmic Space by Reactive Devices’ (1903), which only achieved recognition following its republication nearly ten years later.

Nevertheless, the October Revolution of 1917 signified a major turning point in the dissemination of Tsiolkovsky’s ideas; for a new government looking to inspire a national awakening of pride and superiority, the scientist’s humble background and pro-Soviet ideology provided the perfect narrative. For one Soviet citizen at least, the dreams became reality.

To see more works such as these, and to better understand the artistic side of the Soviet Space Race order a copy of Soviet Space Graphics: Cosmic Visions of the USSR here. This otherworldly collection of Soviet space-race graphics takes readers on a cosmic adventure through Cold War-era Russia. The 250-plus extraordinary images featured, taken from the period's hugely successful popular-science magazines, were a vital tool for the promotion of state ideology. Soviet Space Graphics unlocks the door to the creative inner workings of the USSR.