Fabulous Finn Juhl Furniture: The FJ45 chair

This pioneer of modernism designer created a chair so delicate, it pushed the skills of master craftsmen to their limit

In 1945, Finn Juhl was in his early thirties, and already an award-winning architect. However, that year, the Dane left the architectural practice where he had been working, to start his own design studio, focusing on interiors and furniture.

Juhl had already experienced some success as a furniture designer. Yet, he hadn’t the deep knowledge of carpentry many in Scandinavia possessed. He offset this by meticulously checking and rechecking the physical limits of his designs.

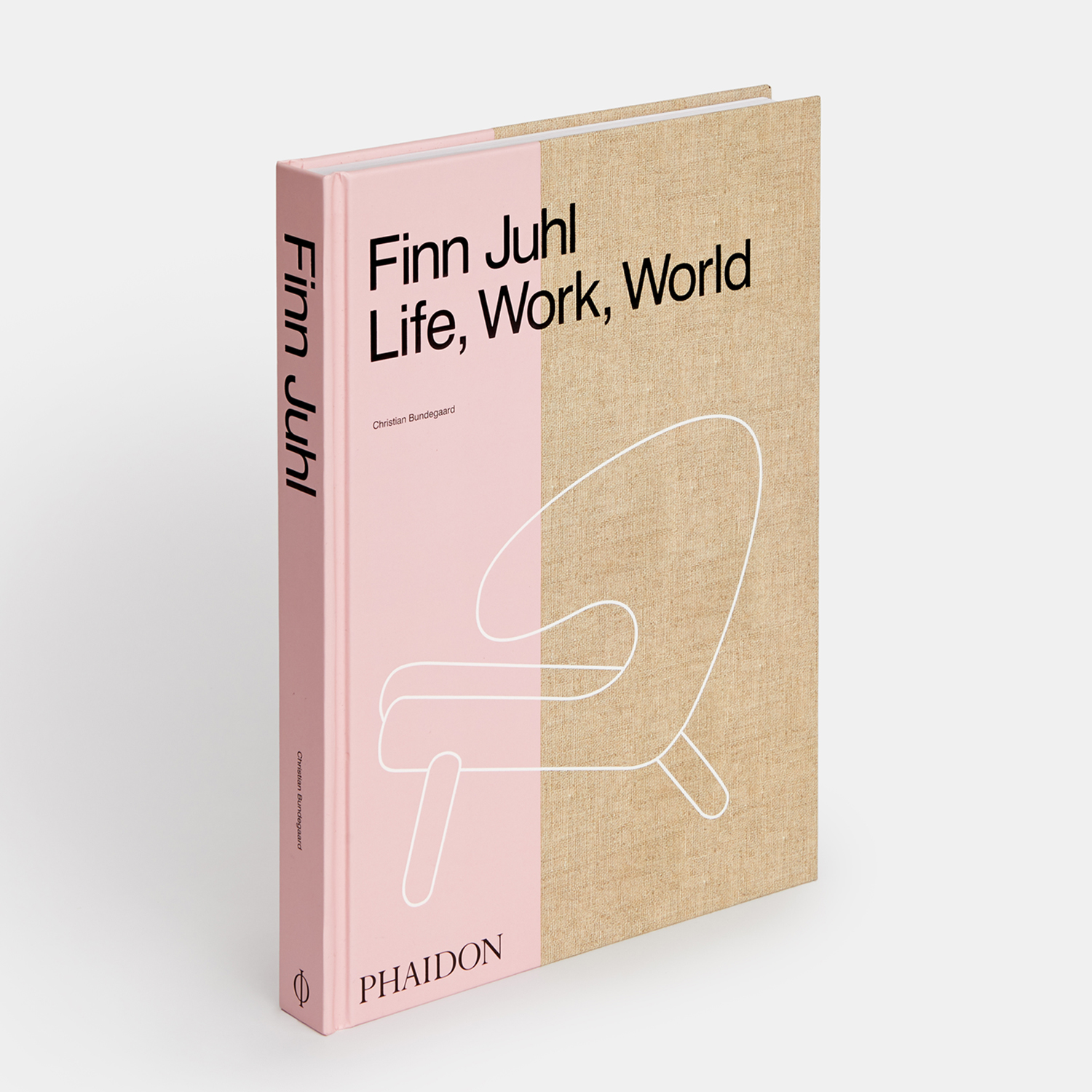

In our new book, Finn Juhl: Life, Work, World, author Christian Bundegaard quotes Juhl as saying that, in 1945, he was “measuring virtually everything I came across to gauge how high armrests ought to be, how high the seat should be and how deep. I had no idea, because I hadn’t learnt to design furniture.”

This tension, between Juhl’s free-form design ambitions, and the stresses and strains that wooden furniture could take is pushed to its limits in one of his finest creations, the FJ45 chair.

“Perhaps FJ45 is Juhl’s best chair,” writes Bundegaard in our new book. “It has an organic suppleness that relates it to the [earlier, 1938 design] Grasshopper Chair, but both technically and aesthetically it is a far more integrated whole.”

Juhl sketched the chair in just four hours, and was clearly influenced by tubular-steel furniture from the Bauhaus school and in work by Charles and Ray Eames, Mies van der Rohe and Alvar Aalto. However, unlike those designers, Juhl chose to work with timber, not steel or ply.

“In opposition to many of the pioneering chairs in tubular steel or laminated wood, Juhl’s chair, though it is incredibly slender, is made of solid wood. It is the static boldness in the slim lengths of wood, the sweeping form and the refined joints that make FJ45 so unique. This is high-quality design and eminent craftsmanship from long before computer- controlled saws and milling machines.”

The structural difficulties were overcome by Juhl’s cabinetmaker, Niels Vodder who brought this near impossible chair to life. “As Danish Design historian Arne Karlsen makes clear, the delicate diagonal bracing beneath the seat had never been attempted, and the ‘stress on the very boldly curved back part of the armrests made demands of wood quality and craftsmanship that no one had ever dared make before’.”

Those risks paid off. The chair won a gold medal at the 1951 Triennale design exhibition in Milan as well as being purchased for the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Yet it wasn’t until 2003 that the work went back into production, after computer-controlled production techniques had caught up, and were able to recreate a chair once so delicate, only a master craftsman could make it.

For more on this chair and many other great Finn Juhl designs, buy Finn Juhl: Life, Work, World here. It's the first-ever comprehensive monograph on one of Denmark's most influential Modernist design pioneers and the man who is generally regarded with introducing Danish Modern to America.