Was Verner Panton the most avant-garde of Danish designers?

The 20th century design visionary took Scandi interiors for a walk on the wild side of industrial production

You only have to glance at the work of the 20th century Danish furniture and interior designer Verner Panton, to realise that practicality wasn’t his biggest concern. He put a multi-coloured swimming pool in the basement offices of Germany’s leading news magazine; stuck his furniture on the ceiling at a 1959 trade fair; and made a lampshade fit for a Bond villain (look out for the shell lamp in the 1969 movie, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service).

This is not the sort of work you’d associate with the sensible world of Danish applied arts. “Panton was ‘Danish’ in the sense that he shared the practical and concrete design approach that characterizes the Danish furniture tradition among his colleagues,” explain writers and academics Ida Engholm and Anders Michelsen in our new book, Verner Panton. “But he appears much less ‘Danish’ if we consider his experiments with new materials and idioms and the role that he assumed on the Danish design scene.”

So, should we view Panton as mid-century design's great avant-gardist? “There are many who consider Verner Panton to be the closest Danish design comes to the ultimate avant-garde,” the authors state.

“He had a desire to create new objects that broke away from the tradition, simply because he wanted to, and because he was able to – not least in relation to Danish applied art – and he was undoubtedly highly motivated to develop a more sincere and genuine contemporary expression.”

However, the authors admit that Panton was not much of a philosopher, and his creative expression was not accompanied by bold manifestos, crowds of acolytes, or crushing social critiques.

“In contrast to other neo-avant-gardists, such as the Situationists who accompanied people like Guy Debord or Andy Warhol, Panton did not build an intense artistic scene around himself but rather held on to approaches related to industrial research and development”, they write. “He was far removed from the kind of eccentricity that characterized Warhol’s Factory and from the cult that other neo-avant-gardists, like the Surrealists, for example, consciously developed.”

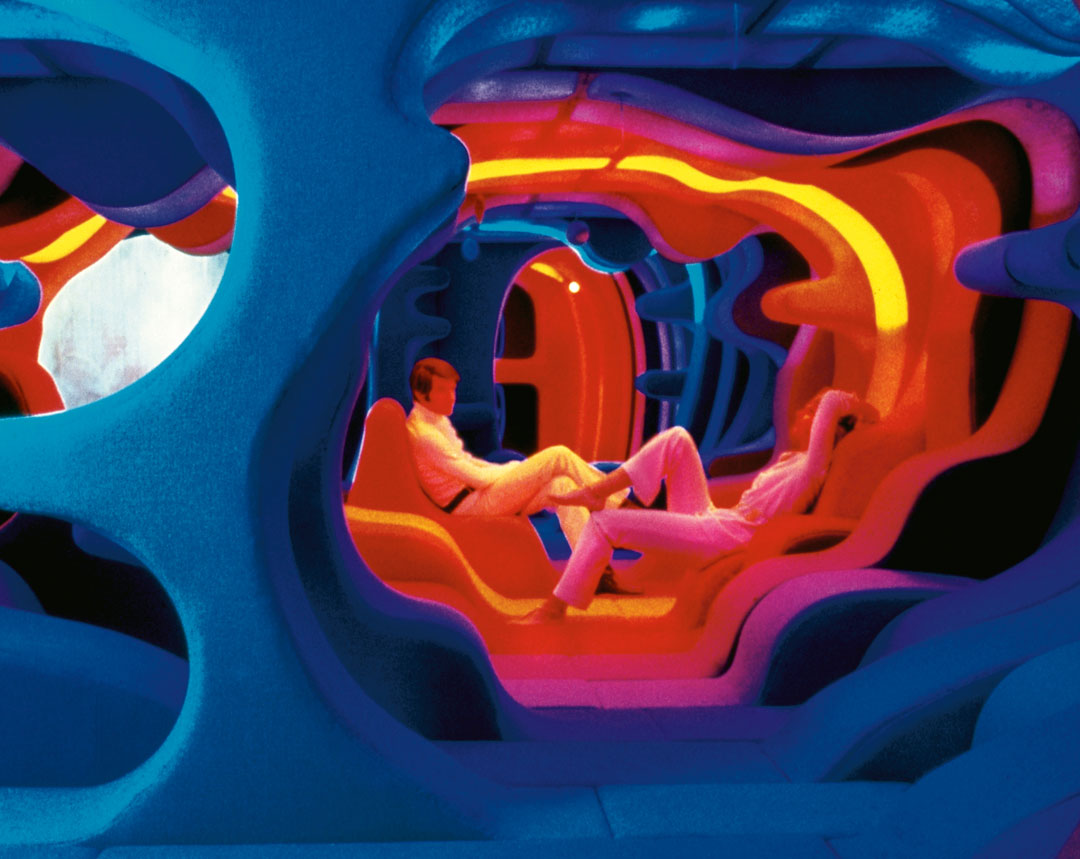

Still, today, we can’t help but look at Panton’s curvy, colourful, immersive environments created in the 1960s ‘ 70s and ‘80s, and see them as stunning departures from what had come before, particularly in the way they prioritized very different qualities.

“In a comparison between Panton and the German design icon Dieter Rams, the German design historian Volker Albus concludes that while Rams championed a strict ‘form follows function’ line,” the authors write, “Panton was interested in feelings and challenges.”

Here, the authors argue, is an interior designer seriously exploring inner space, “where the world is encountered from within: an almost unbounded world of design that can be focused in relation to everyday life and its forms of life.”

These sensual, emotional, heady environments are surely as out-there as many works by his fine-art contemporaries, and might, thanks to the space-age materials used - foam rubber, Dralon and Plexiglas - also be longer lasting.

“Panton’s work exemplifies how wild industrial production can become,” the authors conclude, “because his designs are so concrete, which has helped make them something else than neoavant-gardist intellectualism or just a curious interlude.”

To see more of those creations and to get the story behind them order a copy of our Verner Panton book here.