How George Nelson made us all look a bit closer

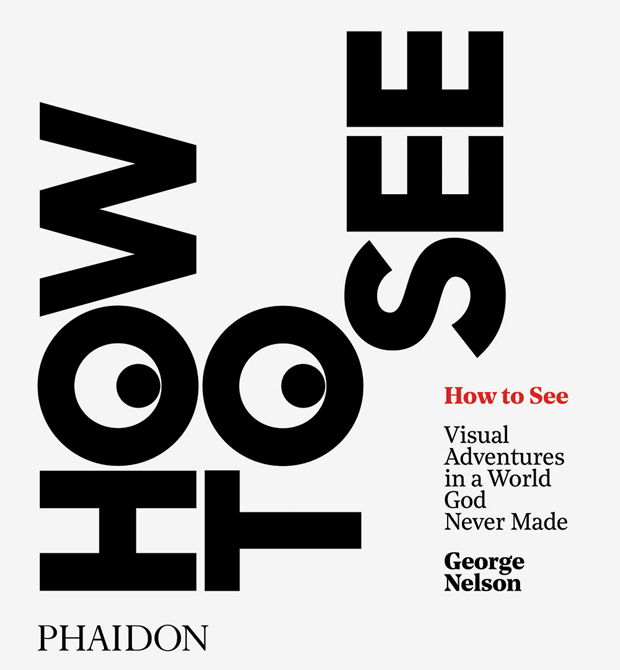

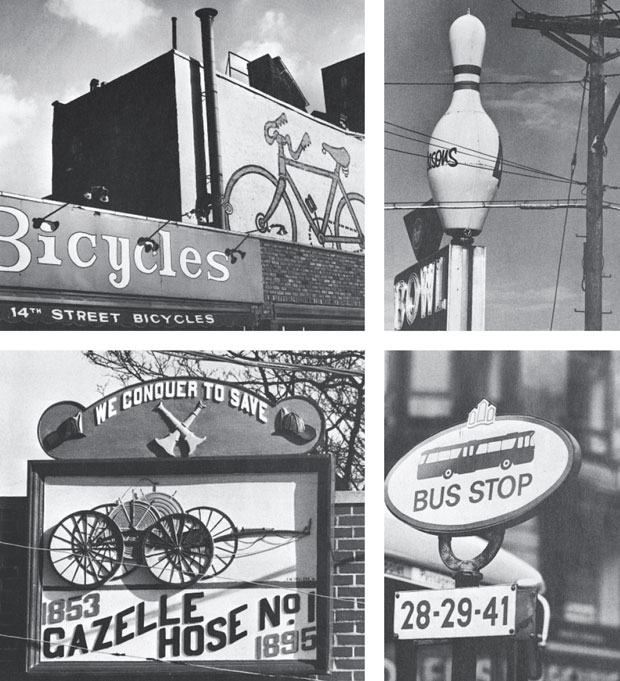

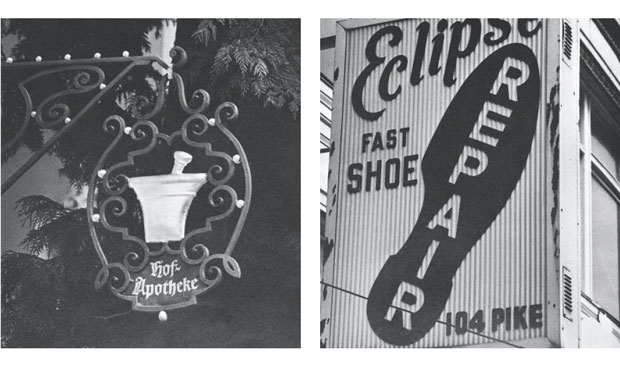

The designer took a camera everywhere he went (in the days before we all did). What he pointed his lens at wasn't particularly remarkable - but what he highlighted in his detail-packed images taught an entire generation how to see

In his introduction to our new George Nelson book, How To See Michael Bierut, Partner at Pentagram Design, wonders what the legendary American product designer would have made of today’s image-driven culture - an age in which the ubiquity of smart phones and social media have made sharing pictures with friends and strangers effortless.

In Nelson’s day, the years in the middle of what would be called The American Century, taking a picture was no simple thing. As his friend Ralph Caplan remembered: “When you looked at a Nelson picture, or at a dozen of them, you did not wonder, ‘How does he get those effects?’ You were more likely to wonder, ‘Where does he find things like that?’ Later you would realize that the scenes George shot were everywhere for the finding: patterns and aberrations in the building environment. George noticed them and, in noticing them, revealed the patterns as extraordinary, the aberrations as understandable, and both as enlightening.”

Of course, taking a picture meant, first, carrying a camera and Nelson apparently never travelled without one of the bulky objects dangling from a strap around his neck.

Beirut takes up the story: "Nelson snapped photos spontaneously and constantly, less concerned about the niceties of artful composition than simply recording the people, places and things that caught his eye, dozens of rolls of film at a time. Upon his return to his office, each roll and its thirty-six images would then be developed and reviewed. These images -most often 35 mm slides - were then sorted, classified, and added to an archive that eventually came to number in the tens of thousands. Augmented by still more pictures of art, architecture and historical events from other sources, they comprised what Caplan called a vast “Ministry of Slides.”

Nelson himself perhaps hinted at this in his own introduction notes to How To See when he wrote: “Awareness, when awakened, has a tendency to spread and expand.”

Nelson’s fascination with images proceeded from his obsession with something he called visual literacy, “an ability to decode nonverbal messages.” He saw this as indispensable to our ability to think critically about the built environment, so often referred to as “man-made” but which he wittily called “a world God never made.” Nelson was quick to acknowledge this skill was often confused with innate and mysterious traits like taste or talent. But he was convinced that we could learn to read images in the same way we learn to read words: through experience, exposure and practice. Find out for yourself whether you think this is true - we do - by taking a closer look at How To See here.