Come with us on a trip to the Noguchi Museum

Stephen Shore & Tina Barney document people and place in a fascinating visual study of Noguchi's own creation

In keeping with the protean nature of his artistic output, Japanese designer and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi was bold enough to found and design a museum for his own work. That he did so in 1985 at the ripe old age of 80 and that 30 years later the museum is inspiring its visitors more than ever is a testament to the enduring nature and aesthetic of his vision.

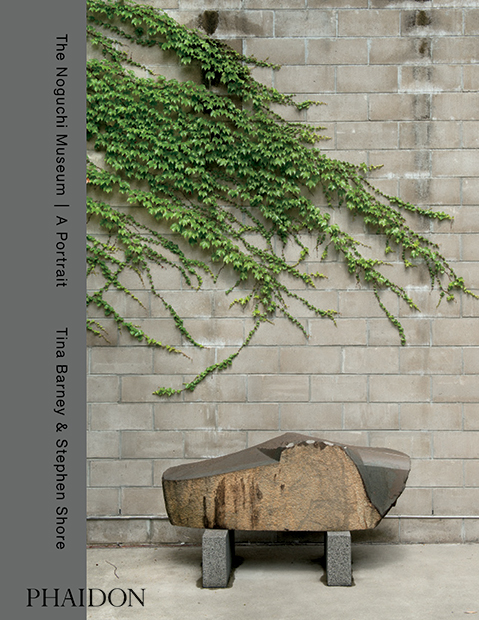

So to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the museum this year, the museum asked Stephen Shore and Tina Barney, two of the most interesting – yet very different – photographers working today, to interpret the place via a newy commissioned body of work which we're publishing in a new book The Noguchi Museum A Portrait.

Shore, of course, is well known to Phaidon readers. One of the most influential photographers living today, his photographs from the 1970s, taken on road trips across America, established him as a pioneer in the use of colour in art photography.

Tina Barney meanwhile, is a much-loved fine art photographer who studied photography in the 1970s at the Sun Valley Center for Arts and Humanities and completed workshops with Duane Michals and Nathan Lyons, among other prominent photographers.

As well as in The Noguchi Museum A Portrait you can see her work in numerous public collections, including: the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Art Institute of Chicago and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Interestingly, neither photographer knew what the other was planning when they started out on the project. The pairing of the formal still lifes of Shore and the intimacy of Barney’s work emerged as a perfect whole only after 18 long months of photographing in the museum. In a way, the two approaches - Barney uses film while Shore has long embraced digital - bring to mind Noguchi’s incorporation of both tradition and modernity in his own work and in the design of his museum.

Shore documents the physical museum space, including the artworks and their articulation through that space. Barney meanwhile, hones in on the juxtaposition of those works and the visitors who make the pilgrimage out to Queens. There are links between artworks and artwork viewers though they are rarely overt, and often subliminal:for instance the monochromatic tones of a lady’s blouse and skirt ensemble complementing and contextualizing the grey texture of a wall tile or brick in the background.

“After spending 18 months there you can kind of generalize,” Tina Barney told Phaidon.com last week. “The visitors to this particular museum were very approachable and very easy to work with. I don’t know if one can say that that's the kind of person who goes to the Noguchi museum but I might say that's whta I found. Maybe they are more peaceful, maybe they are more zen." Certainly the museum had an effect on Barney. "There’s an intimacy and an affection to it that made me think, wow, he did a great job. I’m the least zen person, but I grieve that I never met him.

Our readers will probably know Noguchi first and foremost via his exquisite, sculptural table for Herman Miller. It's a perfect example of how the Japanese American designer managed to bring a sense of poetry and calm to everything he created over six decades of a prolific and international career.

As a designer Noguchi became one of the Modernist era’s most prominent and sought after talents, celebrated for products and furniture that took ancient Japanese ideas and traditions and translated them into beautiful products that could enhance the quality of everyday life in the Western world.

Jenny Dixon, the museum director says that the museum was an outgrowth of the way in which he worked as much as it was an embodiment of his art. Ever the iconoclast, Noguchi moved his residence and studio from Manhattan to what was the no-man’s-land at the border of northern Long Island and southern Astoria, Queens, in the early 1960s. Noguchi purchased a commercial building at a time when most artists were settling in lower Manhattan.

In the following years he expanded what would these days be called a property portfolio by buying a gas station and factory across the street. By 1985 this would form the basis of the museum. The designer sincerely hoped that people would find it "a place to reflect and to see an alternative existence to the one they have now.”

You can get a palpable sense of that existence in Barney and Shore's photographs, Jenny Dixon's beautifully written foreward as well as some fascinating archival photography at the back of the book. Its clever design and fabulous tactility give you a sense of the experience of a visit to this most wondrous of museums. Take a closer look and pre order it here.