The playfully productive world of Mario Bellini

New book captures the childlike imagination of a designer responsible for inspiring the ubiquitous people carrier

Is Mario Bellini the anti-Dieter Rams? That might seem like an odd notion, as the two important European designers, born around the same time, went on to shape our manufactured environment in similar ways. Both began their careers during the post-war boom, when early micro-electronics and new synthetic polymers changed both the kinds of goods companies commissioned from designers, and the means by which those goods could be made.

However, while Rams, the long-standing Chief Design Officer at Braun, reduced his working beliefs down to his famous ten principles for good design – the most famous of which was ‘Good design is as little design as possible’ – Bellini insisted on absolutely no rules when he came to work on an idea. Perhaps that's why The New York Times recently described him as "One of the last great protagonists of Italian design."

As Bellini explains in our interview with Enrico Morteo the author of our new book Mario Bellini Furniture, Machines & Objects “I’ve always rejected the idea that there’s a method for doing what is called ‘design’.”

“I think of a design project as an exploration that involves both the mind and the senses,” he goes on. “In order to understand something fully I must test it and investigate it thoroughly, just as children do, when they touch and taste everything around them.”

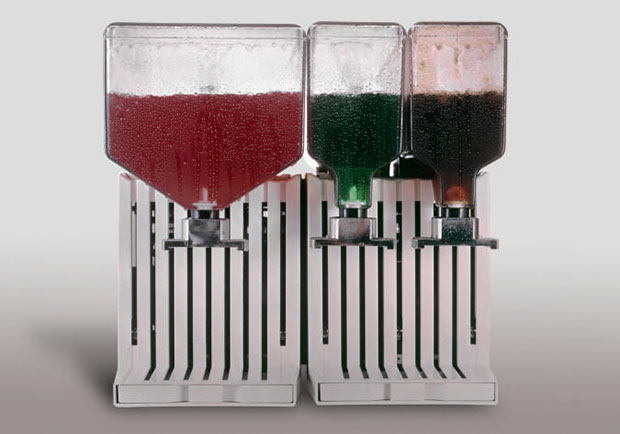

By retaining this childlike point of view, Bellini has produced a hugely impressive body of work during his adult working life. It includes computers, calculators and typewriters for Olivetti; automobile work for Fiat; cameras for Fuji; headphones and electronic instruments for Yamaha; televisions for Brionvega; jewellery for Cleto Munari and Faraone; washing machines for Triplex; and furniture for Vitra, Cassina and B&B Italia.

All these were made in addition to Bellini’s other career interests, which has seen him work as an architect since the early 1960s, as chief editor at Domus magazine 1986-91, and as a lecturer and teacher at a number of different institutions at various points during his career. Little wonder then, that the New York Times described Bellini as “one of the last great protagonists of Italian design.”

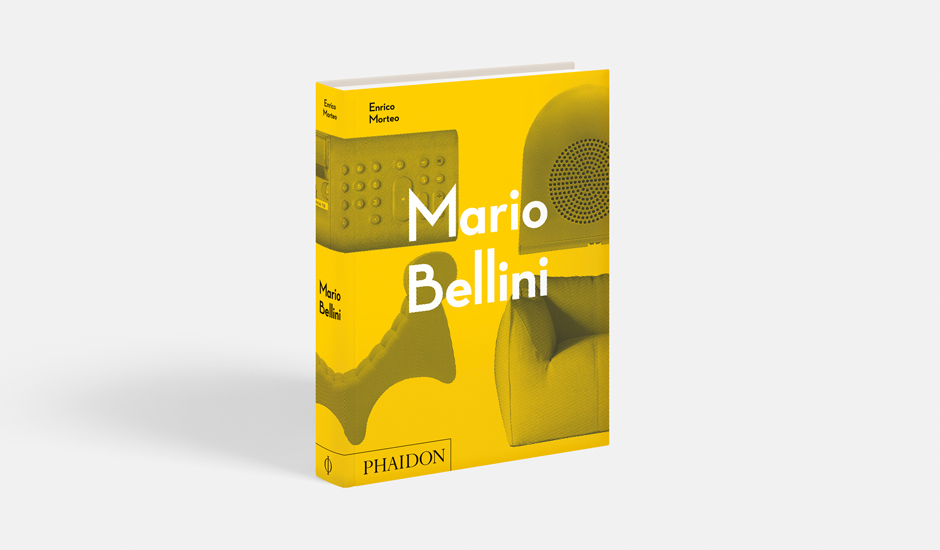

Our new book, which is subtitled Furniture, Machines & Objects, focuses on Bellini’s product design, and stands proudly alongside our other innovative and acclaimed monographs on the likes of Ettore Sottsass, Achille Castiglioni and Dieter Rams.

This handsome book, with a tactile soft-touch laminated cover (think luxuriously spongey in feel), is the first to completely and exhaustively catalogue Bellini's design work, presenting items thematically, from small run banking calculators to mass market sofas and lighting.

Though it concentrates on Bellini’s design output, it also captures the playful, expansive manner in which he came up with the ideas for those designs really bringing the designer's oeuvre to light, illuminating and explaining his methodology. This is one book you'll walk away from truly enriched and nourished (if you can bring yourself to put it down, that is).

His unusual concept car, the MoMA Kar-A-Sutra is a case in point. Bellini made the vehicle for the 1972 MoMA exhibition, Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. But rather than think of an automobile as a vehicle, he reimagined it as a domestic space on wheels. The fun, irreverent design that never went into production seems visually at odds in its boxiness with today's super sleek, aerodynamic designs; yet a key aspect of the car’s influence can be seen quite plainly on today’s roads.

“If, as automobile historians now unanimously maintain, my approach to imagining the Kar-A-Sutra marked the actual beginning of the trend for people carriers,” Bellini explains in our book, “it would mean that in some way that design has influenced nearly fifty per cent of all the cars built across the world since then.” Was Mario Bellini responsible for the birth of the people carrier?

For a smaller, though no less durable innovation, take a look at the HP-1 headphones, created for Yamaha in 1975. Bellini disliked the sensation of the metal band resting on his skull, and so came up with an arch and strap arrangement, with a strip of leather resting on the top of the head. Though a last-minute change, this innovation was soon adopted by other manufacturers around the globe.

Then there’s his best-known chair, the CAB 420 for Cassina, which began as a stick drawing – “the simplest and most basic chair possible,” as Bellini puts it, “a chair like the ones children draw.”

Over this frame he fitted a thick, zip-on leather cover – a skin or boot for the seat, as he puts it. It was an unusual design solution, which combined artisanal leatherwork with mass-produced steel frameworks; yet the CAB 420 has settled well into contemporary interiors across the globe.

Some time after Bellini came up with this design, he noticed that the leg of an ancient Egyptian chair in a Cairo museum looked remarkably like his CAB design, leading the designer to conclude that his was “a new invention, and yet a design as old as the world.”

“After all,” Bellini goes on, “we are all part of the river of history, and our designs are no more than the latest link in a chain that goes back through the mists of time.” A typically open-minded conclusion from a designer for whom, despite Rams’ dictums, more is definitely more.

You can order Mario Bellini Furniture, Machines & Objects here.