The Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design gets a great review in the influential Creative Review

"The Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design reminds you that when print works well it can work like nothing else"

We're not in the habit of blowing our own trumpets at Phaidon. However, when a magazine we respect and adore in equal measure reviews one of our books in such a thought-provoking, insightful, intelligent - and yes, positive - way we coudn't help but bring it to your attention. So thank you Mark Sinclair and thank you Creative Review for taking the time to assess The Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design in such a detailed and careful manner. With courtesy we repost The Creative Review review below.

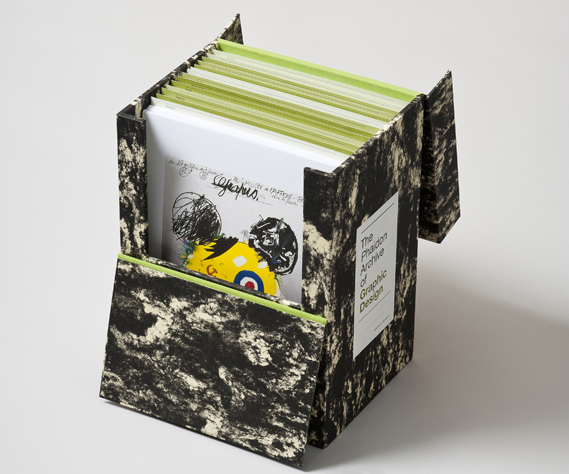

The Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design is a boxed edition of 500 A4 cards detailing some of the world's most important examples of the medium. At 13kg it's an object with some presence, but how will it weigh up with readers? While its considerable size and loose leaf format initially makes you wonder 'isn't this what the iPad is really good at?', handling each of the individual cards – the cover of Eric Gill's Typography (1931), or of an issue of David Carson's Beach Culture (1990), for example – reminds you that when print works well, it can work like nothing else.

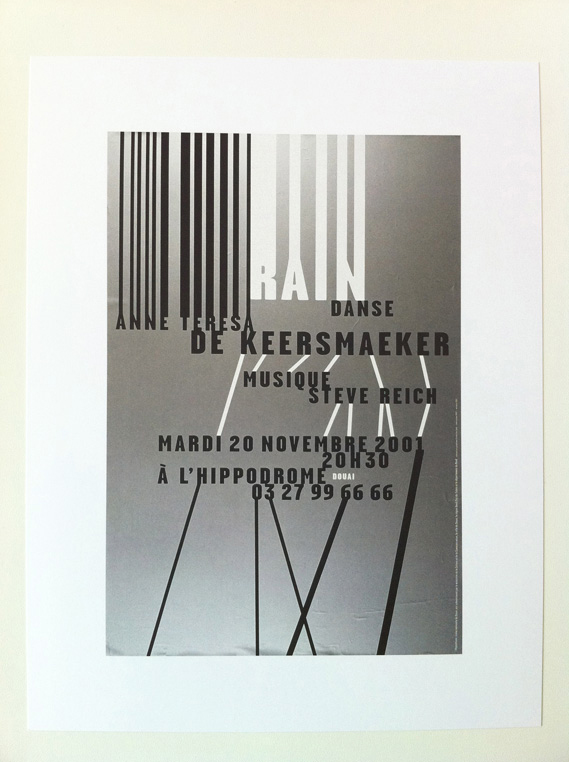

In a sense the packaging (the large box comes harnessed in a sturdy carrying handle) is a bit of a distraction: the content is the main event here. It's a pleasure just to sit and look through the range of magazines and newspapers, posters and advertisements, typefaces, logos, symbols, books, album covers and motion graphics, which have been selected by a panel of designers, writers, critics and historians. (In the name of full disclosure both myself and CR's Eliza contributed research to the project but weren't involved in the selection process.)

This is Phaidon's stab at a graphic design canon and judging by the editorial process outlined in the foreword – thousands of entries were whittled down to 500 – it's been a considerable undertaking. The Archive's introductory text also explains the reasoning behind displaying the work across 500 large-format double-sided cards, instead of making a 1,000-plus page book, or an app. Primarily, Phaidon claim, this enables the reader to easily organise the work however they like; to siphon off just the posters, symbols, or book covers, or even to display the images as prints.

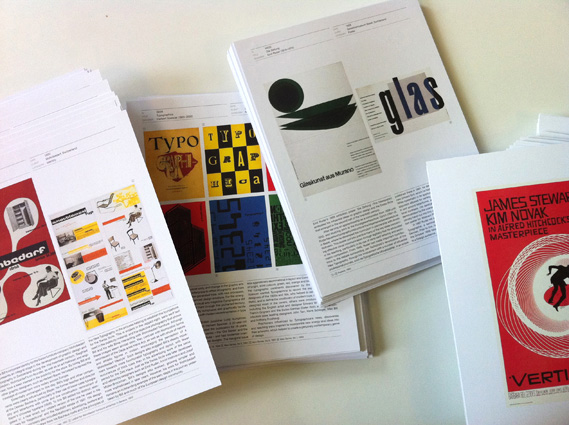

And despite the pull of the digital potential for something like this, it doesn't feel like the publisher's explanation is post-rationalising the design approach. It strikes me that being able to simply pull out individual entries will appeal (and be of practical use) to creative professionals, and something the general reader will equally enjoy. Each card boasts a single, well produced image of the particular work on the front, the reverse features a selection of additional related images and a few hundred words of text.

The 500 picture cards also put more emphasis on the reader to act – to compare and contrast, to make connections between works that are perhaps centuries apart. Readers can arrange the cards to any theme they desire, too, and dividers are supplied with the set in order to categorise by format – 'Book Cover', 'Identity', 'Film Graphics' and so on.

The cards are initially arranged in chronological order, with work dating from 1377 to 2012, and it's a treat to dip into the various styles, schools, tastes and production methods bookended on one side by the Gutenberg Bible and the Nuremberg Chronicles, and dot dot dot magazine and Leftloft's Documenta art festival designs on the other. Phaidon plan to issue further batches of cards in the future, so that the Archive can be updated both with historical additions and recent projects.

One point to note, however, is how well the cards will stand up to repeated viewings. Entries of course have to be put back in the correct place in order to be found again later (not a tricky concept, but one likely to go awry when the cards are routinely referenced) and this could make for a less than enjoyable user experience. The emphasis is firmly on interacting with the work, but the down side to this is that once cards are removed from their slot in the system, the system starts to fall apart. And that's something that conventional books, with their fixed pages and indexes housed reliably at the back, don't really have to worry about.

Another issue is the standing Phaidon places on its own printed products within the the centuries of graphic design collected here. As a "client", Phaidon actually has the largest number of projects represented in the Archive – five are listed in the index. Of course, with names like Alan Fletcher and Irma Boom directly associated with the creation of some of the company's most famous books (Fletcher designed both The Art Book and his own The Art of Looking Sideways; Boom the Hella Jongerius monograph) some crossover is perhaps to be expected. But out of 500 pieces, to devote five entries to one's own publications – the Bauhaus is cited twice; Monotype, three times – seems a little surprising.

That said, the sweep of the selection is exciting and impressive and it does feel like the biggest decision – to print each of the entries as a single page, instead of binding them in book form or formatting them for screen – went the right way. The temptation to digitise all the content must have been considerable (and will no doubt happen soon), but it's impressive to see print fighting back like this.

At £140 the Archive is perhaps not quite as accessible as it thinks it is, but it goes some way to suggesting what the most significant and visually arresting moments in the history of graphic design might be. Mark Sinclair, Creative Review