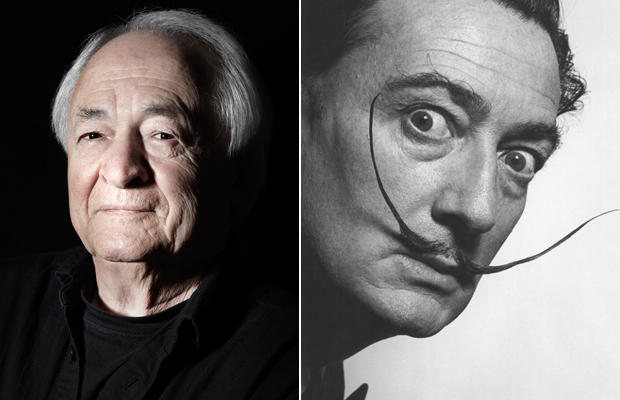

Pierre Dinand's incredible Salvador Dali stories

The legendary perfume bottle designer talks to Phaidon about his secret collaboration with the surrealist painter

Pierre Dinand's collectible perfume bottles, which for over 50 years he has designed for practically every fashion house you can name, have become objects d’art in millions of homes the world over. In his lifetime, the designer has made bottles for everyone from Pierre Cardin to Madame Rochas and Yves Saint Laurent, for whom he created the genuinely iconic Opium. Dinand worked with all of these designers on a personal level, and claims, humbly, that it was simply his ability to listen that allowed him to house their abstract ideas in shapes that would come to be celebrated all over the world. This sense of designing a “home” to both the idea and the scent is absolutely central to his practice. A trained architect-turned-bottle designer, he only happened upon the trade that would come to define his future by chance when Madame Rochas asked a young designer at an advertising agency to create her a perfume bottle: “Once I had made one, it never stopped,” says Dinand, who kept offices and workshops in Paris, London, New York and Tokyo throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Yves Saint Laurent, Opium, bottle designed by Pierre Dinand in 1977, photographed by Damien Fry (2011)

There was however, one collaboration the legendary designer worked on that never came to fruition, despite three years of work – this was with Salvador Dalí. In an exclusive interview with Phaidon Dinand has revealed that the pair worked together on a scent commissioned by the fragrance company Shulton, responsible for Old Spice. “We would have dinner with the president, his wife, and, of course, Dali’s wife Gala, who was already 78/79 years old by that time," Dinand tells Phaidon. "I remember she was often playing with my feet under the table, saying, ‘Come to my room young man.' It was funny. Dali didn’t care; to the contrary, he was trying to find young men who would make love to his wife!

We spent probably three years on the project in this crazy way, but we never did the fragrance. Dali had absolutely no idea of what could realistically be done in glass. He thought you could do anything in glass, but no, glass is a very different material to use and you cannot be too long, too pointed etcetera – it’s not like plastic or like metal. Often, what he wanted to do was absolutely impossible to realise, but it was more like fun for us anyway, the fragrance was like a dream. I must have met Dali to talk about the scent 20 times, mostly in New York, and we even went to his house in Catalonia at one point to discuss what kind of thing we could do, but always his ideas – so crazy.

After his death the secretary signed a contract, and the famous bottle with the nose and lips was created, but that was not really what Dali would have wanted. I had a huge file of drawings from Dali on the Shulton project. I don’t know what happened to them, though. I never asked any money for my work on it because it was so much fun to meet him and to work with him. and to just exchange ideas with him. I had a lot of admiration for his work, but also because he was such an incredible character."

Sculpture of Pierre Dinand's most iconic bottles, photographed by Damien Fry (2011)

“I remember one time we went to a big French restaurant in New York with Dali and somebody from the fashion industry – Diana Vreeland – an incredible woman. The man from Shulton asked Dali to choose the wine, and he chose the most expensive, of course, and then he asked to taste it, so they gave him a glass. Dali leans his head back to drink and stays transfixed, looking upwards for at least one minute. We are all looking at him and, finally, he says: ‘the wine is excellent, but the ceiling? The colour of the ceiling is very bad, you have to change the colour…” He asks for scissors, takes a part of his tie and cuts it off saying, ‘This shade of red will be excellent.’ The man from the restaurant changed the colour of the ceiling by the following day! There were always many unexpected things like that."

Calvin Klein, Eternity, designed by Pierre Dinand in 1988, photographed by Damien Fry (2011)

“The thing I most remember about working with him is still the flies. He would sit with his cane in a red throne he had had made, and from six o’clock to eight o’clock he would receive his American clients, and he would always have his box of flies to hand. He would show the print and then ask them how many flies they wanted – a billionaire from Texas would say ‘I want one please,’ and the other guy, ‘I want two!’ For each fly Dali squashed he would charge $1,000 dollars, so a $1,000 print could easily be three or four thousand dollars, incredible - and all in cash, no cards or cheque. He didn’t handle the money though; he never carried money. I remember once he ordered these expensive cigars and I paid 350 dollars for them upfront. He would say, ‘Oh, I am sorry Pierre, I don’t have any money with me.’ His relationship to money was so funny, especially because the anagram of his name is Avida Dollars." Interview by John-Paul Pryor for Phaidon.com

Dolce and Gabbana, Light Blue, designed by Pierre Dinand in 2001, Photographed by Damien Fry (2011)

If you're interested in learning more about influential product designers of our times, make sure to check out the Phaidon monographs on Dieter Rams, Hella Jongerius, and Naoto Fukasawa. For more insight into the work of surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, Dalí by Phaidon is a comprehensive introduction, while the later book of the same name is a re-evaluation of some of his most seminal works.