The Tulip Garden author Polly Nicholson on the colours, the culture, and the rare bulb that costs more than a house

Nicholson started cultivating tulips15 years ago, and now has the largest collection of historic tulips in the UK. We asked her about her fascinating journey

The tulip is one of the world’s most loved blooms across the world. It’s the most-sold flower in the United States and is poised to knock the rose off the top spot globally. There are over 2,500 different varieties currently registered and almost 2 billion bulbs produced annually in Holland alone. High time then, that Phaidon published a book on the tulip we thought.

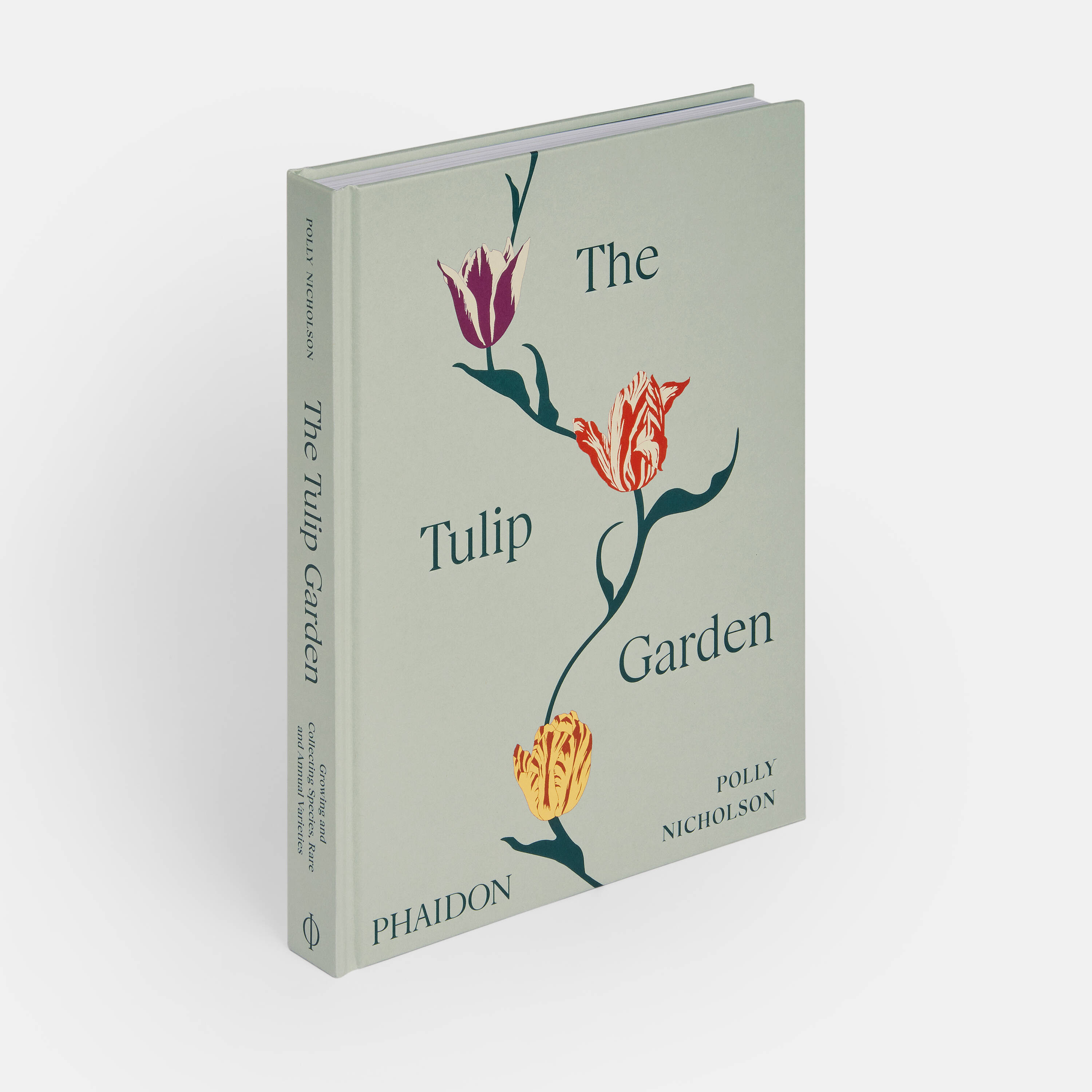

Our book The Tulip Garden: Growing and Collecting Species, Rare and Annual Varieties showcases a unique collection of the rare and covetable tulips at Blacklands, the beautiful English country garden of expert tulip grower and author Polly Nicholson. Combining the flower’s rich cultural history with expert tips and growing advice, Nicholson provides a comprehensive introduction to cultivating species, historic Dutch and English Florists’ tulips, along with the popular annual tulips we see in gardens and parks across the world.

Species Tulips. T. ‘Peppermintstick’ in a tulipiere by Katrin Moye. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Species Tulips. T. ‘Peppermintstick’ in a tulipiere by Katrin Moye. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Bringing to life varieties that date back to the 16th century, Nicholson demonstrates how these treasured bulbs and more modern varieties can be grown today – whether in herbaceous borders, naturalized in grass, in containers, or in cutting beds. She shares details of her favourite varieties and combinations, as well as information on how to plant and care for them based on her own experiences. Meanwhile, the stunning setting and atmosphere of Blacklands is beautifully captured in newly commissioned photographs by Andrew Montgomery.

Nicholson started cultivating tulips more than 15 years ago, and now has the largest private collection of historic tulips in the UK. She has appeared on BBC Gardener’s World, Radio 4, and been featured in Gardens Illustrated, Country Life, The New York Times Style Magazine, The World of Interiors, and House & Garden.

She’s also the owner of Bayntun Flowers – a small organic flower farm in Wiltshire, southwest England – and every spring at Blacklands, she runs workshops and flower events, opening her garden to flower-loving visitors from across the world.

We caught up with Polly and asked her about the long and fascinating history of tulips, why the plants are scientifically more complex than humans, and how tulip mania led to a bulb that cost the same as a house.

A selection of Dutch Historic breeder and broken tulips in vintage French, salt-glazed jugs, sitting in the cool of the coach house. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

A selection of Dutch Historic breeder and broken tulips in vintage French, salt-glazed jugs, sitting in the cool of the coach house. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

What sparked your initial interest and how did the love grow? My love for flowers certainly didn’t come from my parents. My mother had wonderful taste but the idea of arranging a bunch of flowers was a complete anathema at to her. We had this beautiful large country garden but virtually no flowers in it at all. I inherited my love for flowers from my maternal grandmother who was a strong woman, but who had a soft side to her, which was gathering wildflowers.

When I was tiny we would go and stay with her in Dorset and pick wildflowers and put them in little vases. And that’s where the love came from initially. All through my life, all through university, my friends thought I was completely mad because I’d go for walks and come back with armfuls of flowers that I’d put in the kettle, because there was no vase.

Favourite Combinations for Container Plantings. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. ‘Antarctica Flame’, ‘Disaronno’, ‘Havran’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Favourite Combinations for Container Plantings. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. ‘Antarctica Flame’, ‘Disaronno’, ‘Havran’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

When did tulips enter the picture? Tulips came about when we first moved to Blacklands. I was relatively young, in my mid-thirties, with an enormous garden and I didn’t know where to start. Filling the beds up with a mass of tulip bulbs was a quick fix and gave me a bit of confidence that I could design something, even if it wasn’t a fully planned herbaceous border at that stage. I always had an incredibly strong sense of design and of what I do and don’t like. So I found that whole process of decision-making really easy, and a good way of gaining some type of control in the world I had down here.

When did the history of tulips become significant for you? It’s a really good question because when most people think of tulips they’re thinking of colour, but the history of the tulip is such a long and interesting one. My interest was piqued first of all when I was working at Sotheby’s. I did English literature with medieval art and architecture at university and had this amazing first job which was as a junior cataloguer at Sotheby’s. I was there for a few years until we moved abroad for a while. But I started doing the cookery and gardening books. And I think it was through cataloguing these early gardening books that I learned about the whole world of herbariums and florilegium.

Art has always had a huge allure for me. Wherever I’ve gone I’ve sought out paintings or textiles or ceramics with tulips in them. I’m like a magpie, I spot them wherever I go. Now I spot the tulips I grow in old master paintings which is really nice.

English Florists’ Tulips. Breeder and Broken Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. ‘Agbrigg’ Bybloemen (broken). Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

English Florists’ Tulips. Breeder and Broken Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. ‘Agbrigg’ Bybloemen (broken). Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

What makes the tulips you grow different? For a start you can put your nose to them and know that you’re not inhaling a lung full of chemicals. Many of the tulips which I grow do actually have a delicious, honeyed scent to them which you would never get in a commercial tulip. Commercial tulips are dressed in plastic, so they smell of plastic. My tulips smell of the great outdoors and soil above all else, because that’s what they’re grown in.

Why this book? I wanted to help the greater gardening public understand that you could do this in an organic and sustainable way. The tulip industry has become so commercialised in terms of numbers and chemicals used, and in terms of growing and the distances that the flowers are freighted. I think we’ve become removed from the way of doing it in the old fashioned way, which is good for not just us, but for our environment. And as I’ve become more confident and experienced, I’ve been investing in much more interesting bulbs, and then keeping them growing, year on year. So it’s become this whole act of continuing life as opposed to the very short annual life cycle of the bulbs which most people will buy for their garden.

It seems such a lot of work for such a short amount of flowering time! You say that but a lot of the older varieties which I specialise in will flower for up to nearly three weeks in the ground. The tulips are being grown to their full potential and I’m not cutting them half-ripe and then freighting them around; I’m growing them when they’re a massive great big flower, full of life and goodness, they last that much longer in the vase because of that.

The historic collection I grow is a huge amount of work, but in terms of how I grow the annuals, or species tulips in the garden, it’s an awful lot less work, because I’m never planting them in herbaceous borders as has been the norm throughout the twentieth-century. Also, I’m not digging them up. I never plant them in the ground for a quick burst of flower, dig them up, throw them away, and start again. That’s not my way of doing it. So actually it’s a lot less work in the long run.

English Florists’ Tulips. Breeder and Broken Tulips. T. ‘James Wild’ in all three ‘stages’: breeder, flame and feather. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

English Florists’ Tulips. Breeder and Broken Tulips. T. ‘James Wild’ in all three ‘stages’: breeder, flame and feather. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Give us a tulip fact that surprised you during your research I’ve got my best new fact for you. I’m helping the RHS with a project, which began when I was talking to them about how they press their tulips. They’re sending one of their flower collector gatherers to spend a day with me and to take samples from my historic tulips for their archive, their herbarium. One of their botanists told me that a tree has one gigabase (a measurement unit to designate the length of DNA molecules) in each genome. Humans have three gigabases in each genome, but tulips have 34 gigabases in each genome. That illustrates the complexity of tulips. They are 34 times more complex than a human being!

How are tulips celebrated in different cultures around the world? Turkey still has a festival in Istanbul every spring. Ottoman Turkey was where all of the first breeding of tulips happened in the 1500s and then again in the 1700s - those were the really rich periods. In Ottoman Turkey they were harvested from the stans: Kurdistan, Uzbekistan, Tadzhikistan, and taken to Istanbul and Persia and then bred into these, initially very stylised, needle-tipped tulips, which I have in my species collection under the name Tulipa ‘Cornuta’ (previously called acuminata).

And those are almost identical in appearance to all of the stylised ones you’ll see in the Iznik tile work from that period. So they started off being like that which was sort of an exaggerated form. Then, when they came over to Europe in the later 1500s, they developed into myriad different types of tulips which now we have classified into 16 different divisions to try and create some sense out of the thousands of different cultivars which we have today.

Growing Dutch Historic Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Growing Dutch Historic Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Holland has the most obvious profile; the tulip has become a national symbol of the country. I believe that there’s quite a big following for tulips in Japan and Korea too, and also the west coast of America, which is a massive tulip growing area. America full stop actually.

In the beginning of the twentieth-century, the Dutch were shipping millions of tulips over to America. They were in vogue in the tens and twenties and grown in these exquisite colours, which have been known as ‘art shades’ - moody, bruised colours which are represented in our collection in the Dutch historic breeder chapters.

Are tulips threatened by climate change? Last year was definitely the worst year that growers in the UK and Holland have had. We used to have a saying that you need cold for the roots, rain for the shoots and sun for the fruits. It’s not like that anymore. We’re not getting proper long cold periods which kick start a process called vernalisation whereby the flower is created. The bud is kickstarted into action for the following season. If winters carry on like this I wonder how long we’re going to be able to guarantee these displays of tulips we’ve taken for granted. And secondly come the spring we’re having long periods of wet which then perpetuate this build-up of mould, botrytis tulipae, known as tulip fire.

That has been a massive issue in the UK recently, particularly last year. It starts off as brown spots and the flower becomes distorted and brown and eventually it’s so mouldy that if it rains or you disturb the flower it will release spores that look like a smoke – hence the tulip fire. It can reside in the bulbs so your precious stock of very rare historic tulips can be very seriously affected. So my growing has become even more concentrated on the husbandry and constant inspections and care, and I make sure that it’s first rate at all times.

Dutch Historic Tulips. Breeder Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery (page 114, bottom right) T. ‘Madras’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Dutch Historic Tulips. Breeder Tulips. Photography by Andrew Montgomery (page 114, bottom right) T. ‘Madras’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

The tulip arrangements in the book are simple but beautiful. Do you have a display approach you could share with readers? I think it has to be instinctive. I would never employ a trained florist because I find that with all the arrangements I make, because I’m choosing all of the flowers which I’m already growing, and because the foliage is all part of my garden, they tend to work together whatever I do.

I’m completely untrained. What display I come up with depends on my mood. It’s very untutored and very natural. Because I grow so much I’m generous with the quantities I use in arrangements. I’m having to learn from people like my favourite florist Shane Connelly who has a less is more approach. That’s rubbed off a little on me. But I like generosity. I think flowers represent generosity. The way the earth is offering them, and the joy they give you picking them and through the act of giving them to other people as well.

What are the traditions or rituals associated with tulips around the world that you’re fascinated by? In Turkey a tulip is called Lale. The European terms (among them Dutch tulp, German Tulpe, Spanish tulipán, English tulip) probably derive from tülbend, the Ottoman Turkish for 'turban', because of the obvious similarity in shape or perhaps because it was the fashion for a sultan to tuck a tulip into the folds of his head covering. They were worn in turbans as a sign of power and wealth probably, and certainly in the Ottoman empire the ultimate in success in life was having these flowers growing in your garden. And then I guess having the audacity to actually pick one of them and wear it on you as well.

In the period called tulip mania – 1634 to 1637 - the power of the tulip economically was greater than any other currency in the world at that time. the extent that it would have been cheaper to have Boschaert paint you a flower still life than to own one of the most valuable bulbs. I think I’ve really been growing them in the wrong age. Thing about how many Dutch old masters I could buy with them now!

Dutch Historic Tulips. Duc van Tol. Photography by Andrew Montgomery (page 135) Far left and centre right: T. ‘Duc van Tol Salmon’; centre left: T. ‘Duc van Tol Red and Yellow’; far right: T. ‘Duc van Tol Scarlet’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Dutch Historic Tulips. Duc van Tol. Photography by Andrew Montgomery (page 135) Far left and centre right: T. ‘Duc van Tol Salmon’; centre left: T. ‘Duc van Tol Red and Yellow’; far right: T. ‘Duc van Tol Scarlet’. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Can you tell us more about tulip mania? Well there had been other manias. There has been a hyacinth mania, so it’s not the only mania. But that economic period was fascinating not just because it was the first financial bubble or futures trading period but also because it was very democratic – anybody could have a go. And people could buy one bulb. You had socially mobile tradespeople who were investing for the first time.

So the great appeal was the fact that it wasn’t that anybody could afford, say the Semper Augustus, which was the most expensive bulb ever sold – there was said to be only 12 of them – but that you could afford to buy a lesser breeder, and that lesser breeder might break into something like the Semper Augustus, which would make you richer than any of your peer group (the Semper Augustus bulb reached the price of a house).

I think that it was the mystery behind it. And nobody knew what it was caused by, this magical process by which whereby a plain coloured flower one year would then become this extraordinary stratified or variegated one the next. They didn’t know what was causing them to ‘break’ (a broken tulip is one with ‘stripes’ of varying colour). There were all sorts of theories. They would sprinkle powders and strong pigments over the soil thinking that the colours would be absorbed by the bulb and the future bloom would be that colour. Or they would graft slices of different red together with a white one. Whatever they did it seemed there were no guarantees.

Annual tulips for cutting, in the coach house. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Annual tulips for cutting, in the coach house. Photography by Andrew Montgomery Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

It was only in 1927, with the advent of modern microscopes, that Dorothy Cayley at the John Innes Horticultural Institute discovered that ‘breaking’ was caused by aphids, which would feast on one flower and then hop onto the next. And they would transmit what we call TBV, or tulip breaking virus.

So it was this unknown magical element to it that attracted people, combined with the fact that money could be made quickly, and the fact that they were a largely new product coming along the silk route, along with textiles or spices or whatever else through the Levantine areas, and ending up in Holland. So at that time it was new and very exciting and really exotic. Think what it was like in the low countries at that time and then, suddenly, there’s this explosion of colour and form in the tulip.

That’s the past, how's the future looking? I find that really difficult. The might of the Dutch flower industry where these tulips are grown in their millions, or the equivalent in the UK where they are grown hydroponically in big greenhouses in the Midlands, means they are churned out so cheaply that it makes a product like mine - if you can even call it a product - less viable. But there’s a new vogue for British-grown flowers, and local and organic, and the environment. I think that will work in the favour of the tulip. I hope by doing what I’m doing on a small scale it will give people - whether they are gardeners or growers - the confidence that they can do it and the realisation that there’s this enormous palette out there for them to play with.

Species Tulips for Containers. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. Clusiana var. Chrysantha. Synonyms: T. clusiana f. diniae, golden Lady tulip, Persian tulip. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

Species Tulips for Containers. Photography by Andrew Montgomery T. Clusiana var. Chrysantha. Synonyms: T. clusiana f. diniae, golden Lady tulip, Persian tulip. Bayntun Flowers, Wiltshire, UK

What can readers do to make their own tulip-growing more successful? Incorporate horticultural sand (sharp sand) in your growing mix, by mixing it in with potting compost. Protect them against squirrels with chicken wire over the top, or some sprigs of holly, or even sprinkle some chilli powder around for big outdoor plantings.

Try growing species tulips which you can grow in containers or in the ground. They’re just a little bit different and are now more readily available on the market. Experiment with some of the so called French tulips such as Maureen, Dordogne and Menton which are unbelievably tall and strong with strong saturation of colour and invest in some of the viridiflora or Lily flowered if you want to encourage them to come back year on year. And water from underneath the foliage – especially if you’re putting feed in , because if you sprinkle from the top it can stain the tulips. So go underneath with the watering can. And use organic seaweed feed.

Take a look at The Tulip Garden: Growing and Collecting Species, Rare and Annual Varieties.