Our Game Changers co-author on how gaming changed his life (and maybe yours too)

Simon Parkin on the designers changing video games, the most addictive game ever, and why we need to preserve them before they disappear

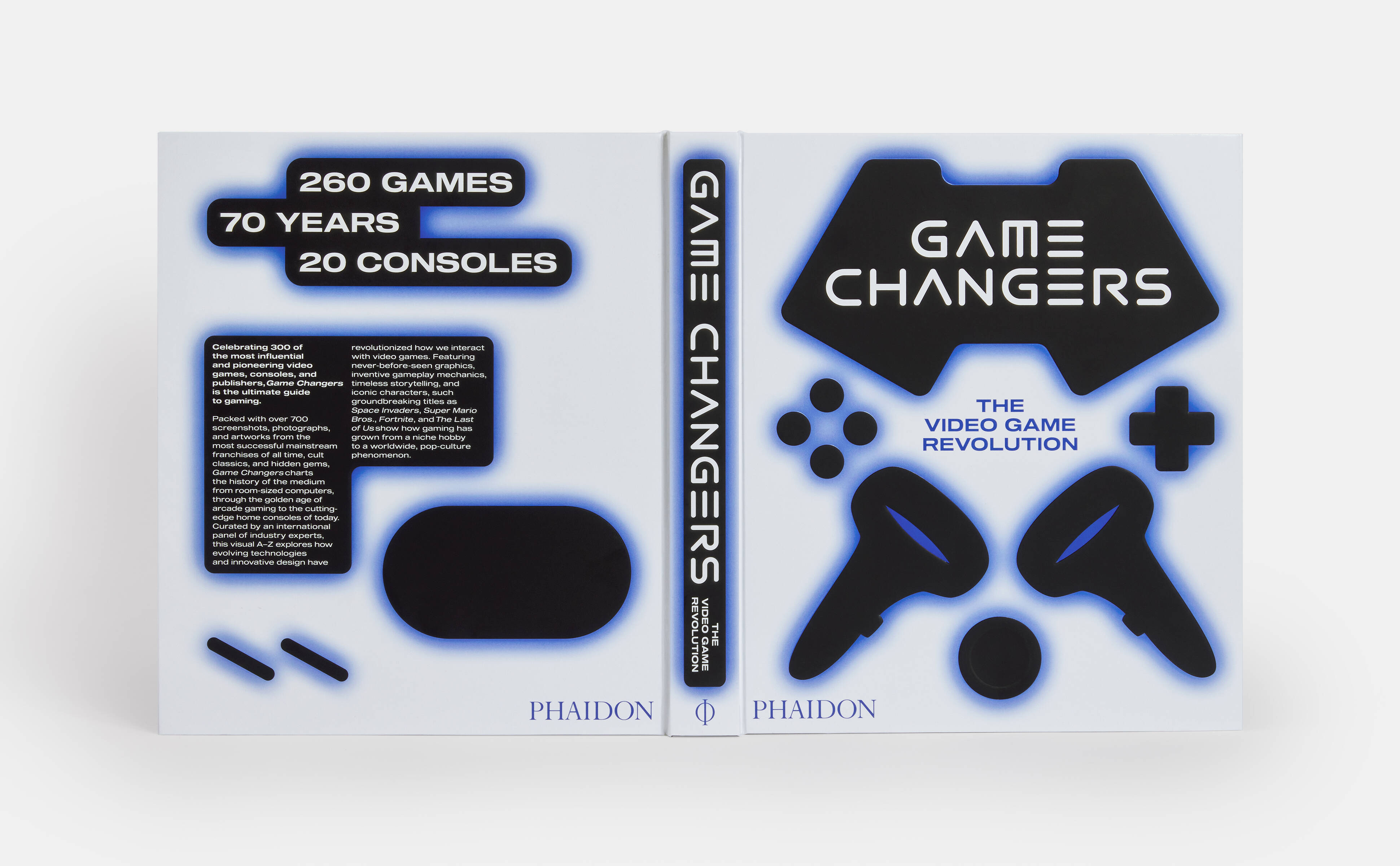

Our new visual history of video gaming, Game Changers: The Video Game Revolution, features 300 entries that celebrate the most significant, influential, and ground-breaking games, consoles, publishers and more, from the first games ever produced back in the 1950s through to the present day.

Each of the 300 entries, including both mainstream AAA titles and indie releases, have been hand-picked by an international panel of industry experts and are illustrated with over 700 high quality images.

A short text informs the reader about each game and its history, and defines what makes it revolutionary, from the never-before-seen graphics of Cyberpunk 2077 to the unique, motion-controlled gameplay of the Nintendo Wii and the unprecedented financial success of Minecraft. These icons of video game culture are true game changers.

In Game Changers, Simon Parkin, an award-winning author and journalist who reviews the year in video games for The New Yorker, sets the scene with an overview of gaming history that explores how iconic games have pushed the boundaries of the medium.

Meanwhile, India Block, deputy editor of Disengo, a leading quarterly design magazine, challenges the idea that video games can’t be art, and discusses how games foster a unique community with a strong focus on design.

We caught up with Simon recently and asked him some questions about the book and about his own video game journey.

Game Changers author Simon Parkin

Game Changers author Simon Parkin

Could you name one ultimate game changing video game - the Citizen Kane of the gaming world? There are quite a few video games that had a significant effect on creativity and design in the industry: Tetris, Super Mario Bros., Doom, P.U.B.G. are all worthy candidates. Perhaps, however, Minecraft is the most significantly disruptive game yet made: it showed that a game with rudimentary graphics, player-directed goals, and a creative, rather than destructive soul, could become one of the most popular and profitable video games in the world. It was, therefore, both artistically and economically significant.

What was the first game you played and what effect did it have on you? My parents viewed video games as a perilous hobby, a distraction that would surely lead to a life of truancy and despair. This, predictably, gave video games something of an illicit allure in my mind. On Saturday mornings, after my brother and I played sports in the local leisure centre, we would watch the older kids huddled around on a Golden Axe arcade machine in the bar area, and wish that we could join in. Games seemed to be everywhere, yet also infuriatingly out-of-reach.

After much pleading, my parents and I reached a tearful compromise: they would buy me an Atari XE computer, something ostensibly with educational value, but which could also play video games. When it arrived, the machine came with a tape deck and two cassettes filled with old arcade classics and text adventures. I would load the games into the machine on these tapes, listening to the tinny screech of the data transferal. Sometimes the game would fail to load properly so, even before you started playing, there was peril involved.

Lumino City, 2014, UK, developed and published by State of Play Games. Picture credit: Courtesy of State of Play

Lumino City, 2014, UK, developed and published by State of Play Games. Picture credit: Courtesy of State of Play

In my later teenage years my parents had an abrupt divorce. At that time video games provided something of a soothing escape; broken worlds which could be easily mended provided if I followed the rules and dutifully ticked off the to-dos. That’s probably the point at which the medium switched for me from an agreeable hobby to an irresistible obsession.

Was there a game you became addicted to? Video games can be highly compelling and are often designed in ways that encourage obsessive, repetitive behaviour –– but only in similar ways to a well-crafted novel, or a Netflix TV series. I prefer to not refer to them as ‘addictive’ as that word suggests specific chemical or clinical properties.

But have I ever been hooked on a video game? Absolutely and repeatedly. For me, the most enriching video games are those that draw you back for their intrinsic rewards (the joy of exploring and mastering their challenges), rather than extrinsic rewards (some virtual currency awarded in exchange for logging in that day).

As I write this, I enjoy playing Call of Duty: Warzone with my sons, Starfield in the evenings, and I usually log into Wordle every morning as part of the daily routine that brings me a sense of comforting predictability in unsettling times.

Dorfromantik, 2022, Germany, developed and published by Toukana Interactive. Picture credit: Steam / Moby Games / © Toukana Interactive

Dorfromantik, 2022, Germany, developed and published by Toukana Interactive. Picture credit: Steam / Moby Games / © Toukana Interactive

Where is gaming going right now? One undeniable fact is that the middle-ground of video games has been wiped out in the past decade or so, leaving mainly the plucky, modest-budget indie projects and the expensive blockbusters occupying either end of the spectrum.

At one time the release schedules were filled with curios and weirdo projects (the Dreamcast and PlayStation 2 were breeding grounds for these unusual, often ground-breaking games) that benefitted from powerful technologies and experienced artists, but which could be made cheaply enough that they didn’t have to compete with, say, the latest FIFA or Call of Duty.

Manifold Garden, 2019, USA, developed and published by William Chyr Studio. Picture credit: William Chyr Studio LLC

Manifold Garden, 2019, USA, developed and published by William Chyr Studio. Picture credit: William Chyr Studio LLC

Experimentation is a high-risk, high-reward game, but a company like Activision, which has voracious shareholders, is more likely to cleave to bankable designs and franchises. So, we are increasingly seeing that the indie game space is where the experimentation occurs.

When an idea in the indie space proves successful, the major studios usually seek to adopt or modify those designs into their ongoing projects. It’s a slightly lamentable situation. My hope, at least, is that a major studio chooses to tackle a more serious, perhaps historical setting, and finds ways to allow the player to enact change beyond expressions of violence.

Lumino City, 2014, UK, developed and published by State of Play Games. Picture credit: Courtesy of State of Play

Who are the designers you respect, and what are they actually doing? With blockbuster games made by vast teams it’s tempting to attribute credit to whomever is the public face of the endeavour: Hideo Kojima, Shigeru Miyamoto, Neil Druckmann and so on. While the creative fingerprints of these individuals are clear in every Metal Gear Solid, Super Mario Bros., and The Last of Us, the risk is that one overlooks the anonymous talents who realised and refined those visions; after all, it usually takes a village, or even a citadel, to raise a video game.

Still, I particularly admire the work of Fumito Ueda (Ico, Shadow of the Colossus, The Last Guardian) whose games feel like the result of an artist’s singular clarity of vision and originality. Even so, I am sure Fumito would be the first to admit his work is facilitated and enhanced by those creatives with whom he has collaborated.

Monument Valley, 2014, UK, developed and published by ustwo Games. Picture credit: Moby Games / USTWO Games

Monument Valley, 2014, UK, developed and published by ustwo Games. Picture credit: Moby Games / USTWO Games

Is the gamer demographic changing, and, if so, what do you think might be driving that that? As video games broaden in scope, and those who grew up playing them move into middle-age and beyond, it’s inevitable that the demographics will shift. It’s often said that everyone plays video games in one form or another, whether that’s doing the Wordle puzzle alongside a morning cup of coffee, playing Candy Crush on the daily commute, or staging a complex, multi-person raid in Destiny late into the night.

Perhaps this is a little overstated, though. Video games in the traditional sense of complex, in-depth challenges and systems played on a computer or console still require a fair bit of geeky commitment and energy – sometimes just to get them set up and working.

This will always limit the audience somewhat (and there will be people for whom real life is already challenging enough, without adding a further to-do list of fabricated, fictional tasks). But after social media, video games are surely the dominant form of human entertainment and will likely remain as such for our species’ lifespan.

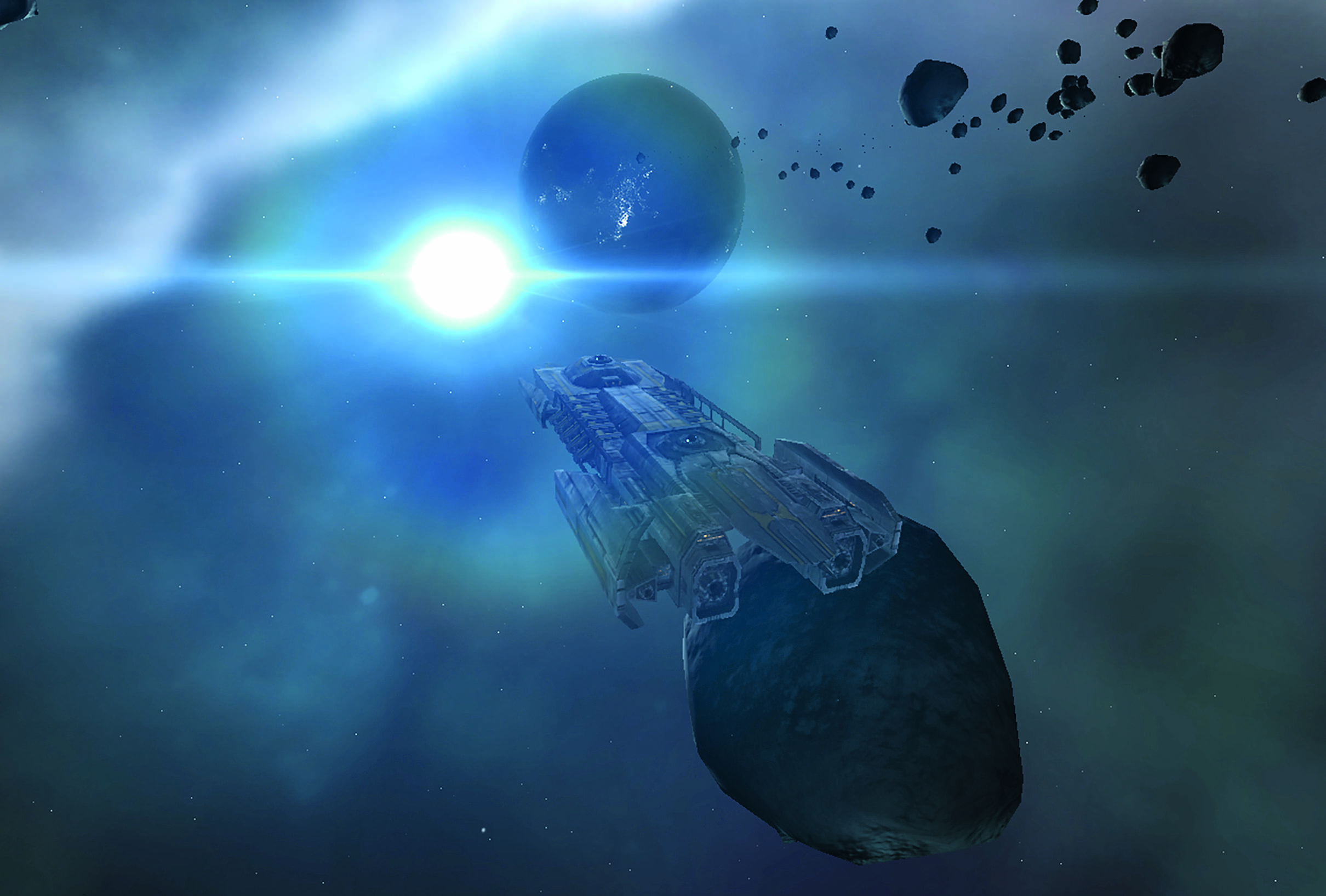

EVE Online, 2003, Iceland, developed by CCP Games, published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. Picture credit: Moby Games / EVE Online © 2023 CCP ehf. All rights reserved

EVE Online, 2003, Iceland, developed by CCP Games, published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. Picture credit: Moby Games / EVE Online © 2023 CCP ehf. All rights reserved

Are video games as profitable as ever or have they peaked? Video games were quick to industrialise, and the economics of game-making have always, to one-degree or another, shaped their creation and design. Early arcade games were designed to scale their challenge so that all but the most gifted or practised player would be bested or overcome withing two or three minutes of play, at which point they would have to space for the next paying player in line or feed the cabinet another credit.

Then, for a long while, video games worked like books or DVDs: all the cost was front-loaded, and the publisher made their money in a single dollop at point-of-sale.

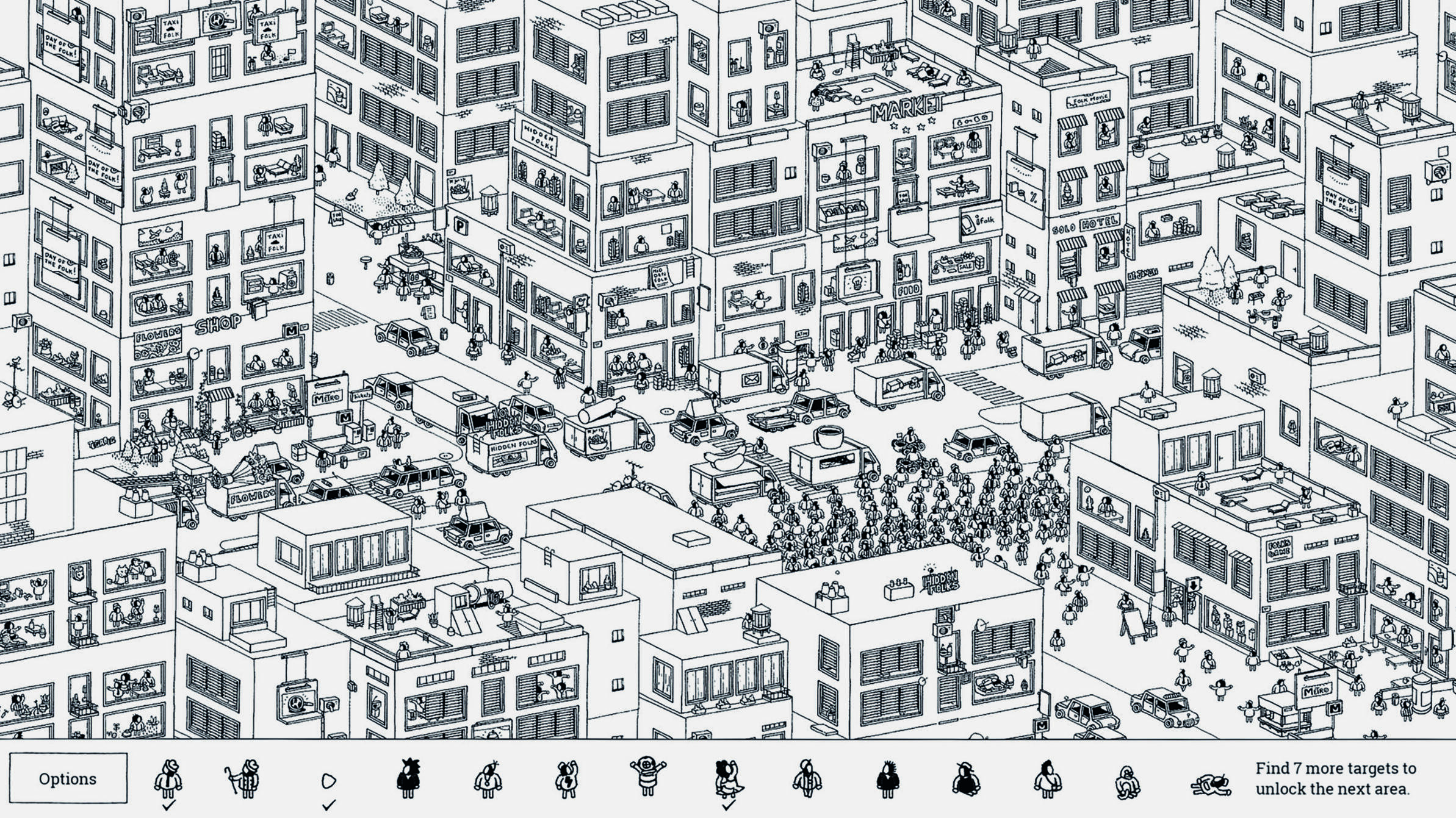

Hidden Folks, 2017, The Netherlands, developed by Adriaan de Jongh and Sylvain Tegroeg

Hidden Folks, 2017, The Netherlands, developed by Adriaan de Jongh and Sylvain Tegroeg

These days there are multiple funding models according to where the game is situated. There will always be big, single-player blockbusters that sell for a large, one-off fee (perhaps supplemented with additional, purchasable chapters further down the line).

By contrast, games like World of Warcraft and Final Fantasy XIV use a subscription model, whereby players are charged monthly for access to the world. And Fortnite helped pioneer another, now dominant model of funding, where the game is free-to-play, but you need to purchase a ‘season pass’ to unlock digital goodies like character skins and weapons, to show off to other players in the game. All these models work well for different kinds of games, and happily co-exist for now.

INSIDE, 2016, Denmark, Created by Arnt Jensen. Developed and published by Playdead. Picture credit: INSIDE. Playdead, Arnt Jensen, 2016

INSIDE, 2016, Denmark, Created by Arnt Jensen. Developed and published by Playdead. Picture credit: INSIDE. Playdead, Arnt Jensen, 2016

Have video games had an overall good or bad impact on society? Both things are surely true. Video game design traits can be seen in so-called ‘gamified’ systems in the real world, perhaps most obviously in social media platforms and fitness apps, where you receive digital rewards for maintaining ‘streaks’ and so on.

Video games have had a profound effect, too, on our leisure activities – first driving people into public spaces to play arcades, then bringing them back into the home to play alongside friends after a night at the pub or, these days, online with friends made around the world.

They have probably contributed to making us more sedentary, and have certainly lured people away from passive media, which had had knock-on effects in terms of lifestyles and related entertainment industries.

They’re also responsible for facilitating friendships around the profoundly human act of play, and at their most beautiful and enriching, can bring us together, not only to compete, but also to collaborate.

EVE Online, 2003, Iceland, developed by CCP Games, published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. Picture credit: Moby Games / EVE Online © 2023 CCP ehf. All rights reserved

EVE Online, 2003, Iceland, developed by CCP Games, published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. Picture credit: Moby Games / EVE Online © 2023 CCP ehf. All rights reserved

Video games were once blamed for all the ills of society (now its social media). Has this lessening of media interest had any discernible effect on their content? Partly it’s due to the ubiquity of video games: it no longer makes sense for politicians and newspaper editors to demonise video games because a major section of their audience probably plays them regularly. Plus, of course, politicians and editors are increasingly likely to have grown up playing video games themselves, so feel more understanding and connected to the medium.

Still, years of seeing video games demonized – particularly in the US, where politicians funded by the gun lobby are always eager to find scapegoats in the aftermath of a gun-based tragedy – has made many video game hobbyists overly sensitive to criticism. It's important to be able to critique games with clear-eyed honesty, to debate their strengths and shortfalls and, perhaps, where their designers might do more to enrich the lives of their players.

As in so many spheres of life, this kind of nuanced discussion has been squeezed out by the digital platforms on which we spend so much of our time, and which profit from spittle-flecked division rather than constructive dialogue.

A Series of Gunshots, 2015, Canada, developed and published by Pippin Barr and Rilla Khaled. Picture credit: courtesy of the artist

A Series of Gunshots, 2015, Canada, developed and published by Pippin Barr and Rilla Khaled. Picture credit: courtesy of the artist

By their nature video games are more ephemeral than other media, does the lack of a preservation mechanism for them concern youn? Game preservation continues to be a subject of much ongoing concern and debate. A recent report by The Video Game History Foundation found that 87% of video games released before 2010 are no longer commercially available.

Tens of thousands of works, many of which represent key moments in the medium’s evolution, are currently unavailable. In my view this represents a sorrowful loss of source material, not only for the people who worked on those games, but also for historians and archivists, and any young player who might wish to enjoy interactive works created in different socio-political circumstances, against different technological constraints and fashions, and within different market conditions.

Monument Valley, 2014, UK, developed and published by ustwo Games. Picture credit: Moby Games / USTWO Games

Monument Valley, 2014, UK, developed and published by ustwo Games. Picture credit: Moby Games / USTWO Games

Video games are often closely tied to the format for which they were first made, and porting them to modern hardware can be difficult, or not financially viable for the companies that own them. The technology for distributing books and films is, by contrast, straightforward and mostly unchanging. Every video game system is different, so bringing, say, a Sinclair Spectrum game to a current PlayStation console requires various acts of technological reshaping.

In many cases the companies that published the original games no longer exist, so it’s not always clear who owns the copyright. These factors and others mean that the industry has been particularly poor at celebrating and contextualising its past, in a way that is deeply frustrating for those of us who believe the medium is worth documenting and preserving.

With over 700 stunning images, this appealing guide to gaming will appeal to hardcore and casual gamers alike, as well as anyone with an interest in design and popular culture. Buy it here.