The Japanese interior bringing brutalism to the beach

Poured concrete isn’t just for US public buildings and European car parks. In Japan, it also suits a naturalistic, seaside retreat

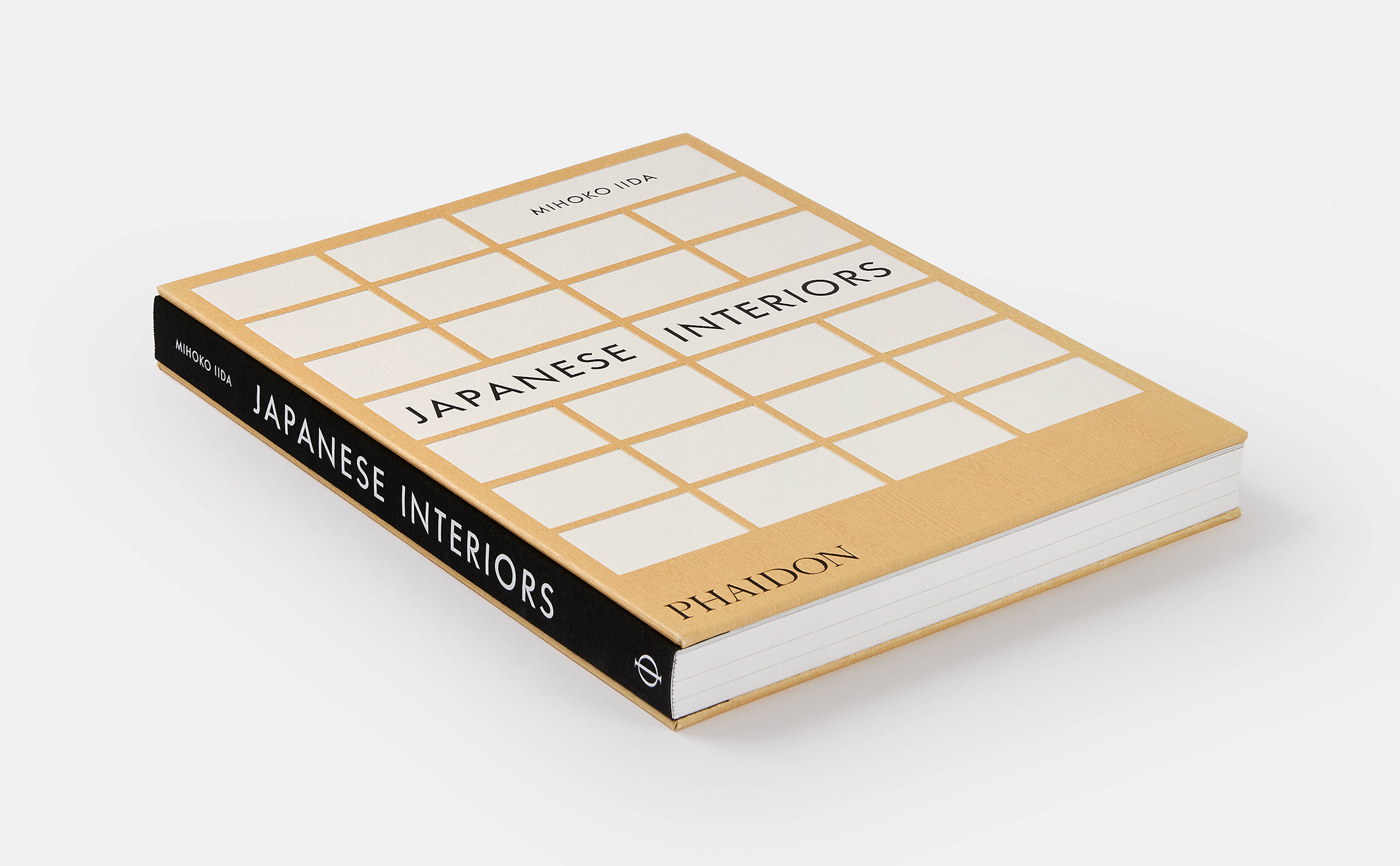

Japanese Interiors offers readers an insiders’ view of one of the world’s most innovative architecture and design scenes. The book is by Mihoko Iida, executive features editor of Vogue Japan, and is the first title written from a cognoscenti's perspective to explore Japanese residential interior design across all genres, all in one volume.

This means Iida is able to explain and contextualise domestic styles and developments for an international audience. Yet, the author is also great at writing about how overseas influences found a home here too.

“Brutalist architecture is said to have originated in the UK after World War II,” the book’s glossary explains. “However, the heavy usage of raw concrete in harsh geometric designs soon lost its popular appeal in the West, while a handful of influential architects in Japan embraced the style as a symbol of Modernism and the future of urban design. Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, who was instrumental in the postwar reconstruction of Japan, was heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect and proponent of the Brutalist movement in Europe. The imposing and complex concrete structures were perhaps what the Japanese people in the postwar era needed to see to believe they were in fact moving forward and away from the simple and traditional wooden structures of the past.”

Pages from Japanese Interiors

By way of example, Iida includes the Peninsula House (top), built by Mount Fuji Architects Studio in the Kanto region – an area that includes greater Tokyo. The house, as Iida puts it, “has a brutalist simplicity to its form: approached from the rear, the minimalist facade consists of a window-less reinforced concrete block, its lower third dynamically slashed with a sharp diagonal line and a cut-out front door. In contrast to the blind-walled approach, the interior spaces of the L-shaped structure are flooded with light on the coastal side due to double-height walls of windows framing cinematic sea and sky views.”

But far from being a bold expression of late modernism (as brutalism was in much of the West), this home “evokes a contemporary take on shakkei, the Japanese concept of scenery borrowed from nature, as is often seen in traditional garden design—with the seascape surrounding the residence stealing the show as its most defining interior feature.”

This is no ‘machine for living in’ as Le Corbusier once put it, but instead offers a naturalistic take on brutal concrete. Our new book quotes the house’s architects as saying they conceived the Peninsula House as a feature of the landscape itself, thinking of it as if “a rocky mountain on the peninsula has been carved out.”

Japanese Interiors

To see more of this home and many more equally interesting interiors, order a copy of Japanese Interiors here.