The wild, early days of the turntable revolution

The nascent, pre-electric days of record players was a time of murky-sounding folk songs, laws suits and truly bizarre ways of putting the needle on the record

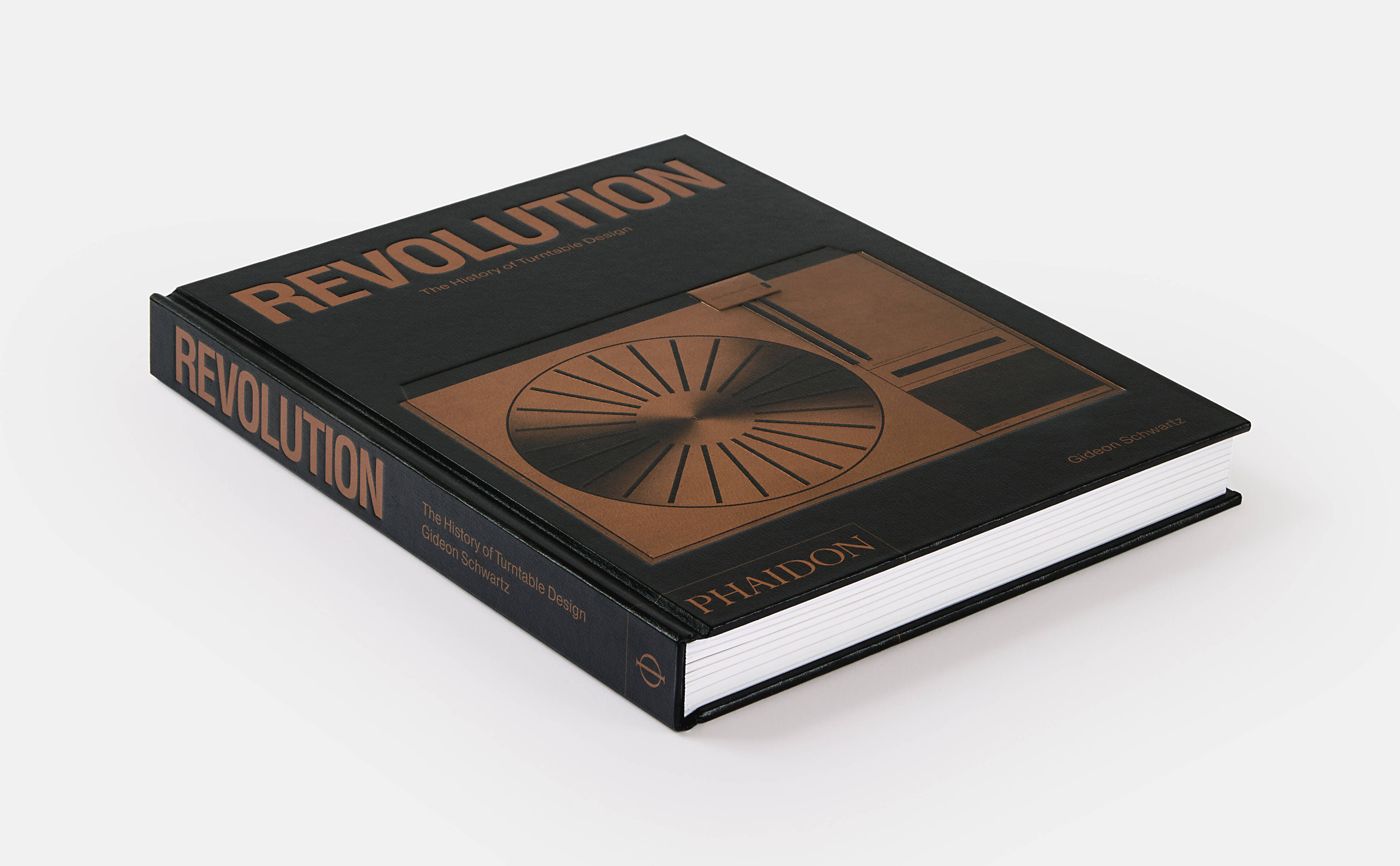

The history of turntable design is written in vinyl, wax, and, perhaps most surprisingly, in soot. This is one of the earliest insights in our new book, Revolution: The History of Turntable Design. Its author, the founder of the ultra-high-end NYC, audio equipment company Audioarts, Gideon Schwartz, takes readers from the earliest attempts at sound recording, right through to the most advanced record players created today. Many of us may think we know early accounts of laying sound onto wax cylinders; Thomas Edison is widely credited as the inventor of the first phonograph, in 1877.

However, Schwartz takes us back a little further, to the Frenchman Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville who, in 1857, built a machine called the phonautograph, which etched soundwaves onto soot-blackened glass or paper. The hand-cranked device wasn’t meant to play a recording back; instead these scratched waves were meant to be ‘read’, visually, like a text; you could think of the device as a cross between a stenograph machine and an early camera.

Though the inventor abandoned work on the machine, many years later, in 2008, scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, unearthed one of Scott de Martinville’s paper-recorded phonautograms of the eighteenth-century folk song Au Clair de la Lune.

“Using digital-imaging technology to convert the ancient code to a digital file, they succeeded in extracting sound from the soot-blackened phonautogram,” explains Schwartz. “Played back a century and a half after being recorded, ‘the voice, muffled but audible, sings, “Au Clair de la Lune, Pierrot répondit’ in a lilting eleven-note melody—a ghostly tune, drifting out of the sonic murk.”

Portable Gramophone (with Geisha Reproducer, C. H. Gilbert & Co.), c.1920

From that point onwards, the race and rivalries to properly reproduce sound via rotating wax cylinders, like Edison, or spinning discs, a method preferred and popularised by Edison’s rival, the German-born, US-based inventor, Emile Berliner, who applied for his ‘gramophone’ patent in 1887.

Berliner was not only a notable physicist and inventor, he was also a prescient businessman, as Schwartz explains. “Simultaneously with developing a machine, Berliner put equal emphasis on improving the quality and fidelity of disc records along with the stamping process, laying the duplication groundwork for the record industry to follow,” writes the author. “He argued that his motivation was to make as many copies as desired from an original recording. And flowing from that he reasoned, ‘Prominent singers, speakers or performers may derive an income from royalties on the sale of their phonautograms.’ His impassioned insight into the medium as entertainment with mass appeal served as a major catalyst for the gramophone’s market resilience and eventual success over cylinder-based machines.”

Nevertheless, just as in today’s music biz, Berliner’s place within that early record industry hierarchy was far from assured. Around the turn of the century, the American-born inventor and businessman Eldridge Johnson – who had been employed by Berliner – established himself, in terms of engineering skills, technical innovations and manufacturing capabilities, that after legal battles and extensive negotiations, he and Berliner agreed to form a new corporation, the Victor Talking Machine Company, “under Johnson’s management, in which Berliner would receive 40 percent of common stock and Johnson would receive 60 percent.”

Victor’s early, innovative, wind-up machines bear a reasonable similarity to today’s record players. “By 1902, along with Johnson’s many improvements to the gramophone and disc quality, one new feature would stand out: the invention of the tonearm,” writes Schwartz. “Johnson advanced the tonearm in order to permit the coupling of the sound box to the metal horn without having to hold its weight. It greatly reduced disc wear and considerably improved sound fidelity. Victor claimed its new device with the tonearm was ‘the world’s greatest musical instrument.’"

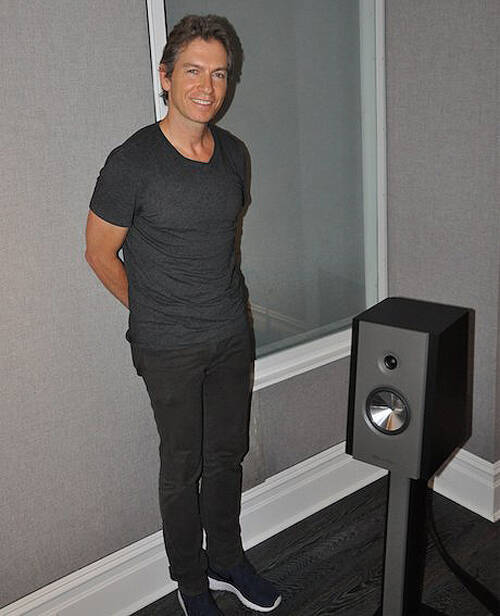

Gideon Schwartz

Meanwhile, many of today’s music lovers will recognise Victor’s canine logo. “Victor’s famous trademark, a terrier dog named Nipper charmingly listening to a gramophone—an image retouched by its painter Francis Barraud from his original painting that featured a cylinder phonograph— would also later serve as the logo for Victor’s British Commonwealth affiliate, His Master’s Voice, or HMV,” writes Schwartz.

Not wholly outdone, Berliner returned to his native Germany to lay down one additional bit of turntable history. “In 1898 he founded Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft, a record label focusing on classical works,” notes Schwartz. “ Continuing to this very day, it has inarguably attained legendary status in classical circles.”

Revolution

To see more machines from this vintage, as well as many more recent record players, order a copy of Revolution here.