The sparky, sonic addition of electricity to the turntable revolution

Our new history of turntable design looks at how the advent of radio briefly overshadowed the record player’s prominence

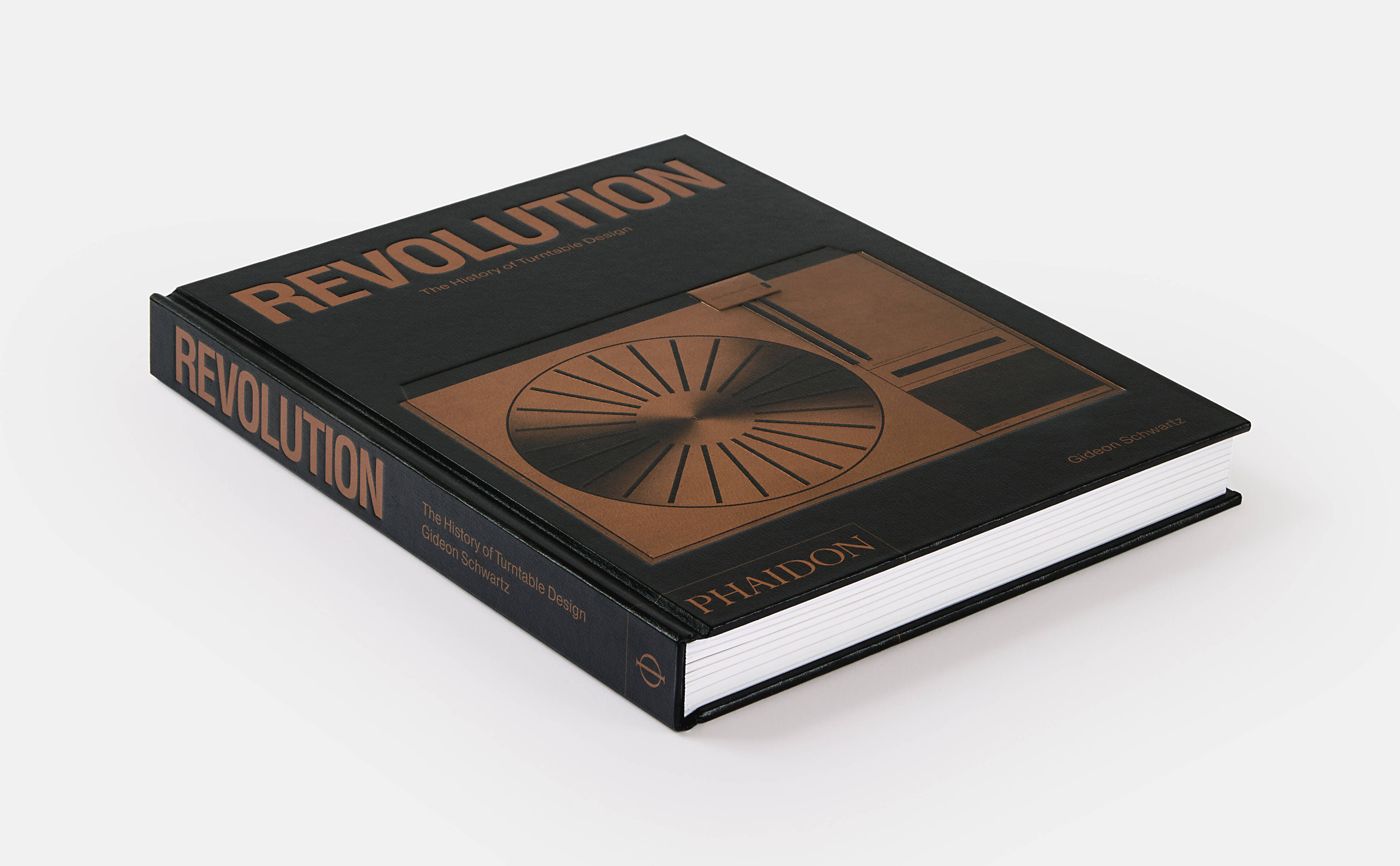

In his book, Revolution: The History of Turntable Design, author and professional audiophile takes us from a time before wax cylinders, right up to today’s analogue renaissance. It’s a wild ride, encompassing pioneering physics, worldwide economic crashes, court battles and an almost never ending quest to perfectly reproduce the music.

You’d think the arrival of electricity would have been welcomed by anyone interested in acoustic high fidelity. However, Schwartz marks the end of the mechanical era (when music was cut directly onto discs, and amplified with the aid of speaking horns), not with a bang, but with a whimper.

“By the 1920s the purest expression of analog reproduction would come to an end,” he writes. “The world would never again witness the mechanical reservation of a sine wave so painstakingly faithful,” adding: “The inevitability of electrical progress ushered in the microphone, vacuum tubes, and, most notably, radio.”

Radio’s prominence in the 1920s and ‘30s doesn’t wholly eclipse the record business. Schwartz notes the arrival of Harry Pace’s Black Swan Records, “the first African American–owned record label in the United States,” as well as the way in which electrical developments such as the microphone, the vacuum tube and the electric speaker (which arose from innovations in telephone technology), had brought greater clarity and scientific rigour to the record player, both in terms of the recordings pressed onto discs, and the quality of their playback, when spun on newer machines.

The author cites a 1926 review from the Sunday Times in London. Its music critic Ernest Newman, who, having lamented earlier mechanical record players and discs, celebrates the accuracy of newer turntables and records. “We get from these records what we rarely had before,” Schwartz quotes Newman as saying, “the physical delight of passionate music in the concert room or opera house. We do not merely hear the melodies going this, that, or the other way in a sort of limbo of tonal abstractions; they come to us with the sensuous excitement of actuality.”

There were also aesthetic innovations, brought by the Art Deco stylings of industrial designers such as John Vassos. However, the rise of radio, combined with the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the World War that followed (when much of the manufacturing capacity used by the music business was turned over to the war effort) led many turntable manufacturers to pair their offerings with wireless sets, such as in the case of the Silvertone radio and record player, which Sears Roebuck & Co. offered in 1938.

Author Gideon Schwartz

Nevertheless, hope lay at the younger end of the market, when new styles of music, and new ways of listening to them, were on the rise. “By the mid-1930s, teenagers were moving away from Mozart and gravitating toward Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington, among other swing-era notables,” writes Schwartz. “These new stars were sought out and signed by the savvy Edward Wallerstein of Columbia Records, serving to revitalise and diversify its catalogue.”

“By 1941—with industry-wide discounting jukeboxes, and a competitive marketplace—prospects for the phonograph were on an upswing,” Schwartz concludes, with images of a couple of classic 1940s Wurlitzer jukeboxes reproduced on the following pages, hinting at the youthquake that was awaiting the record industry in the decades to come.

Revolution

To see those turntables mentioned, as well as many others, order a copy of Revolution here.