The role of Japan in the turntable revolution

Our new book examines how Japanese firms came to offer affordable record decks, and kindled a love of Japanese engineering among dance music enthusiasts

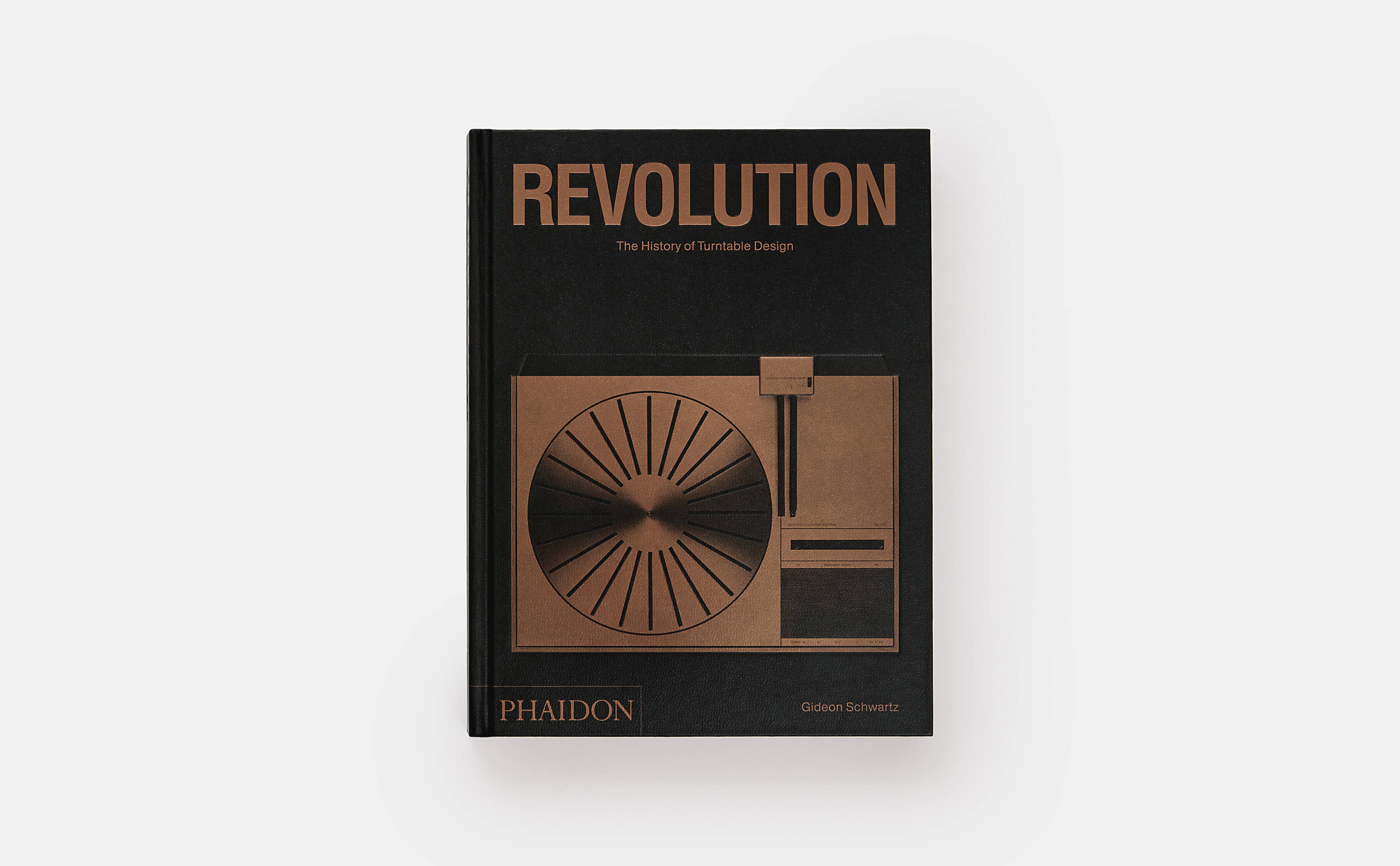

In his new book Revolution: The History of Turntable Design, author and professional audiophile Gideon Schwartz notes that in the 1970s, accompanying a trend for high-end, high-fidelity, beautifully designed record players, there was a very different market tendency. “A country development was emerging in Asia, spawning a multitude of mass-produced cheaper exports,” he writes, “flooding the global market, and making turntables accessible to most consumers.”

These days we associate Asian mass market production with Chinese manufacturing, but back in the 1970s, it was Japan’s factories that dominated this portion of the market, and while Japanese firms may not have had the boutique appeal of some European and American marques, they still contributed a huge amount to record player design and innovation.

Schwarz singles out consumer electronics giant Kenwood for particular praise. “The company’s peak in turntable designs was its 1970s KD series: the most significant example was the KD-500, otherwise known as “the Rock” for its polymer cement-resin plinth,” he writes. “Kenwood’s emphasis on an inert and resonance-free plinth influenced Sharp’s 1975 Optonica model, as well as later stone designs such as J. C. Verdier’s La Platine, Jadis’s Thalie, and various Well Tempered Lab models.”

KD-500 Turntable, Kenwood, 1976

Technics, another innovative Japanese firm, favoured solid plinths, which it paired with its direct-drive mechanisms, to produce sturdy, quick-starting turntables which found particular favour among one particular group within the record buying public.

“Disc jockeys preferred the 1970s Technics SL-1200 turntable,” writes Schwarts, “for it allowed them to mix records with complete speed control: the direct-drive table could instantly return to a set speed after a record was moved back and forth on the platter (the technique known as scratching).

“The table’s quartz-controlled high-torque motor enabled ideal manipulation through scratching and beat mixing, and the solid plinth made it impervious to club resonances and vibrations. With the hip-hop, dance, and techno scenes embracing the SL-1200, the table became a part of the social fabric, in essence preserving vinyl within youth culture and allowing it to sustain the onslaught of digital audio.

“In an effort to determine the origin of the DJs’ love affair for this table, historians like to point to Grandmaster Flash’s record, The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” the author writes. “This single from the grandfather of hip-hop was created, using a Technics SL-1200, from a medley of scratches and LP cuts, all intertwined from two records and coming together not just to create a song but also to give birth to a movement that now dominates popular musical culture.”

Some companies may have ignored or shunned this apparent misuse of their equipment, yet the SL-1200’s designer, Shuichi Obata, positively embraced its novel application.

“In revising the SL-1200 in the late 1970s, Obata met with DJs in order to sensitise the table to their requirements,” our author writes. “As a result, the SL-1200MK2 was reengineered with the club scene as its inspiration. Apropos to its DJ purpose, Technics claimed it to be ‘tough enough to take a disco beat and accurate enough to keep it.’

Revolution

“Obata’s legendary SL-1200 continues to evolve, serving as one of the stronger and most visible catalysts for analog’s revival and renaissance in the 2000s,” Schwartz concludes. To see more of these decks as well as much more besides order a copy of Revolution here.