The clubs that drove Jim Hodges’ Art

New York’s clubs and bars both excited and terrified the artist, as he explains in our new book

Jim Hodges was something of a big city ingenue when he relocated from his home in smalltown Washington State to New York City back in 1983. “New York City life during that period was a mix of excitement and terror,” the artist says in our new book on Hodges. “It was scary and fun. Coming from Spokane, where I was mostly deriving inspiration from hanging out in the woods or at lakes or rivers, and then diving headfirst into this other very social nature of New York City – the creativity and immediacy of it was incredible. I really responded to the grit and the aggression of the city and the dark threatening edges of it. The city introduced contexts and opportunities for me to play with my fantasies and secrets that I hadn’t entertained before arriving here.”

New York’s clubs embodied a lot of that excitement and terror. “I was going to bars and clubs in the East Village, the Meat-Packing district and the area around the Spike and Eagle bars in Chelsea – Trax, Jays, The Locker Room – these were some of the places and the neighbourhoods I’d tour and the ones I found the most alluring,” Hodges goes on to say. “The streets of Alphabet City around Tompkins Square Park fed my imagination too. I was very curious and interested in seeing as much as I could and started discovering more underground experiences and venues for music and performance. The Pyramid Club, Roulette and, of course, The World, Mars, Save the Robots, ABC No Rio, not to mention the sex clubs, bath houses, backrooms: all these were exciting and a little scary, so that combo worked perfectly for me.”

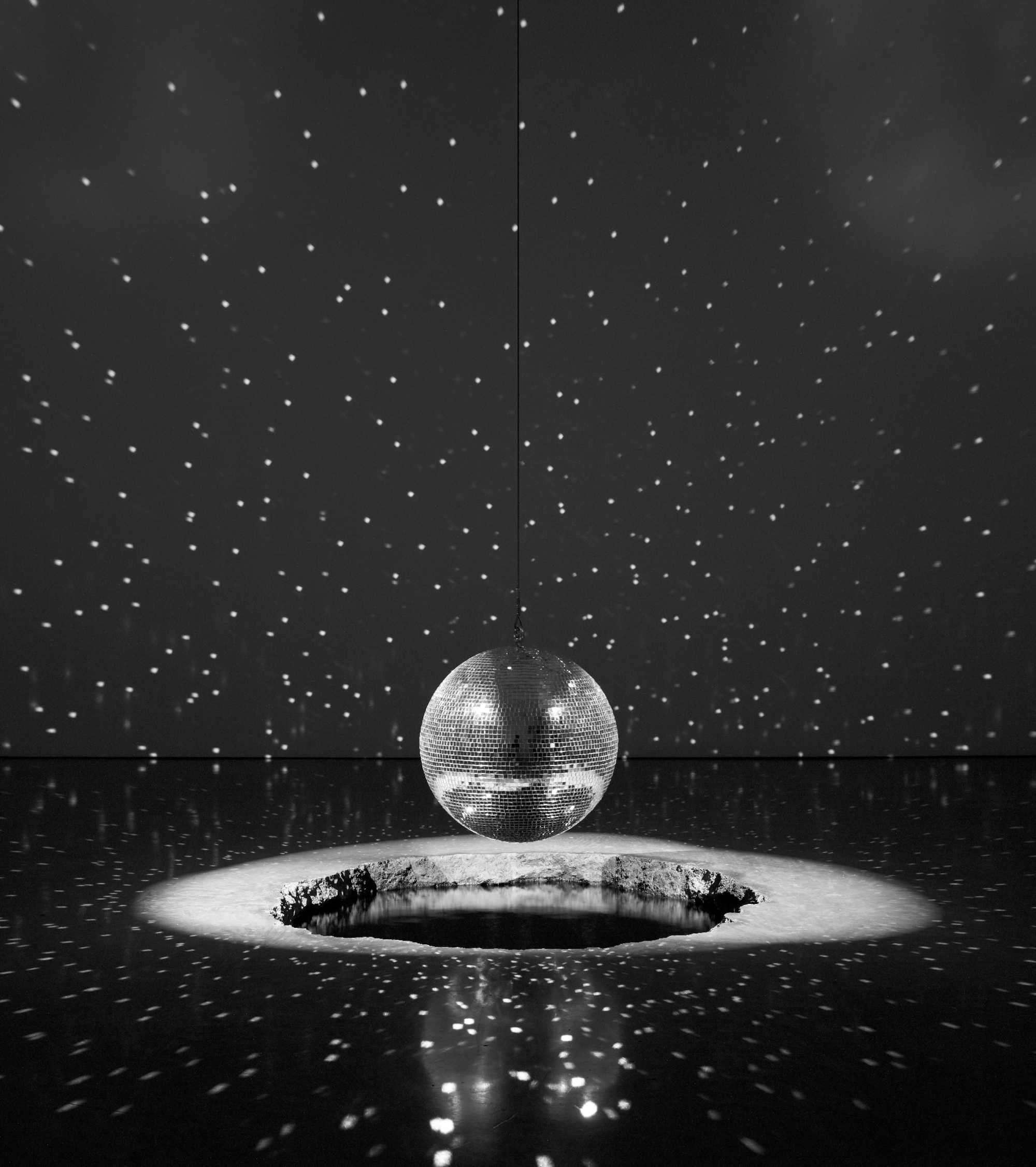

You can detect elements of this dichotomy in much of Hodges work, such as in his 1992 piece, No one ever leaves, consisting of a leather jacket and a spider’s web fashioned from chains, but it’s perhaps most apparent in an untitled installation that featured a large mirrored disco ball, that the artist created for a 2011 exhibition at the Gladstone Gallery in Manhattan. Here’s how the art historian and curator Robert Hobbs describes the work in our book. “Suspended by a cable over a black water-filled hole that had been jackhammered into the gallery’s concrete floor, the spinning disco ball participated in a continuous hour-long cycle as it rose from the pool while still dripping water and started reflecting bright lights across the interior of the room,” writes Hobbs, “which were created by lamps positioned in the four upper corners that moved in tandem with the ball’s ascent and descent.”

Of course, mirrors are a prominent inclusion in many of Hodges pieces since the 1990s; Hobbs argues that their inclusion “sparked an enthralment with their light reflecting qualities.” Yet the artist has acknowledged the mirror ball’s clear symbolic link to club culture, and it’s hard not to see parallels between that bright sphere rising and falling from a dark pool dug into New York City, and that dose of fear and excitement Hodges first felt, entering the city’s night life.

To find out more about the life and extraordinary work of this important contemporary artist, order a copy of our Jim Hodges book here.