Nick Kennedy - Why I Draw

This innovative artist removes human gesture from his drawings, relying instead on machines that recall and parody scientific processes

The UK artist Nick Kennedy’s work uses an altered notion of drawing to explore two seemingly incompatible dichotomies: the subatomic and the infinite. Whereas traditionally the artist’s presence would be communicated by the transformative touch of the pencil on a surface, Kennedy seeks to delete the hand of the artist altogether, replacing it with a number of intricate devices that serve to produce the work instead so that it becomes cyclically auto-generated.

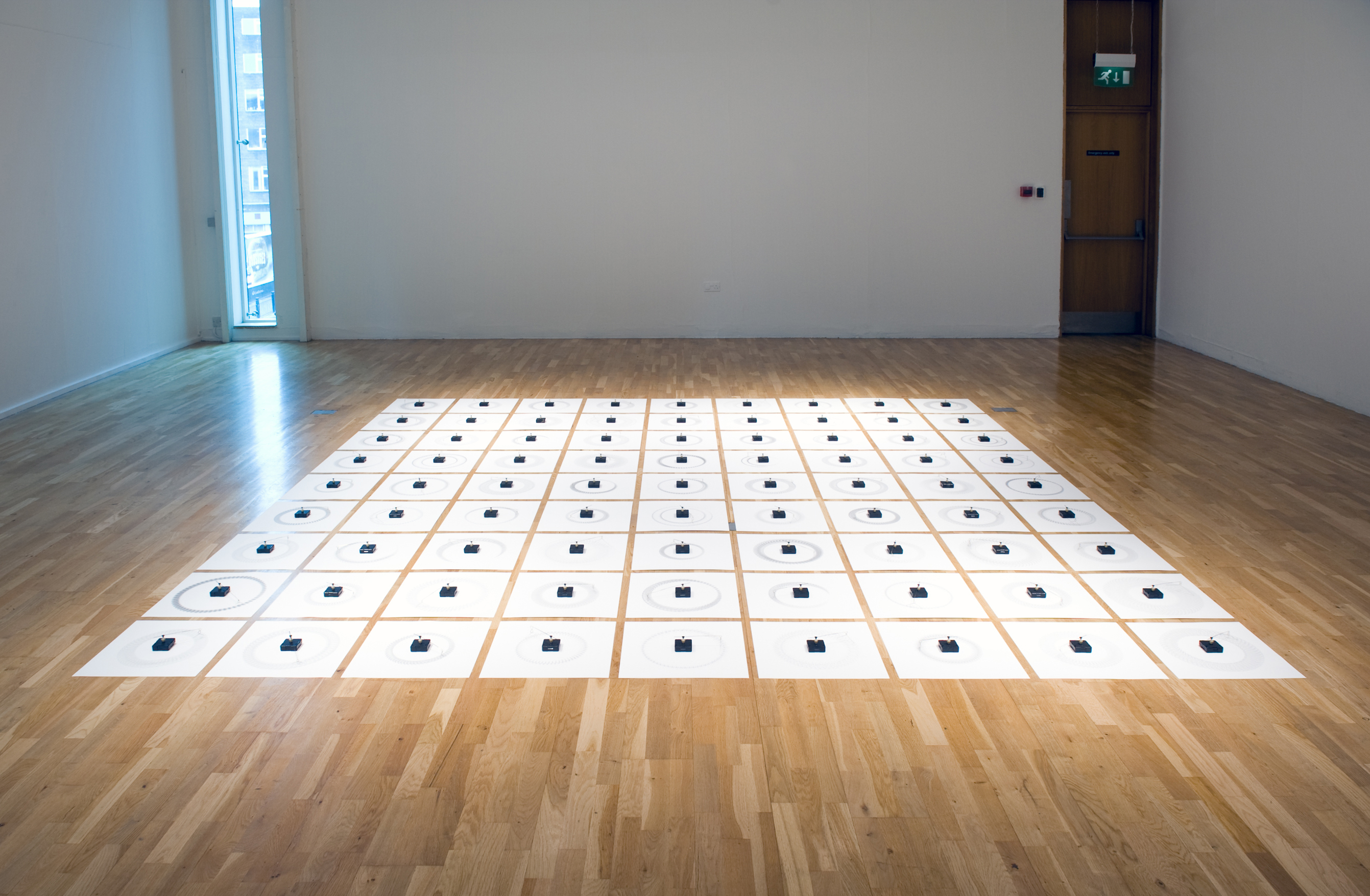

This is beautifully illustrated in Timecasting (2013), an installation of eighty-one delicately balanced drawing mechanisms. Laid out on the floor in a nine by nine grid, each one has its own generative capacity. A central mechanism is built around a quartz clock movement; built on to this are two appendage-like arms, on to which the artist has attached two sets of protuberant, leg-like pieces of graphite (no different from an ordinary pencil drawing set). As they turn on their axis, they give a feather-light touch to the paper below, forming, in most cases, and over a period of time, a densely packed and finely woven piece of drawn circular tracery. In theory, as each machine is identical, each drawing should be the same.

However, each one is totally and distinctly unique, illuminating Kennedy’s interest in the forces of chaos and order. These interests are found and replicated elsewhere in Kennedy’s practice. It is almost as if he uses drawing in a scientific sense, as a way of questioning theories about his chosen material, and to stretch and expand its utility, thereby seeking a deeper substance.

In Truthplotter II (2019) we are presented with another device, this time in the context of a wall drawing. This work also has a dynamic motor at its core that, once set up and primed by the artist, precisely renders a fine line drawing that is almost incised into the wall as it repetitively tracks its previous mark. In this instance the machine loops around to create the infinity symbol – or indeed perhaps it is rendering a kind of Möbius strip, a surface that only has one side and loops back in on itself, so if it was followed there would be no beginning and no end. What we are left with is the drawn equivalent of the solidifying of time, a sedimentation of marks that are the end product of the artist’s machine, but that also articulate analogously his exploration of scale, from the infinitesimally small to the endlessly infinite.

Kennedy is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, our new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We sat him down and asked him a few questions about how, why and when he draws.

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I am an artist based in the north east of England. I'm thinking about the future and how to work in this new altered reality we find ourselves in. I'm currently working with Saturation Point to curate a drawing show in London and I'm planning to make a major new installation for my home town as part of the Middlesbrough Art Weekender. I'm thinking a lot about the place where the physical world meets the digital world, about the relationships between human and machine, time and matter, order and chaos.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? Drawing seems to run through everything I do. I develop 'experiments' that recall and parody scientific processes. I introduce rules and strict parameters into the process of making, which deliberately reduce my presence within the work and challenge my control over it. Throughout my career drawing has offered me a reliable vehicle through which to explore ideas about the nature of truth, agency and beauty. Drawing has a kind of universal quality – the simplest of technologies which, like many humans before me, I have adapted to suit my own purposes. I am always interested in playing with and exploring it’s permeable boundaries to produce something I didn’t expect.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? The position of drawing within the artworld seems to be undergoing perpetual reassessment. I don't think it is medium specific any more and so it is hard to pin down. For many artists, myself included, it is the primary means of expression, though it defies easy categorisation. Maybe we need to stop trying to work out its place and accept it is, as the artist Alan Hathaway has described, a kind of 'attitude'.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? There is always a fine balance to be struck between being in control and letting go. This liminal space in between, where the work flirts with failure is the most exciting, compelling part for me and what drives the work on. It’s difficult to strike that balance and get it right. I find it hard to write about and articulate what I'm trying to achieve in words, which is probably why I am an artist and not a writer. I like what Le Corbusier had to say about drawing - “I prefer drawing to talking. Drawing is faster, and leaves less room for lies”.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? It can be very fast or very slow and sometimes it is both at the same time. There is a natural directness to drawing that provides me with a framework for play, a means of thinking things through and a way of expressing something and getting it out into the world. For me it can also become a process that can be played out gradually and indefinitely - the first of my Timecaster sculptures has been drawing for close to seven years now and I’m not sure when it will stop. Either way it offers the kind of honesty or authenticity I'm looking for.

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something most of us cannot? Children aren't scared to be judged. There is a freedom in drawing that is schooled out of us by the time we become adults. Part of being an artist is trying to unlearn what we are taught and rediscover that freedom. I'll keep trying but I'm not sure it's possible.

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? Drawing is a foundational tool. For around 40,000 years drawing has provided humanity with an immediate means of communication that transcends written and spoken language. The oldest known cave paintings reveal that we were using natural materials to mark shapes and describe forms - perhaps for ritualistic purposes or perhaps for recreation, but long before written languages had been developed. Drawing is rudimentary and sophisticated at the same time. It permeates nearly all forms of culture, from the back of the envelope pencil sketch to the most complex architectural CAD plans. We use it all time and we have done since the earliest days of humanity.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? The place where I find out if it is working is in the studio, which is the place where I get to test ideas and play with stuff. I try to maintain a playful approach to making but I’m obsessive about the details, so there are often a number of revisions or iterations to a piece of work or process for making before I feel it is on the right path. Increasingly I like to make work that responds to specific spaces or contexts, so sometimes you don’t know if it really works until it’s been installed. There is nearly always an element of chance procedure in my work which brings with it a certain amount of jeopardy and possibility that it just won’t work at all. This is what keeps me on my toes and keeps me drawing.

You can see more of Nick Kennedy’s work via his gallery Platform A, on his website, and via his Instagram @studionickkennedy. Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, and Emma Talbot is available now in the store. We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.