African Artists and masks

Our new book demonstrates how the continent’s brightest contemporary artists draw on one of its earliest forms

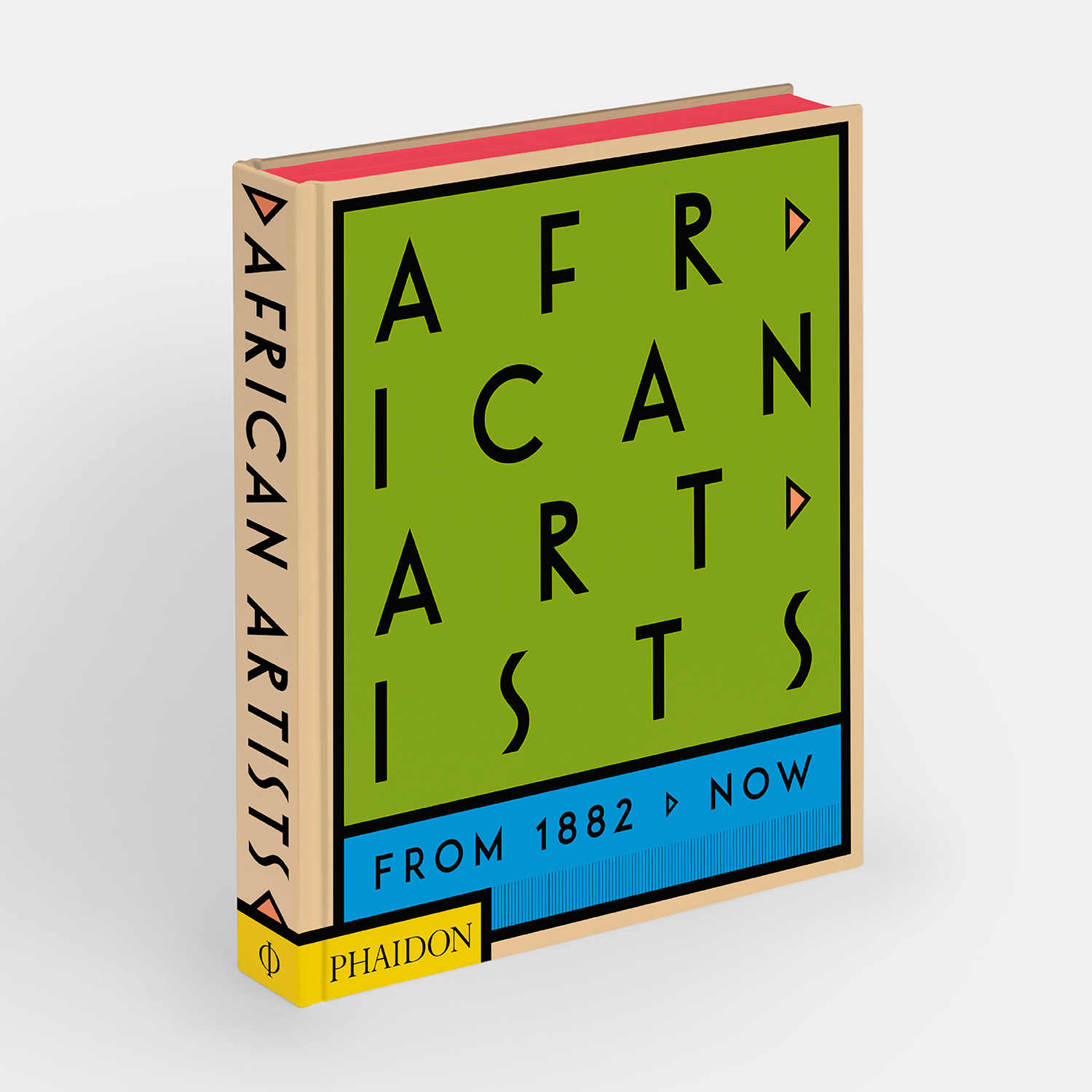

The mask might be the one work of art we all associate with Africa, whether it’s a Benin ivory mask, a wooden mask from Cameroon, or a style of clay mask common in Gabon. Of course, our new book, African Artists 1882 to Now, shows how misleading many of our assumptions are; this beautiful new title profiles 300 modern and contemporary artists born or raised in the African continent. There’s filmmaking, performance art, installations, as well as plenty of more conventional painting and sculpture.

Nevertheless, masks, both as a symbol of African culture, and as an everyday, folk-art tool, recur in many of the works featured within this new book. Some artists, such as the South African-born, British-based Gavin Jantjes, feature masks partly because the form was appropriated by many within the modernist movement.

“A key figure in the 1980s British Black Arts Movement, Jantjes was a member of the Arts Council of Great Britain (1986–90) and developed its national policy on cultural diversity,” explains our new book “It was during this period that he painted Untitled, (above) a commentary on the interplay between African and European art. The constellation-like outline of the central figure of Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), widely celebrated as the seminal work in the development of European modernism, is depicted isolated and floating in space, tied by an infinite umbilical cord to an African mask like those that inspired Picasso, but whose influence he emphatically denied.”

Other artists, such as Kenyan sculptor and photographer, Cyrys Kabriu, combine mask making with more contemporary facial adornments – in this case sunglasses. “Growing up close to a municipal rubbish dump, Kabriu was challenged by his father to create desirable objects out of waste, in particular fashioning his own spectacles, and this favoured motif and do-it-yourself aesthetic continue to inform his practice,” explains our book. “Best known for photographic self-portraits called ‘C-Stunners’ (C standing for Cyrus), Kabiru is integral to these works both as model and as the individual glimpsed behind an adopted persona. The combination of beads, wire, calabashes and the artist’s self-portrait makes for powerful multifaceted work, and his chosen medium of expression emphasizes the idea of repurposing. Drawing on traditional storytelling and more recent genres of Afrofuturism, Kabiru presents complex views of the continent and its identities yesterday, today and tomorrow.”

Others, meanwhile, work in masks in quite a utilitarian way, to facilitate storytelling. Consider the work of the Malian photographer, Fatoumata Diabaté. “A regular feature of the Malian photography scene since 2005, Diabaté’s photographs draw on an oral tradition of stories and tales handed down over the ages,” explains the book.

Though her chosen medium is photography, the artist incorporates more traditional elements such as masks, animal heads and hides, card boxes, clothing and other materials in her images, thereby connecting the stories her photographs tell to sacred, mythical and spiritual orbits, our new book explains. Bala Na Djolo presents a portrait of a man with his face covered by a hand-crafted calabash adorned with spikes representing animal horns,” the text goes on to say. “Showing a close connection between humans and animals, the image reverberates with the stories of ancient Mali.”

To better understand how these works fit into a wider culture of artistic expression, order a copy of African Artists 1882 to Now here.