African Artists and Postcolonialism

Our new book features works that capture the optimism and cultural assertiveness of 20th century independent African nations

African Artists from 1882 to Now is a hugely rewarding book, not least because it offers a considered insider’s view of historical events that many of us have only read about from afar.

This beautiful new book features the work of over 300 modern and contemporary artists born or raised in the African continent. In their work, we can trace the influence of old European empires, the latter day globalisation, civil wars, separatist movements, and much more.

Some of the most ambitious and heartening works reflect the postcolonial period, a time, towards the end of the 20th century, when European empires retreated from Africa, many countries gained independence, and began to enjoy the wealth and cultural prowess once restricted to more developed nations.

As the historian, curator and artist Chika Okeke-Agulu puts it in his introduction to our new book, “By the mid-century modernist art aligned with newfangled ideas about national culture and reclamation of indigenous and Islamic art traditions.

“Inspired by possibilities of independent nationhood, these artists, often working in groups, invented a postcolonial brand of modern art,“ Okeke-Agulu writes. “Broadly, this meant an intensive formal experimentation with indigenous art, craft forms and design, and the association of the resulting modernist painting, prints and sculpture with cultural authenticity and sociopolitical self-determination.”

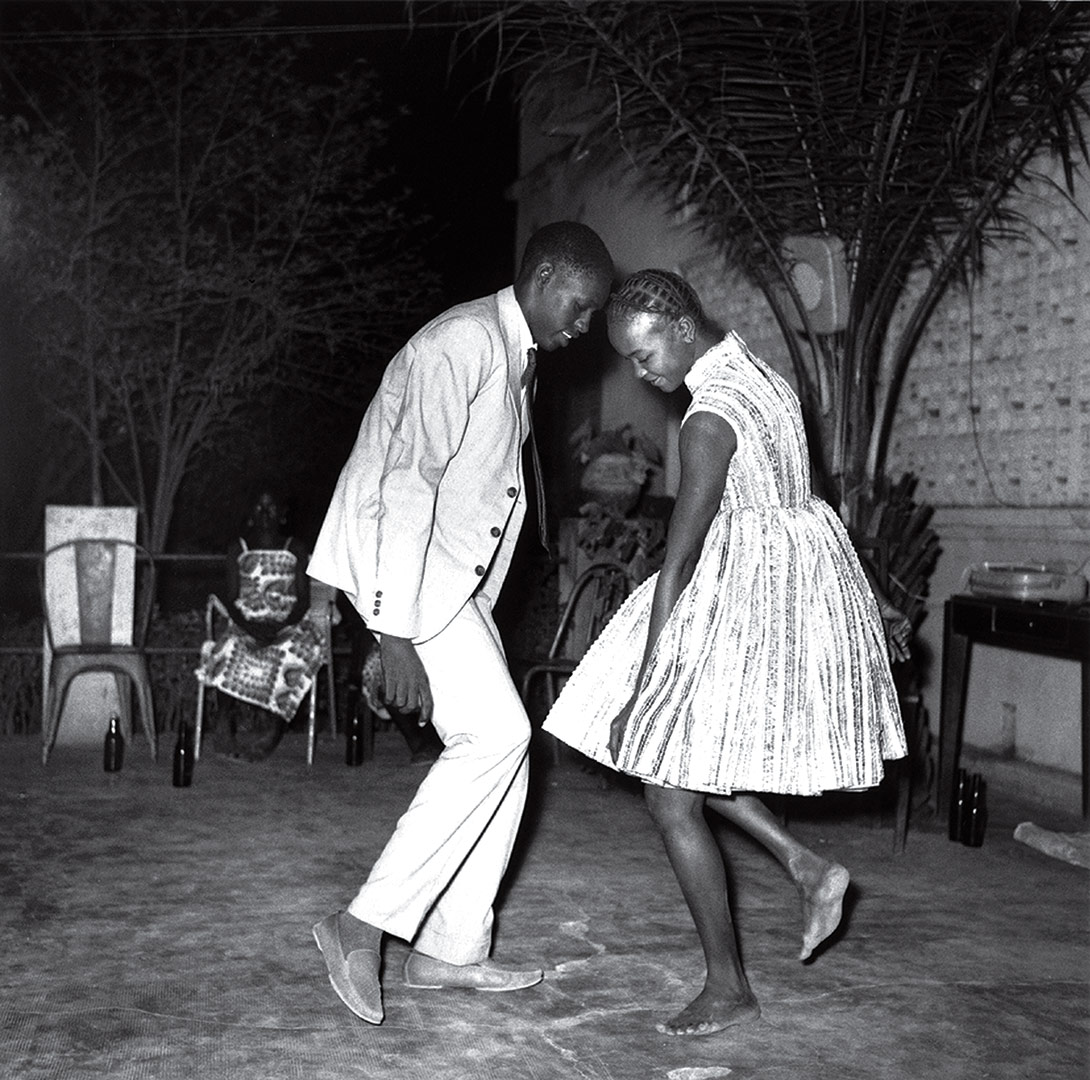

The Malian photographer Malick Sidibé (top image) captured some of the optimism felt in his country, following its independence from France in 1960. “Sidibé himself began photographing in the 1960s, producing lively black-and-white pictures of Bamako nightlife – images that encapsulate the style and culture of postcolonial Mali and for which he became renowned,” explains our new book. “Sidibé was always on the lookout for a sense of vitality, as seen in this photograph – probably his most famous. The timing of the shot, with both dancers having at least one foot in the air, makes the music of the moment almost audible, cementing Sidibé’s reputation as a photographer who didn’t just capture the energy of his subjects but also of their time.”

For an equally impressive black-and-white image, illustrating the modern expression of homegrown culture, let’s turn to the Nigerian photographer, J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere. “Photographing across genres, Ojeikere worked for colonial and national government agencies from 1954 to 1975 before opening his own studio in Lagos, producing both commercial and documentary work,” explains our new book. “His 1968–75 series ‘Hairstyles’ showcases the ephemeral hairstyles Nigerian women wore at special events. Seeking to document a tradition briefly threatened by wigs in the 1950s, but which resurged in the 1960s with an urban sculptural idiom, he acknowledged the ethnographic and aesthetic elements in this series comprising over two thousand negatives.

“The multiple views, blank backgrounds and use of black-and-white film highlight the hairstyles’ sculptural qualities, engineered by plaiting, threading and rolling,” the book goes on.”While earlier hairstyles proclaimed the wearer’s social status, post-1960 independence-era hairstyles drew from varied sources, including architecture and politics. In this photograph, the Yoruba onile gogoro or akaba hairstyle rises above its wearer’s head on slender columns. Named after ladders and the skyscrapers taking shape in Nigeria, its twists form a floating circlet high in the air.”

A hairstyle mimicking the city skyline would seem radical in any western setting today; Afrrican Artists demonstrates just how pioneering and assertive postcolonial African culture was, over forty years ago. To see many more images like this, order a copy of African Artists from 1882 to Now here.