Deanna Petherbridge - Why I Draw

This Vitamin D3-featured artist uses pen, ink and her internal moral compass to create her detailed images of urban landscapes characterized by vertiginous perspective and dramatic shifts in scale

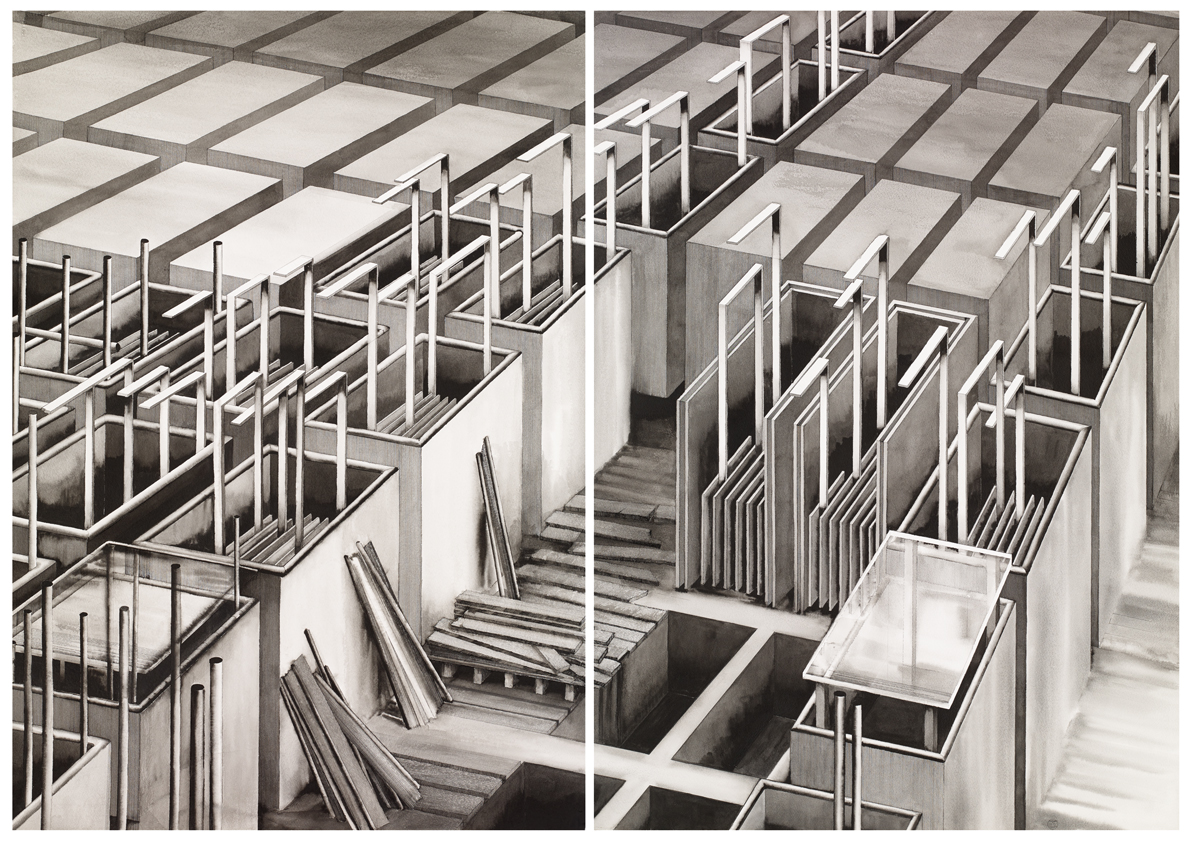

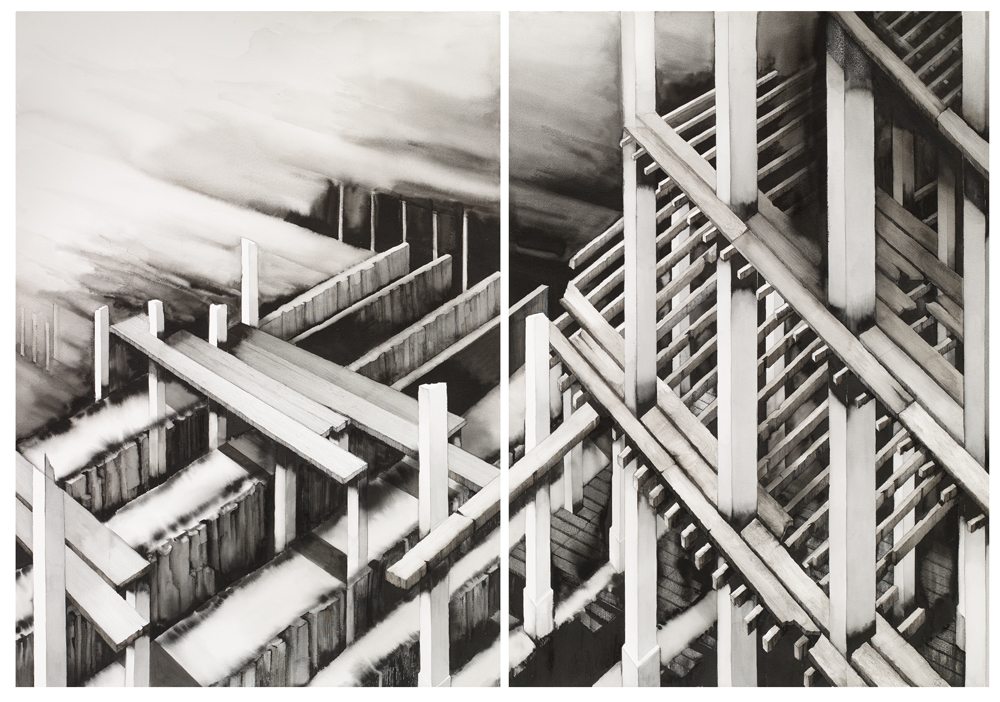

Working almost exclusively in monochromatic pen and ink, Deanna Petherbridge has dedicated herself to drawing for over fifty years. Her work conflates bold geometries with the imagery of pistons and machines, merging industrial and architectural motifs. More recent large-format pieces feature urban landscapes characterized by vertiginous perspective and dramatic shifts in scale. Everything is untethered from gravity as objects float freely amid constant spatial and perspectival contradictions.

Petherbridge’s vision of the metropolis is mediated through the prism of her imagination, the drawings inspired by her extensive travels, and sometimes online imagery.

We are reminded of the ubiquity of cranes and building sites in urban spaces and cities unwillingly reshaped by conflict. Wars, natural disasters and economic impulses each shape the city in different ways, leaving behind psychic and physical scars.

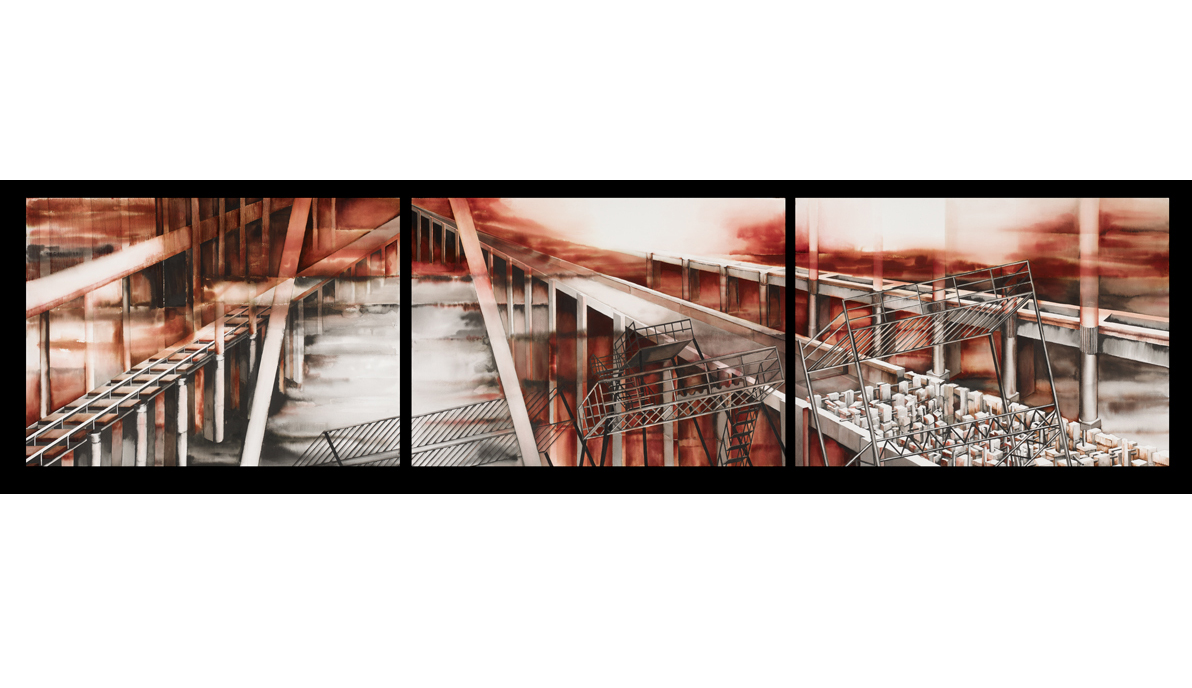

In the triptych Blood Crossings, 2019, a very long drawing of three horizontal panels, Petherbridge used railway lines, bridges and roads as structural metaphors of movement and travel to suggest the bleak perspectives of forced migration across continents.

Her graphic response to the pandemic is ongoing, but in the first of the series, Camp Covid, 2020, she reflected on the restraints and restrictions that it has wrought across the world, in a landscape of shuttered tombs and graves and superimposed regimentation. The View from Hotel Pandemia, 2020, offers, instead, skeletal ruins and a fragmented infrastructure.

These are tangled drawings that invoke the speed in which urban spaces are made and unmade. Yet, for all their evocation of velocity, Petherbridge asks us to slow down and pay attention to the role of images. She makes drawings with cinematic ambition, situating the discipline alongside filmmaking, music and literature as a cultural form capable of articulating the crises that pervade our current moment.

Petherbridge is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, our new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We sat her down and asked her a few questions about how, why and when she draws.

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I'm Deanna Petherbridge, a drawer and writer, and the state of the world is very much on my mind. This is what I have been drawing this year, mainly in pen and ink on paper diptychs, and possibly will be doing in 2021 as well. When I refer to 'the state of the world' I don't only mean Covid 19 and the impact of this pandemic, but also global warming and the destruction of the environment that is reaching apocalyptic levels, while wars and bad governments proliferate and add to the sum of human suffering in our interconnected firmament. I am old enough to care passionately, and while I welcome the hopeful activism, positive stance or occasional detachment of so many young people, I also believe that dealing with these issues through visual imagery is the very function of being an artist ... even if what we make isn't all irony or good cheer and false bonhomie. This is the profoundly serious subject-matter today: how can we avoid it?

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? I have always been a drawer, celebrating the accessibility and economy of lines and marks made by simple and ubiquitous tools such as pens and pencils, which drawing shares with writing. It has been my sole and major medium since the 1960s. Over the years, I have taught drawing, endlessly talked about it to students in lectures and presentations; written about it in books and articles and promoted its validity for the general public in curated exhibitions and in the media. So, for me it hasn't only been a special relationship but the defining relationship of most of my artistic life.

In my drawings, I employ architectonic and mechanical imagery and compositional means as metaphors of the human condition: representations of transparency, shafts of lights, moving lines and evolving shapes, the white of the paper support as both surface and depth are contrasted with drowning shadows or mocking and contradictory references to destruction, fragmentation and decay or to landscape and place. The imagery moves between abstraction and referential hints of material or dream worlds and most works are given titles because they are about ideas and visual narratives.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? Although every generation claims a sudden renewed interest in drawing, I believe it has never completely fallen into desuetude: just followed new paths, media or critical assessment ... if occasionally denial. My promotion of drawing was probably most fervently pursued and high profile when I was Professor of Drawing at the Royal College of Art from 1995 to 2001, but different arguments and strategies have been necessary as the cultural world has morphed over time from modernism and abstraction to post modernism or whatever we designate it today. In the 1980s, for example, when I was teaching at the Architectural Association and the polytechnic departments that preceded university art courses, the significant matter was to welcome back drawing as a legitimate practice.

This was after its banishment from British art curricula in the 1970s and the need to establish convincing narratives about drawing from the human model in line with feminist, queer and post-colonial studies, issues of personal subjectivity and incipient conceptual art. More recently, as drawing has evolved into performative practice, as a public and participatory bodily activity, there has been a need to reshape a countervailing argument of drawing as the rigorous means of formal analysis and exploration of ideas and affects that underpins all private as well as communal visual practice.

And in the times when philosophical or theoretical ideas have swamped visual histories and art critique for students and teachers alike, I have seen the need to reinforce those potent underlying issues of making, materiality and hand-and-eye skills that drawing exemplifies. An understanding of drawing-as-making allows us a confident path to understanding past art as much as appreciating current practice, and this was the kernel of my book The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice, 2010 where I attempted to analyse processes and explain how, why and wherefore people think and draw.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Looking back on a lifelong involvement with pen and ink drawing, I now realise that what I do challenges easy assumptions about drawing as much as it represents an evolving personal oeuvre. My drawings are very elaborate, very complex and very finished, thereby challenging the majority view of art critics and teachers that drawing should be spontaneous, gestural, unfinished and sketch-like. They fly in the face of the universal (or is it just British?) distaste for anything hand-drawn that is precisely defined as somehow wickedly 'meticulous' and repressive, whereas digital media are never subjected to a similar critique. And, my explorations of pictorial depth and contradictory 'perspectives' and spatiality challenge the stale ideology of unquestioningly honouring the frontal picture plane of modernity in drawing and painting alike.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? I have recently written about the amazing Australian artist Joy Hester (1920-1960) whose drawings were done publicly on torn and disposable scraps of paper, while sitting on the floor or in nature with friends, as a deliberate expression of the democracy and accessibility of drawing as witness to everyday life. And I have so often seen that drawing is the only means to hand of those in poor countries or in oppressive conditions, where expensive media are the tools of controlling institutions and hegemonies or gestures of gallery profligacy . This background (I was born and grew up in South Africa) supplies me with the confidence that pen-and-ink lines are the key means for challenging large themes and complex ideas as well as modest gestures: doing much with little. I draw most days, except when writing about drawing, and it has always given me pleasure to work in places other than my studio, travelling light with a roll of paper and a bottle of ink - plus a straight edge for moral compass!

You can find out more about Petherbridge's work at JSVCprojects, and see more images on her website. Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola Christina Quarles, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Emma Talbot is available now. We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.