Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings - Why We Draw

What's the one thing these Vitamin D3 artists can't get enough of? Each other. But exercise, travel and dedication also help them create their art

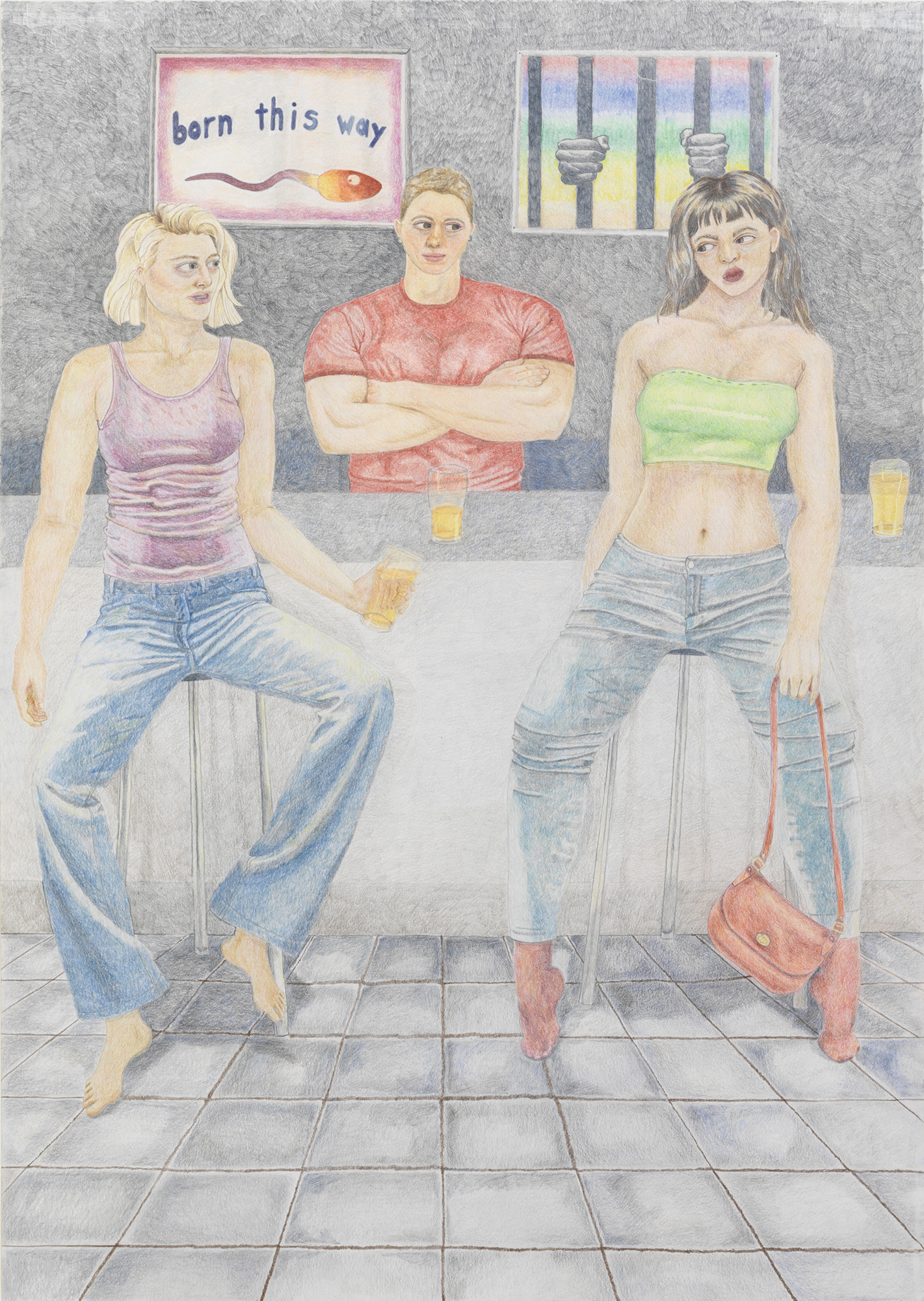

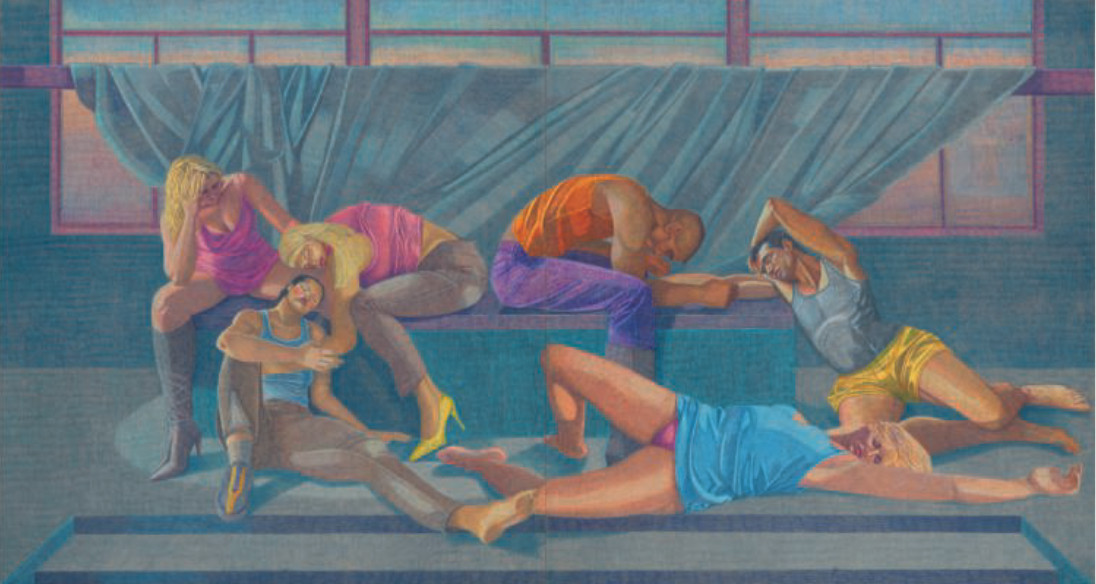

While their style winks at the stylized, highly masculinized homoerotic art of Tom of Finland, the majesty of how artist duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings use rhetoric and storytelling in their scenes recalls the Renaissance Masters. Inspired by a trip to the Vatican, such influences are evident in the large-scale drawing Funny Girls (2019). Groups of statuesque people gather amid the grand architecture of a sex club, merging risk and pleasure. In the left-hand corner, two people kneel before a woman while others watch. The reclining pose of a man next to a pointed finger recalls Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – God, here, a woman – while the perfect perspective of arched windows and domed doorways suggest Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509–11), which depicts the formation of knowledge, with Plato and Aristotle conversing. For Quinlan and Hastings, such scenes should be mined for cultural, social and political purposes, proposing new power structures and, ultimately, strategies of inclusivity.

Their graphite, pencil on paper drawings are about not only the social space of queer life but also the gendered nature of urban architecture and public space. They pose the questions: who is allowed where, and when.

The artist duo described the questions that preoccupy them in a 2020 interview with Queer Direct: ‘Who is able to take risks? Who is allowed agency over their own pleasure? How to be visible without being exploited? How to lay claim to public space?’ Initially investigating male sex culture in the UK, demonstrated by their moving image work UK Gay Bar Directory (UKGBD) (2016), which responded to the systematic closure of LGBTQ+ social spaces, Quinlan and Hastings consider the political impact of behaviour patterns. They use the idea of the spectrum of male power – as demonstrated in sex clubs – as a metaphor for how power manifests in other spaces, not least the boardroom, and how this might be redistributed.

Quinlan and Hastings are among over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, Phaidon’s new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We sat them down and asked them a few questions about how, why and when they draw.

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? We are actively trying to empty our minds and not think or feel anything. Over the last year we poured too much of ourselves into our work and entered a state of creative deficit and mental fatigue. We worked when we were sick, we worked when we were tired, we worked when the whole world was falling to pieces. It's almost as hard to be empty as it is to be full, you have to dispose of your routine and abandon your coping strategies.

At first there is a profound sense of alienation - your life has changed but you have all the same concerns and anxieties. We approached our break in the same way we approach our deadlines, rushing, planning and filling up time we continued to exhaust ourselves physically and mentally. Eventually these concerns and anxieties slipped away and we achieved synchronicity with the world around us. At this point we normally start filling the empty with fertilizer - travel, friends, exercise, exhibitions - everything becomes a possible revelation. In this moment of global and national crisis it's hard not to fill the empty with anger, disappointment and fear. The one thing we can never get enough of is each other, we are never apart but when we work we feel lonely and we miss each other, the work exists between us. In our break we feast on one another, that's one thing the pandemic has not changed. When we probe ourselves as artists, we find bruises; it's not yet time to start thinking again.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? We have both drawn since childhood but it didn't enter our practice until relatively recently in 2017. Our first drawing show was called Fuck Me On the Middle Walk at Truth and Consequences, a commercial gallery in Geneva that has since closed. We made the drawings after filming the UK Gay Bar Directory (2016) a moving image archive of gay bars in the UK. To film the directory we spent nine months travelling around various cities and gay villages inserting ourselves into different communities and building our research, it was a difficult and overwhelming experience. Drawing felt antidotal; a way of working that was private and intimate. We were living in a one-room apartment and we drew on the bed, we barely left our room the whole winter we spent working on the show. Our first drawings were playful and experimental, we followed no rules except the ones we made for ourselves and we argued about absolutely everything as our two styles clashed on the page. To our joy people responded well to our drawings and we entered a rigorous phase of drawing training, we felt like apprentices in a renaissance masters studio and we approached every drawing as a stage in our training. Now our drawing is incredibly regimented, through our training we have finally achieved symbiosis in our drawing styles and we no longer need to argue, we are one hand. We would like to learn to incorporate the early freedom and playfulness that we experienced back into our drawing but we are not quite there yet in our apprenticeship to one another, for us this is when we graduate from drawing apprentice to drawing master.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? We try not to involve ourselves too deeply in the coming or going of trends as it is a gateway to insecurity, self-doubt and bad art. We have found that the public respond well to our drawings and that is enough for us.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? The hardest thing to get ‘right’ is the psychological dimension of drawing; everything else can be achieved in a pragmatic and straightforward way, even talent. The right attitude to drawing is to understand the steps that the image requires you to complete and to follow these steps in an organised and fearless manner. The wrong approach to drawing is to become emotionally involved with the pencil, when this happens you lose perspective and it's inevitable that you become completely hysterical and unable to perform basic tasks.

Every drawing has peaks and troughs sometimes you can only achieve the correct approach to drawing by first exhausting your emotional involvement in a multiple-breakdown spiral. When you achieve the correct attitude to drawing you can make more progress in one hour than two weeks of fear-saturated work. When we both get the drawing fear at the same time the studio becomes a hostile almost unbearable place to be, when we lose our fear we float on a cloud of drawing logic that is blissful and self-perpetuating.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Our drawings are not direct or immediate to produce; they are born out of many hours of hard physical work. We are both naturally drawn to works that are challenging, masochistically so, for us this is the appeal of drawing.__

__

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something most of us cannot? Even when we were children we drew seriously as if we were artists and we experienced the same fears and joys, for us drawing was never innocent. When we were children we both felt shame and anger when we drew as we did not possess the necessary skills to translate the images in our heads or the world around us onto paper. We would feel sick, cry and scrunch our inadequate works up, sometimes we still experience this. Now it is our privilege to dedicate more time and resources to drawing, it is our job. Occasionally we surpass even the images we imagine in our heads, it's heavenly.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? The physical place is interesting. Our exercise regime is very important to our drawing practice somehow. Making a drawing requires strength, perseverance and discipline - traits that are transferable from running, strength training and weight lifting. Often when working on a project we begin with an integrated workout routine, as we get deeper into the project the workouts stop and are replaced by longer hours in the studio. Drawing is near sedentary, we tend to sit or stand in a fixed position but we finish the day exhausted with cramps all over our body, the focus of drawing is as physical as a workout. It's important to go into a new drawing strong and mobile, the drawing then wrecks us and the cycle repeats itself.

Geography is also important, it is our privilege as artists to work in many different places. When working on a particularly long or difficult project we like to uproot ourselves and rent a studio somewhere new. The isolation of a new place is the ideal condition to create work in. In a new city you shrug off your home responsibilities and your ties to other people which allows you to build a new routine centered around work.

We prefer a monastic lifestyle when we are working hard, a life whittled down to the essential elements of work, food, exercise and sleep. Often our ideal work conditions make us very lonely and alienated but these feelings have somehow become important in our drawing practice. We often feel that we live our lives in chunks that are entirely separate, each one defined by a different project or artwork. This feeling is intensified because we work in so many various disciplines, we draw and paint frescoes but we also make films. Making films requires the opposite conditions to drawing, you're dependent on your team and your network, the monastic lifestyle goes out the window and every day is unpredictable. Cycling between the two work conditions is like an engine in our practice, it motivates us endlessly.

You can see more of Hannah Quinlan's and Rosie Hastings' work via their Instagrams (Rosie is here; Hannah is here); their galleries Bortolozzi and Arcadia Missa. Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Emma Talbot is available now at in our store. We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.