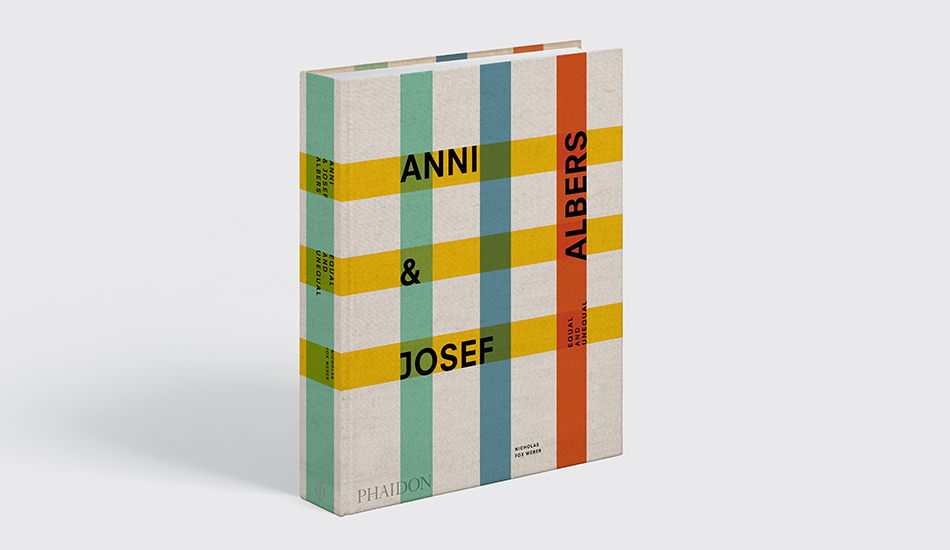

The square paintings that established Anni and Josef Albers

Anni & Josef Albers, examines how a series of repetitive paintings went from object of ridicule to high society status symbol

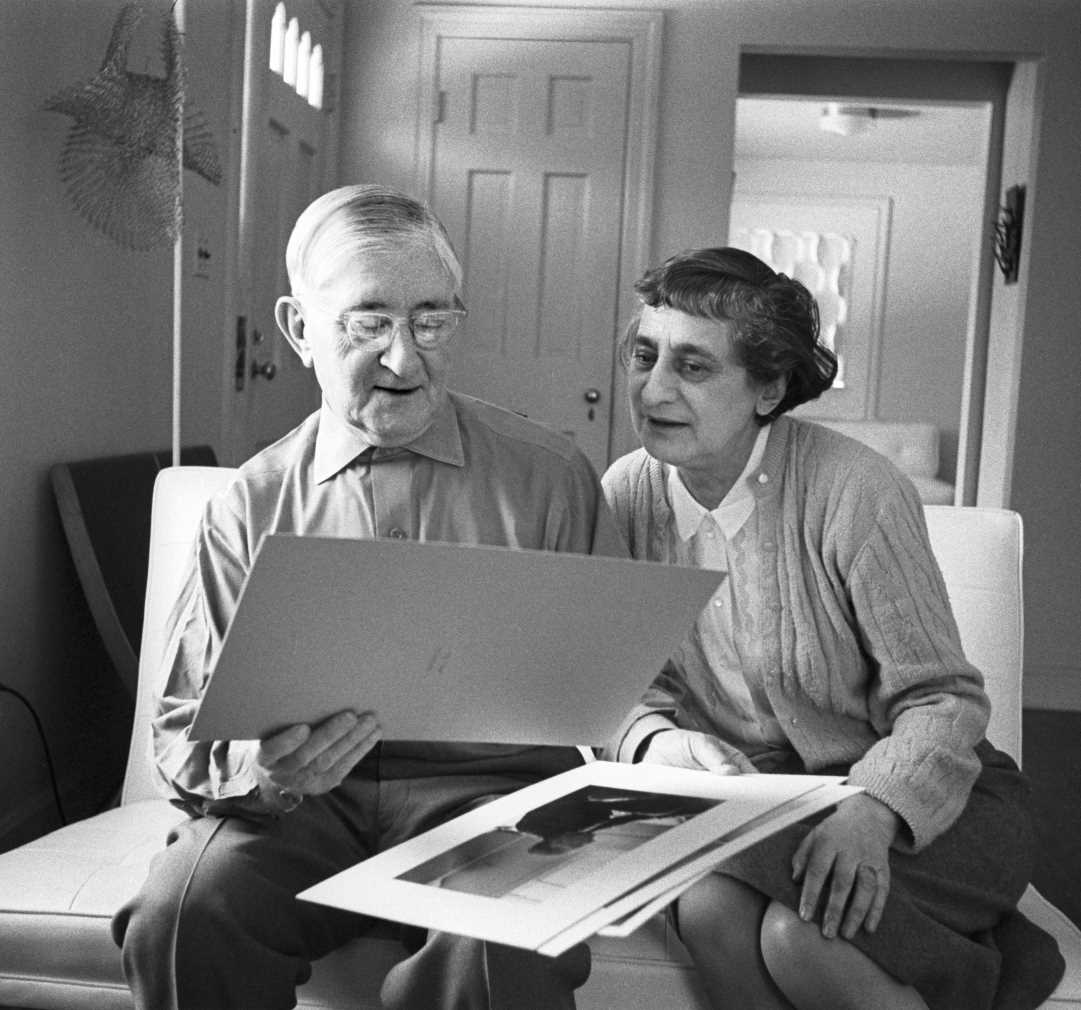

Our new book Anni & Josef Albers takes its subtitle, Equal and Unequal, from a painting - just one of five works - that hung in the influential artist couple’s final home, in New Haven, Connecticut. Which other canvases did this deeply ascetic, though deeply aesthetic couple, deem worthy of their dwelling? Four different versions of Homages to the Square, Josef Albers’ most famous series, which the artist and educator began working on in 1950.

The book's author, Nicholas Fox Weber, establishes some precedents for these vital, abstract works of concentric squares that established Josef and his wife as art world stars. There are Josef’s early, impressionistic still-lifes reproduced in our new book that look quite a bit like this later series. There are aspects of the couple’s fascination with Pre-Columbian art that clearly figure in this repetitive production of similar looking pieces; as does the couple’s reverence for logic and numbers. Anni and Josef’s choice not to have children is partly accounted for with Josef’s remark that his smaller Homage works, painted later in life, were his “children.” Even Josef’s father, a painter decorator figures in the story. “His father had told him, ‘When you paint a door, you work your way from the middle out; that way you catch the drips and don’t get your cuffs dirty,’” explains Fox Weber. “Josef always painted the middle square first and from there worked his way out meticulously.”

Though the book, of course, offers a much more lucid account of these square works, upon which the couple—who shared so much in terms of artistic outlook—built their later life. “From the start, he made rules for the Homages that he stuck to rigorously,” explains Fox Weber.

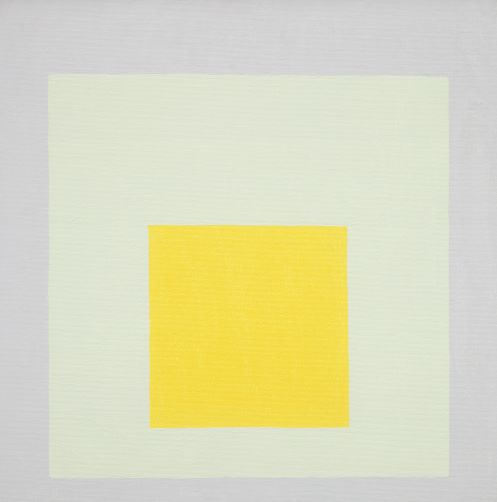

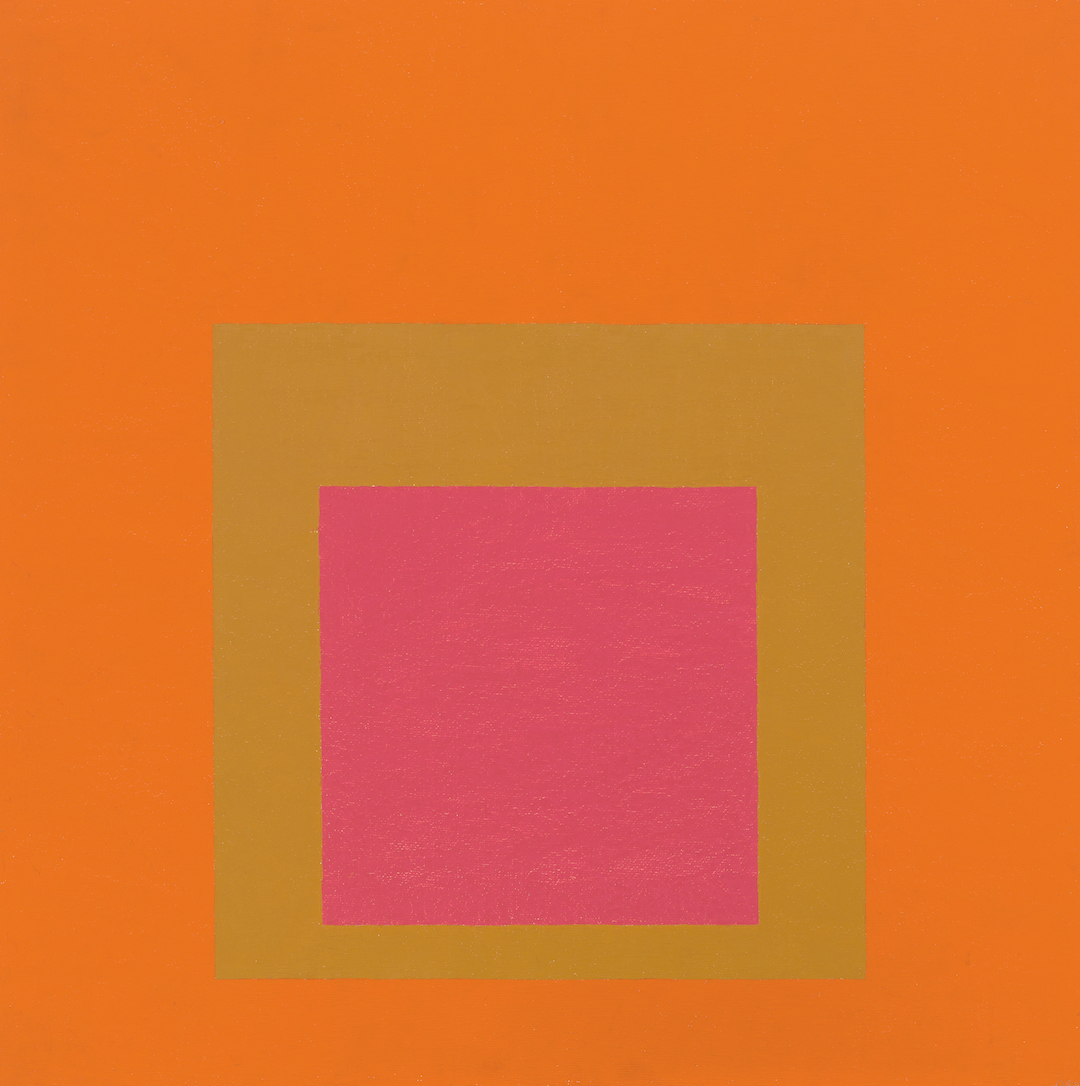

“Each artwork consisted of squares nested within one another. The proportional relationships with which they were positioned required that the distances—the width of the outer squares—to the left and right of the central square were precisely double the measurement of the amount of outer squares visible beneath the one in the middle. The top dimensions were, also with unwavering exactitude, three times those at the bottom. Sometimes there were three squares, sometimes four. The ones with four squares all have the identical layout. There are three variations of the ones with three squares. If one considers the Homages as ten units across and ten high, in two of those arrangements, the middle square is four units wide and high, and the second square—as you move outward from the center—is either six units wide (with a single unit of color visible underneath the middle square, and one and a half units above the middle square) or eight units wide (with one unit visible underneath the middle square and three above it). The third three-square version has a middle square that is six by six units, with, in the second square out from it, half a unit showing underneath and one and a half above. The one-two-three ratio was inviolable. Josef depended on it to induce tension and to produce a variety of effects.

“The formula, like that of haiku or a sonnet, provided a welcome discipline that in turn allowed a range of differences in plastic movement,” the author goes on. “What varied infinitely were the colors. The name Homages to the Square had a very Albersian playfulness; the series could equally well have been called Homages to Color, were that not far too obvious for Josef. He applied thousands of colors, straight from the tube, delighting in the difference between a Winsor & Newton Burnt Sienna and a Grumbacher Burnt Sienna, experimenting with ten different manufacturers’ Mars Yellow, because of his cognizance that each was different.”

Despite Josef’s earnestness, not everyone could take the Squares seriously, at least to begin with. “Even Anni—at least so she claimed, with her usual predilection to present a person’s weakness, the person often being herself—said to him in fright, ‘My God! Now you’re painting Easter eggs. We will never have enough to live on.’”

However, over time the art world did begin to appreciate Albers work, and pay high prices for the squares. “By the mid-1960s, each of these works, which could be bought for a song early on—if anyone was bold enough to purchase one—was fetching large amounts of money in fancy international art galleries or auction houses,” writes Fox Weber. “A cartoon in the New Yorker magazine showed a well-heeled couple leaving a cocktail party in what is clearly a fashionable New York apartment saying, ‘Bach cantatas, Barcelona chairs, Albers prints, quiche—why do our new people always turn out to be like our old people?’”

With the money they now able to collect art themselves more ambitiously, while the Squares themselves made their way into quite a number of prestigious homes. Josef’s final painting was a work in this series, and, a little over 42 years after his death, in March 1976, two from the series found their way into the most prestigious address in the land.

“Shortly after Barack Obama was elected president of the United States in 2008, he and his wife, Michelle, selected art they wanted to borrow from the Smithsonian to hang in the White House,” write Fox Weber. “ This was a well-established tradition, but the Obamas’ taste was not traditional. Among other things, they chose, at the Hirshhorn Museum, two of Josef’s Homages to hang in the family dining room. Michelle Obama would later say that ‘we simply love looking at those Albers paintings during dinner.’”

Perhaps Michelle and Barack saw the same beauty that Anni and Josef admired in their own home, decades earlier. For more on this serious, as well as a great deal more on these important artists, order a copy of Anni & Josef Albers here.