The folk art that changed Anni and Josef Albers

Our book Anni & Josef Albers includes an examination of the couple’s love of pre-Columbian art and its influence on them

Anni and Josef Albers weren’t entirely sure where they were going when they crossed the Atlantic to take up teaching positions at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

Our new book Anni & Josef Albers chronicles the couple’s incredible career, from the Bauhaus to the most exulted circles in modernist art. The text, by Nicholas Fox Weber, the long-standing executive director of the Albers Foundation, is a finely crafted art-history document and a richly engrossing diptych-like biography, filled, as it is, with both personal recollections and meticulous research.

However, as Fox Weber points out, the couple did know one thing back in 1933, when they left Nazi-occupied Europe for America: the crossing would bring them closer to an indigenous art scene they both admired.

“They realized that they would be not too far from Mexico, where much of the art they both adored in Berlin’s Ethnologisches Museum had been made centuries earlier. The Alberses relished the idea of being nearer to the achievements of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca cultures that had come to fascinate them.”

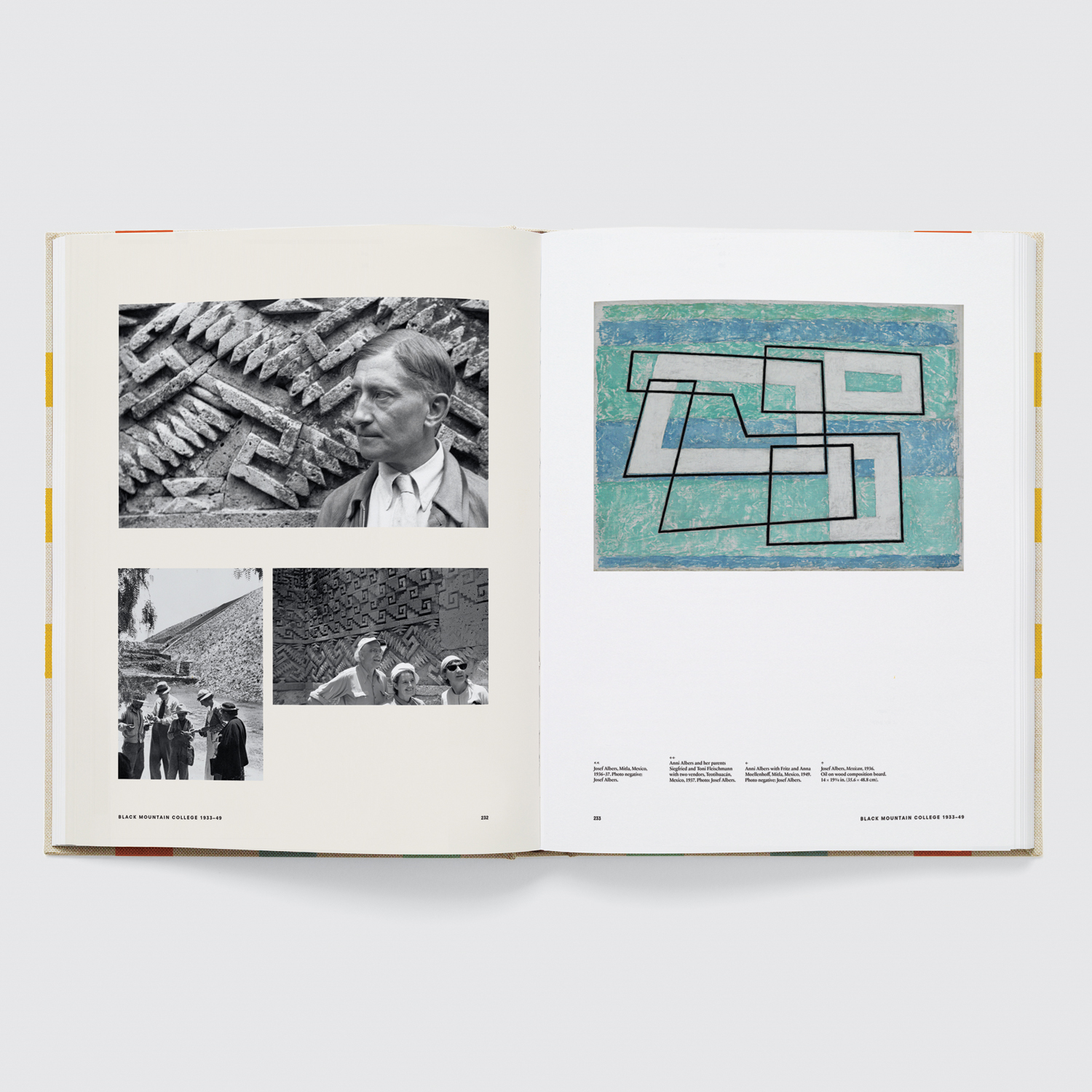

Over the following years they took many trips south of the border to see the works they so loved, and collect quite a few examples. Here’s how Fox Weber describes their earliest expedition.

“In 1935, on their first trip to Mexico, Anni and Josef and [Black Mountain staff] Ted and Bobbie Dreier, in the Dreiers’ second-hand Ford Model A convertible, first headed south-west to Texas. They then picked up the single road that went south from Texas to Laredo, Mexico, and, from there, to Mexico City and Oaxaca.

“They stopped wherever anything attracted their interest. In one village, Anni, physically less robust than the other three, waited in the car while Josef and the Dreiers walked to a nearby church to explore its interior. A little boy approached her and asked if she wanted to buy the baby goat under his arm. She said, in the kindest way, that she was afraid she would not be able to travel with the goat but after added, only half facetiously, that if he were offering the blanket in which the creature was wrapped, she would be interested.

“The child replied by telling her he also had a small figurine wrapped in a handkerchief. ‘I couldn’t imagine that there was anything like that piece still available, but it cost only a few pesos, and so I bought it,’ Anni would later recall.

“The Alberses barely had sufficient money to buy street food for lunch, but she could not resist the tiny ceramic figure, some three inches (eight centimeters) high, of a woman with an elaborate headdress, oversized head, slanted eyes, simplified nose and lips, large earrings, exaggerated breasts, squat arms, and tapered legs,” Fox Weber goes on. “It was unlike anything Anni had ever seen before, except for the few objects that had grabbed her and Josef ’s attention in Berlin’s Museum of Ethnology, but she was riveted by the bold simplicity that many people considered unacceptably primitive or child-like. Shortly thereafter, she and Josef went to see the noted archaeologist George C. Vaillant, who told her that she had acquired ‘a treasure’.”

While the beauty of these works are eternal, Anni and Josef’s understanding of and appreciation for pre-Columbian art was very much a product of the attitudes of their age.

“The Alberses both had this idea of uneducated, unsophisticated cultures as embodying what was best in humanity,” explains the author. “It could be the students Josef had when he taught at what was called a ‘peasant school.’ It could be the people of Mayan descent Anni sat with on buses in Mexico City. They functioned easily in sophisticated milieus, but saw situations where people were their most natural and least cultivated as being a form of ideal.”

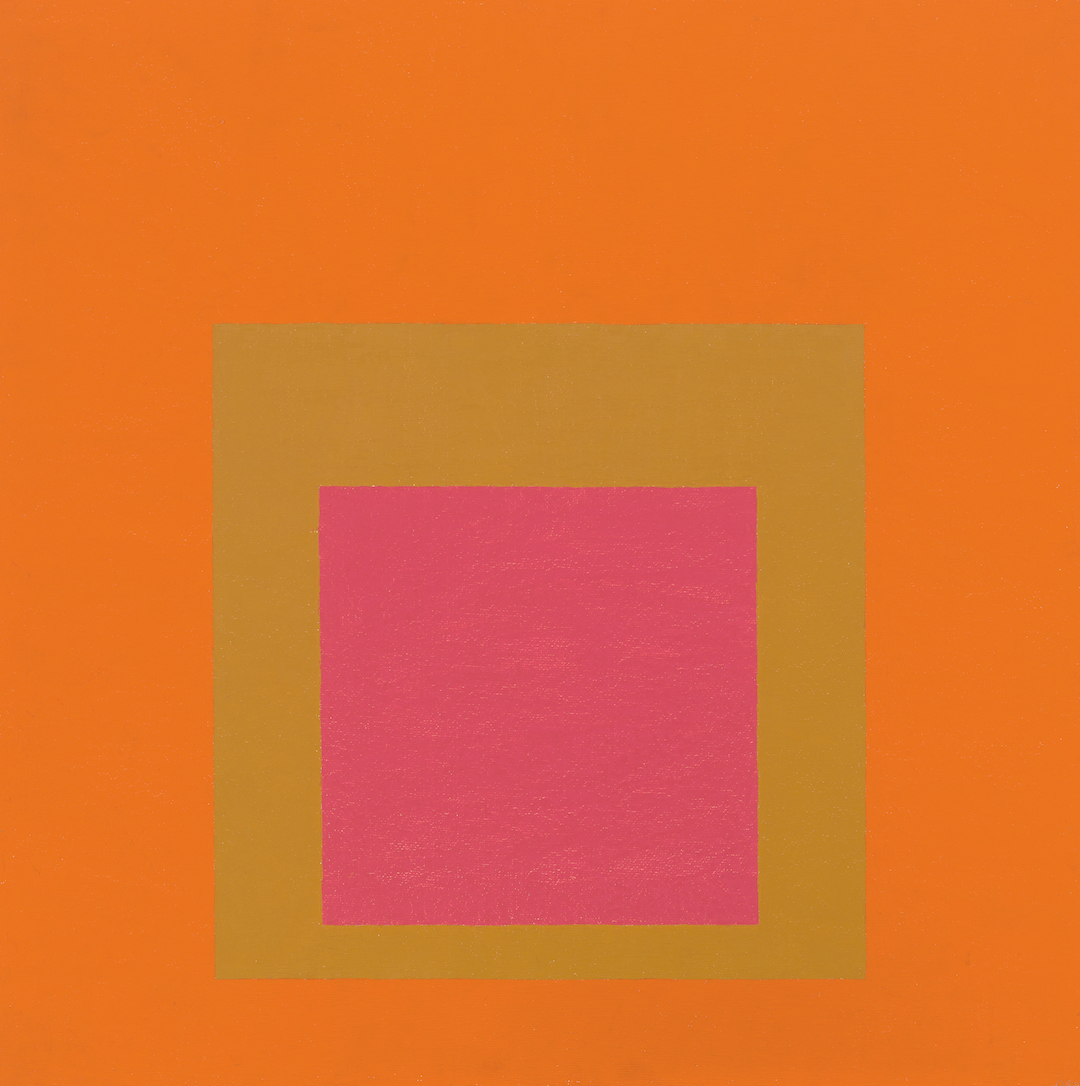

While the couple never mimicked the art they bought, their ever-growing collection informed their own work as Fox Weber explains. “Over time, Anni and Josef acquired around a thousand pre-Columbian objects, from all the major cultures. Josef had a particular passion for small ceramic Chupícuaro figurines, from the period of 400 to 100 BCE, and relished their sameness as well as the subtle variations within the perimeters of their all being about the same size (around 2.2 inches [5.5 centimeters] long), and formed so similarly that is often hard to tell one from the other.

“In many ways, his Homage to the Square series resembled those tiny goddesses in the way that their uniformity caused viewers to notice their slight differences and appreciate the uniqueness of each all the more astutely,” Fox Weber goes on. “But Anni and Josef were united in their taste and their passion for a range of vessels, figurines, statuettes, and jewelry from the Tlatilco culture, which flourished from 1200 to 800 BCE, as well as pieces in the Nayarit, Colima, and Guerrero styles; objects found in the areas of Teotihuacán, Monte Albán, and Veracruz; Aztec pieces from the fifteenth century; and modest but captivating objects of contemporary Mexican folk art.”

To see examples from this collection as well as many, many works by the artists themselves, order a copy of Anni & Josef Albers here.