How Philip Johnson and America saved Anni and Josef Albers

Our new book describes how a chance meeting in the street and the invention of Black Mountain College helped the couple escape Nazi Germany

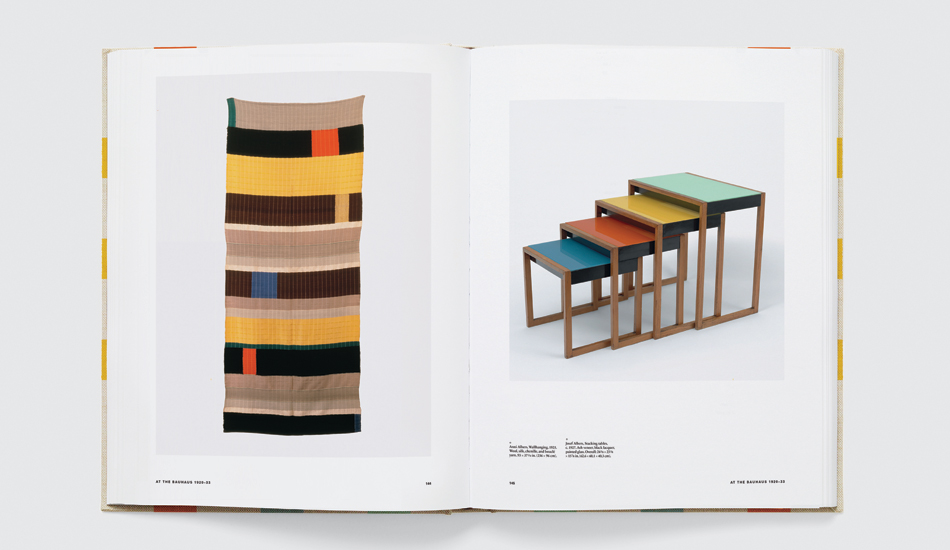

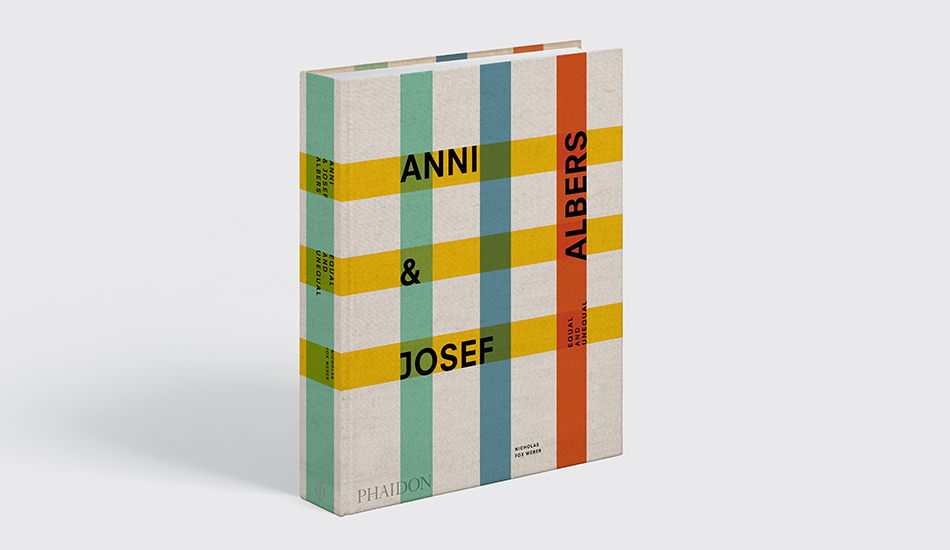

For many art lovers, Anni and Josef Albers will forever be associated with Germany and that seminal German art school, the Bauhaus. Indeed, our new book Anni & Josef Albers chronicles the couple’s decade-long involvement with the place.

The text, by Nicholas Fox Weber, the long-standing executive director of the Albers Foundation, is a brilliant art-history document and an engrossing diptych-like biography, filled, as it is, with both personal recollections and meticulous research.

In these pages we learn about Anni and Josef’s formative, though very different experiences at the Bauhaus, as both students and teachers. However, Fox Weber also describes the tragic turn of events that led to the school’s closure, and the couple’s subsequent emigration from Europe.

The transition from one school to another was not an easy one. “The Dessau government effectively closed the Bauhaus in 1932 by declaring that it would no longer pay faculty salaries,” explains Fox Weber; though the Nazis didn’t physically shutter the school, the regime did cut off funds after the faculty refused to support the party’s politics.

“The institution in which Anni and Josef Albers had enjoyed a wonderful new way of life and had taken art and design to new summits, was to become history,” writes Fox Weber.

Fox Weber suggests that Anni blamed herself for the couple having to leave Germany; after all, she was Jewish, while Josef was German. However, the author also explains that it was Anni, not Josef who cultivated the connection that led to them crossing the Atlantic so successfully.

“One day during that fraught April when uniformed Nazis barred Mies’s entrance into the Bauhaus, Mies’s greatest admirer, the young American architect Philip Johnson, who was in Berlin, ran into Anni by chance as they were walking toward one another on a sidewalk in the center of the city,” writes Fox Weber.

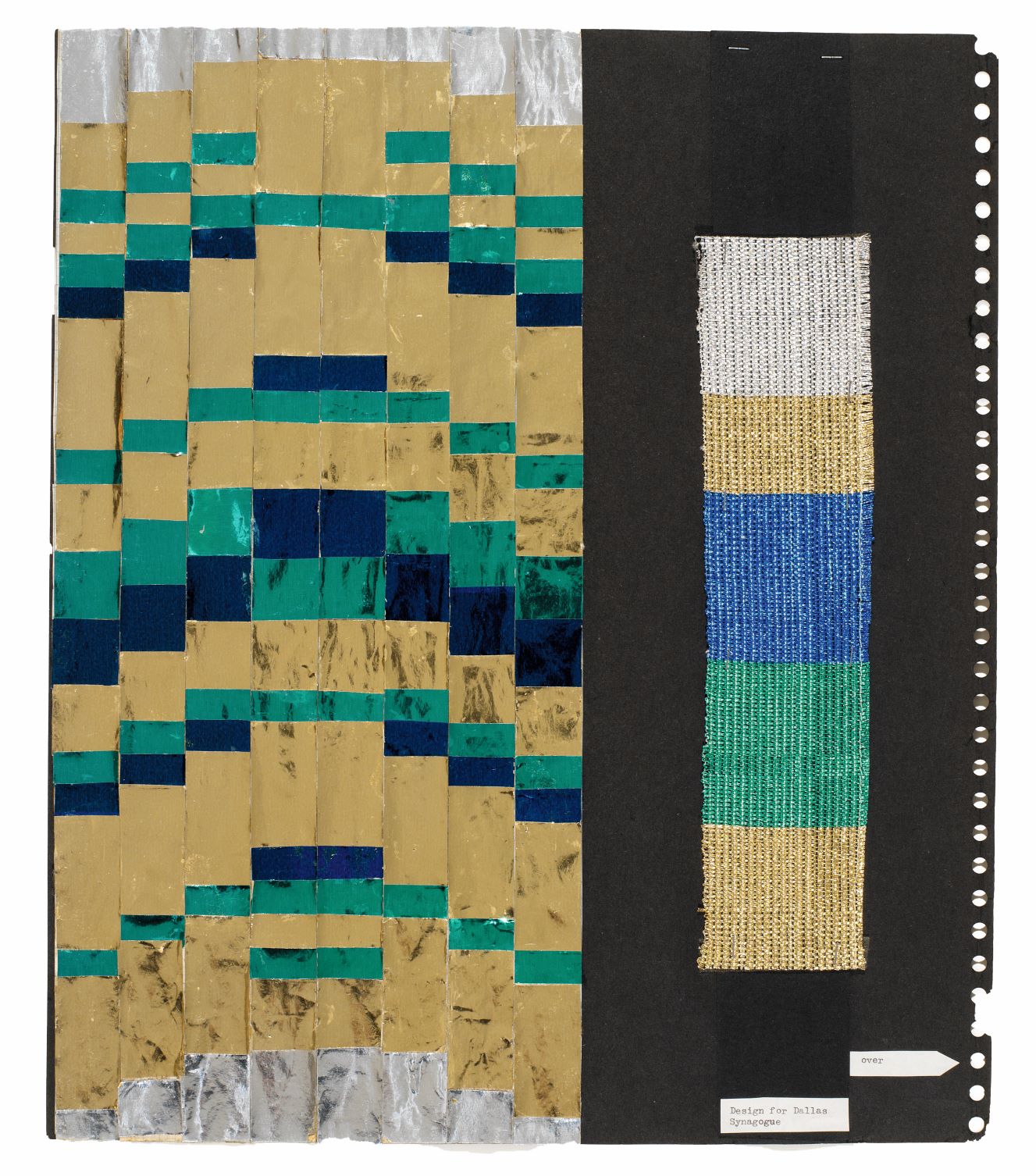

“Johnson was happy to see her; they had met at the Bauhaus Dessau, which he had visited in the late 1920s. It had been at Johnson’s behest that the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art put on a Bauhaus exhibition in 1931 in its two rented rooms over the Harvard Coop in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This presentation of art and objects recently made in Dessau was the first exclusively Bauhaus show in America. Johnson was particularly taken with the textiles produced at the Bauhaus and considered Anni one of the top designers.

“Anni was proud of the white linoleum floors she had just installed in her and Josef’s apartment and had an instinct that Johnson would like them too. The apartment was nearby, and she asked him to come up for tea. As soon as he walked in, Johnson commented on a textile sample he thought to be by Lilly Reich. Anni explained that it was in fact by her; Johnson was puzzled that Reich, whom he knew quite well through Mies, had credited herself for it. Besides, he found Anni highly original and courageous, exceptionally so.”

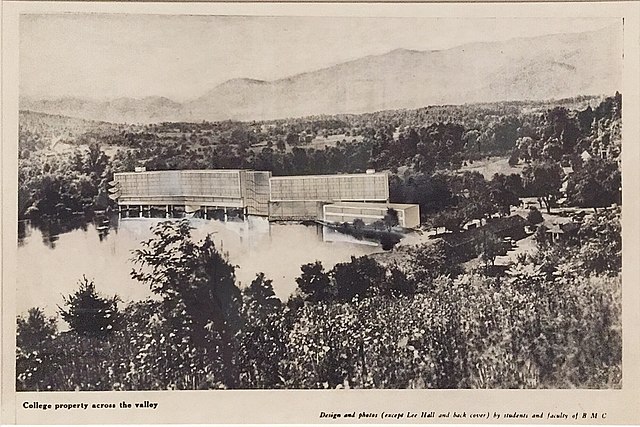

Upon his return to the US, Johnson, came across an opening he felt would suit the couple. “It was a small, progressive institution in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, and its three founders wanted a head teacher who could make visual art the fulcrum of the curriculum,” writes Fox Weber. Josef was offered the key position, while Anni was given a weaving job.

“When the Alberses received a telegram asking if Josef was interested in the new position, he and Anni cabled back that he spoke no English. Anni, who had had an Irish governess, did speak and read it a bit; Josef did not,” the author explains. “Johnson cabled back, ‘Come, anyway.’ Anni said that they sat side by side on their bed, their ‘feet dangling,’ as they considered the prospect. They had no idea, meanwhile, where North Carolina was. ‘At first, we thought it might be in the Philippines,’ said Anni.”

Though their geography was a little off, the change was equally stark. The couple arrived in November 1933, sailing to America on the SS Europa, and were amazed by the luxury and modernity they came across in New York City.

The school, in the hilly woodlands of North Carolina, was also filled with surprises. “One of the first things Anni noticed was an information bulletin tacked onto a white column of the college’s main building, Robert E. Lee Hall,” writes Fox Weber. “She could not imagine how it was possible to penetrate marble with a small brass nail. She got close to study this remarkable phenomenon, only to discover that, in America, white Ionic columns were made out of wood that had been coated in paint. This signified a great deal to Anni: the extent of difference between America and Europe, the lack of dependence on expensive materials in order to convey importance, and a certain ingenuity. She was in an entirely different world, and as soon as she took up weaving again, her work reflected the earthiness and informality that surrounded her. Sharp edges gave way to muted ones, smoothness to texture, rigidity to relaxation.”

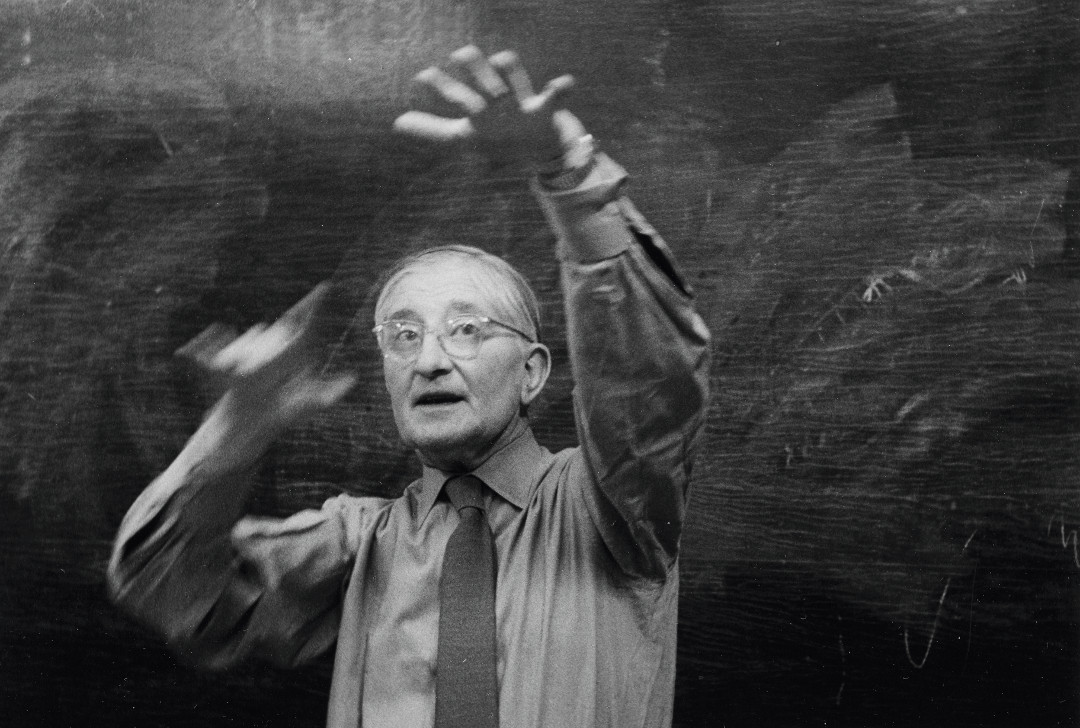

Josef too felt inspired. Fox Weber describes how in his paintings, he used “oil pigments as never before, evoking the local landscape and the pleasures of everyday life in rural North Carolina in a way he had not even remotely envisioned two years previously. A joyful sense of abandon infused his art.”

Though Anni was pretty good at English, the language held Josef back to some extent. “As [wife of the college co-founder] Bobbie Dreier recalled, from the start Josef made his primary goal crystal clear when he said it was, ‘To make open the eyes’; shortly afterward, he fine-tuned his English to declare, ‘I want to open eyes.’”

During their time in North Carolina, the couple also took opportunities to travel, heading to Florida, Cuba and Mexico. However, this exposure to new environments and cultures didn’t greatly change their artistic practices.

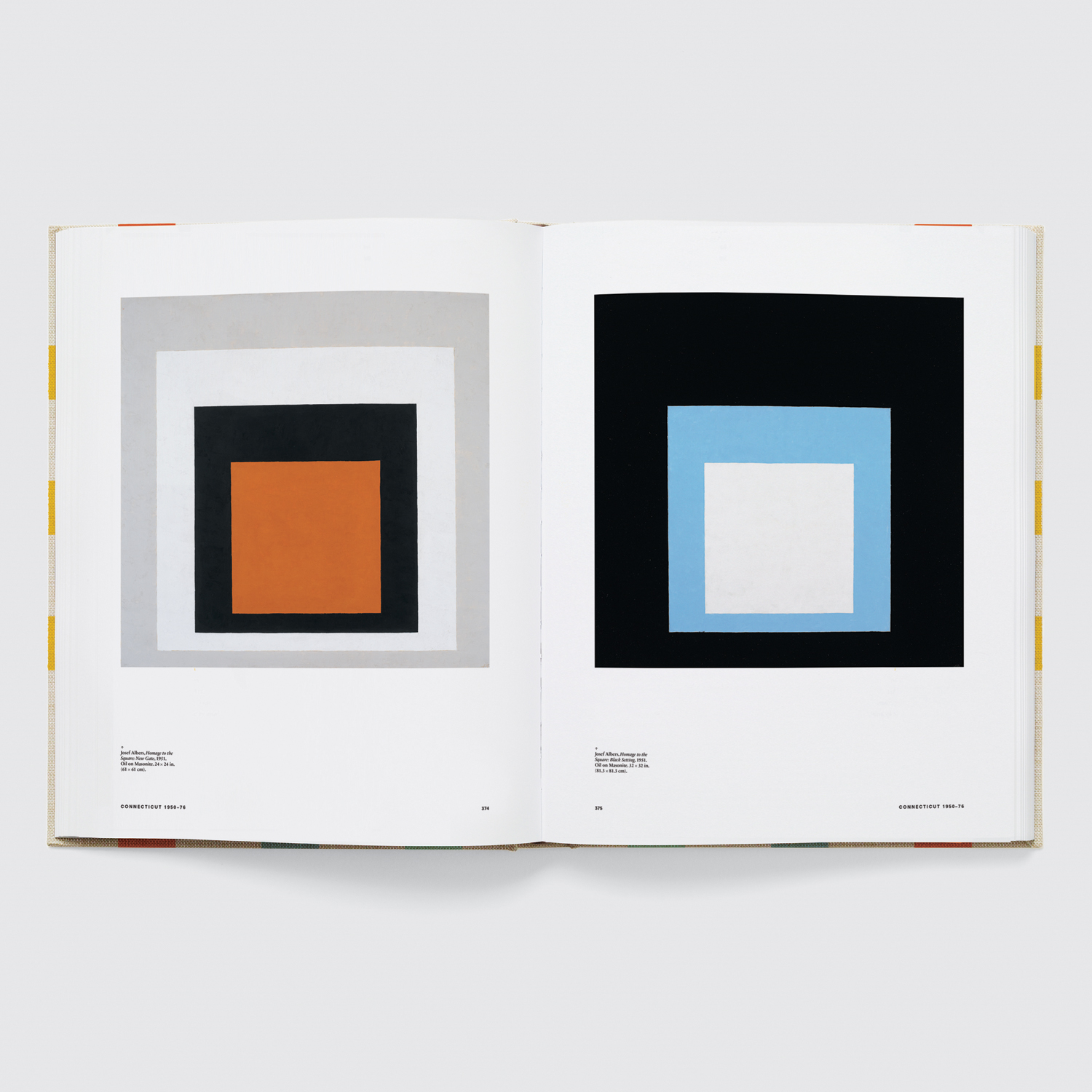

“The Alberses’ art, particularly what they would produce in the sixteen years at Black Mountain, is a perpetual journey, one turn always leading to another in what might seem like a different direction, but the spirits and values are entirely consistent,” writes Fox Weber. “The ethos and artistic standards Anni and Josef had developed side by side at the Bauhaus governed their innermost beings as well as their decisions on how to live and the nature of their art for the rest of their lives. They were impervious to trends. Fashion amused them at times—fashion in the sense of shifting modes of taste—but if they might get a kick out of Marilyn Monroe’s fringes or miniskirts, when Josef wrote about women’s dresses, it was generically. What interested the Alberses were lasting truths, not short-term fads.”

Despite mixing among the most rarefied of artistic milieus, in the richest country in the world, the Alberses did not change so much as deepen the way they worked, following a working practice they had established at the Bauhaus.

“Even at a juncture in their lives when so much else could have distracted them—the obligations inherent in establishing a new way of life in a new country, with hardly a cent to spare; the events taking place back in their homeland; the sense of losing their moorings—they in fact had an anchor that gave them an assurance, an abiding sense of joy, that not only withstood all the exigencies of their lives, but also provided a sense of richness on a daily basis,” writes Fox Weber.

“If some other refugees from war-torn Europe were struggling with the harsh realities of exile, the Alberses were rhapsodic, their reports filled with one rich discovery after another unfolding before their eyes.

To see further images from this period, and to gain a deeper understand of the couple’s incomparable art and incredible lives order a copy of Anni & Josef Albers here. To learn more about the fascinating life and incredible architecture of Philip Johnson get a copy of Philip Johnson A Visual Biography, here.