Phaidon's 15 Minute Art Lesson - Picasso and Cubism – by E. H. Gombrich

Read how primitivism and playfulness led to one of the most important artistic developments of the 20th century

Museums and galleries might be shuttered for Spring, and many education facilities have closed down, but that doesn’t mean you have to turn your back on high culture just yet. During the Coronavirus shut-down we're bringing you engaging, informative and thought-provoking extracts from our enviable back catalogue.

And when it comes to art history, few authors are more authoritative or thought-provoking as E. H. Gombrich, the man behind The Story of Art, the world’s best-selling work of art history. Within those pages, he covers everything from cave painting through to late modernism; and, in his account of Picasso and the Cubists, those two movements meet. This is how the young Spanish artist changed the way we look at the world.

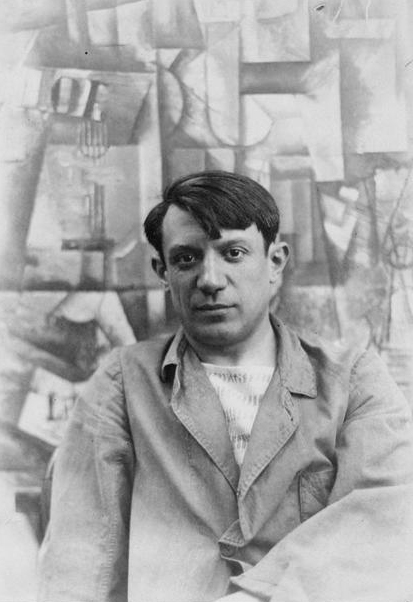

“Picasso was the son of a drawing master, and had been something of an infant prodigy in the Barcelona Art School,” writes Gombrich. “At the age of nineteen he had come to Paris, where he painted subjects that would have pleased the Expressionists: beggars, outcasts, strollers and circus people. But he evidently found no satisfaction in this, and began to study primitive art, to which Gauguin and perhaps also Matisse had drawn attention. We can imagine what he learned from these works: he learned how it is possible to build up an image of a face or an object out of a few very simple elements.

“This was something different from the simplification of the visual impression which the earlier artists had practised. They had reduced the forms of nature to a flat pattern. Perhaps there were means of avoiding that flatness, of building up the picture of simple objects and yet retaining a sense of solidity and depth? It was this problem which led Picasso back to the French painter, Paul Cézanne. In one of his letters to a young painter, Cézanne had advised him to look at nature in terms of spheres, cones and cylinders. He presumably meant that he should always keep these basic solid shapes in mind when organizing his pictures. But Picasso and his friends decided to take this advice literally. I suppose they reasoned somewhat like this: ‘We have long given up claiming that we represent things as they appear to our eyes. That was a willo’-the-wisp which it is useless to pursue.

We do not want to fix on the canvas the imaginary impression of a fleeting moment. Let us follow Cézanne’s example, and build up the picture of our motifs as solidly and enduringly as we can. Why not be consistent and accept the fact that our real aim is rather to construct something than to copy something? If we think of an object, let us say a violin, it does not appear before the eye of our mind as we would see it with our bodily eyes. We can, and in fact do, think of its various aspects at the same time. Some of them stand out so clearly that we feel that we can touch and handle them; other are somehow blurred. And yet this strange medley of images represents more of the “real” violin than any single snapshot or meticulous painting could ever contain.’

“Of course, there is one drawback in this method of building up the image of an object, of which the originators of Cubism were very well aware. It can be done only with more or less familiar forms. Those who look at the picture must know what a violin looks like to be able to relate the various fragments in the picture to each other. That is the reason why the Cubist painters usually chose familiar motifs – guitars, bottles, fruit-bowls, or occasionally a human figure – where we can easily pick our way through the paintings and understand the relationship of the various parts.

“Not all people enjoy this game, and there is no reason why they should. But there is every reason why they should not misunderstand the artist’s purpose. Critics considered it an insult to their intelligence to be expected to believe that a violin ‘looks like that’. But there never was any question of an insult. If anything, the artist paid them a compliment. He assumed that they knew what a violin was like, and that they did not come to his pictures to receive this elementary information. He invited them to share with him in this sophisticated game of building up the idea of a tangible solid object out of the few flat fragments on his canvas.

“We know that artists of all periods have tried to put forward their solution of the essential paradox of painting, which is that it represents depth on a surface. Cubism was an attempt not to gloss over this paradox but rather to exploit it for new effects. But while the Fauves had sacrificed the device of shading to the pleasure of colour, the Cubists took the opposite road: they renounced that pleasure and rather played their game of hide-and-seek with the traditional device of ‘formal’ modelling.

“Picasso never pretended that the methods of Cubism could replace all other ways of representing the visible world. On the contrary. He was ever ready to change his methods and to return once in a while from the boldest experiments in image-making to various traditional forms of art.

“No method and no technique satisfied him for long. At times he abandoned painting for handmade pottery. Maybe it was precisely his amazing facility in draughtsmanship, his technical virtuosity, which made Picasso long for the simple and uncomplicated. It must have given him a peculiar satisfaction to throw all his cunning and cleverness overboard and to make something with his own hands which recalls the works of peasants or children.

“Picasso himself denied that he was making experiments. He said he did not search, he found. He mocked at those who wanted to understand his art. ‘Everyone wants to understand art. Why not try to understand the song of a bird?’ Of course, he was right.”

For more on this, and almost all other aspects of human artisty, get The Story of Art by E. H. Gombrich here. We're delivering as usual during the Coronavirus crisis. And take a long look at all our other art books both new and old here.