How Rembrandt made his name

On the Dutch master’s birthday, we look at how, like Kanye and Madonna, he became a single-named star

Rembrandt van Rijn is the greatest painter of the Dutch Golden Age, so famous that we know him by just his first name. Yet while Rembrandt was very much a Dutch artist, his genius lay in reaching beyond his borders, while remaining steadfastly at home.

What do we mean? Well, as our new book Art = explains, the Dutch Golden Age was “a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the seventeenth century, in which Dutch trade and exploration, scientific advances, military successes, and artistic developments were among the most acclaimed in the West.

“Dutch Golden Age artists were leaders in the creation of still lifes, landscapes, and genre painting, the popularity of which was linked to Protestantism, the secularization of Dutch society, and a newly wealthy middle class.”

This point is picked up on by the great art historian Tancred Borenius in the introduction to our classic Rembrandt book. Borenius contrasts the culture of Dutch society, with the more regal, religiously minded atmosphere found in Belgium, just to the south.

“Belgium continued to acknowledge the sovereignty of the kings of Spain, while Holland achieved complete political independence,” he writes. “In Belgium, Catholicism remained the predominant form of religion, and this meant that, for painting, there was in the decoration of the churches a vast field for the cultivation of monumental design.

"Holland, on the other hand, embraced a form of Protestantism that was particularly opposed to the decoration of places of worship, and Dutch painters thus came to be shut off from one of the principal opportunities of developing a style of monumental design.”

And this wasn’t the only distinction. “Holland was by far the more democratic community of the two — a country where, as an English observer noted in 1609, if the immensely rich people were very few, the number of quite poor people was also very small; in Belgium, on the other hand, we find a much more unequal division both of political power and of wealth.

“Consequently, in Belgium, painters found plenty of work in the production of great decorative paintings of historical and mythological subjects, of hunting scenes and still-life pieces on a grand scale, for the palaces and châteaux of the aristocracy; while in Holland, painters were principally engaged in producing pictures for the much less grand homes of the well-to-do burghers, pictures generally of quite moderate dimensions, distinctly homely character portraits, scenes from passing life, landscapes, still-life pictures and the like.”

Into this setting, Rembrandt, the son of a well-off miller, thrived, leading a successful, domestic life within his homeland’s borders. Yet he didn’t limit himself to domestic influences.

“Rembrandt never went abroad,” explains Art =, “but he voraciously surveyed the work of northern European artists who had lived in Italy, including [early tutor] Pieter Lastman, the Utrecht painter Gerrit van Honthorst (Rembrandt’s main link to Caravaggio), Anthony van Dyck, and— mostly through prints—Adam Elsheimer and Peter Paul Rubens.”

This is a point that Borenius picks up on in his introductory essay, highlighting debts to Caravaggio, as well as works in Rembrandt’s personal art collection by Raphael and Michelangelo.

Of course, his great paintings remain well within the ascribed subject matter of the Dutch Golden Age. “A crucial aspect of Rembrandt’s development was his intense study of people, objects, and their surroundings ‘from life,’” the text in Art = goes on to reveal.

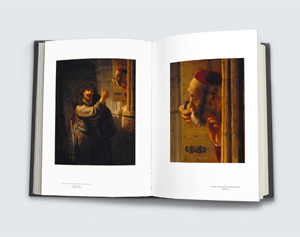

Yet, there are exotic ingredients too. We can see this masterly mix of Dutch influences and Italian art in many of Rembrandt’s self-portraits. Art = reproduces one from 1640, (above), which features his distinctly southern European signature.

“Rembrandt exudes confidence and urbanity in his Self-Portrait,” explains Art = , “modeled on courtly portraits by Raphael and Titian. These artists probably also inspired his Amsterdam signature, ‘Rembrandt’ minus the ‘van Rijn’.”

Before Kanye and Madonna, Rembrandt became an early example of the one-name art celebrity, thanks both to his homebody tendencies, but also thanks to his taste for the foreign and exotic.

For more on Rembrandt's place in art history, order a copy of Art =, a fresh and unconventional approach to exploring 6,000 years of art history through 800 masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Meanwhile, for a deeply, more leisurely look into Rembrandt's great works, consider a copy of our classic Rembrandt book.